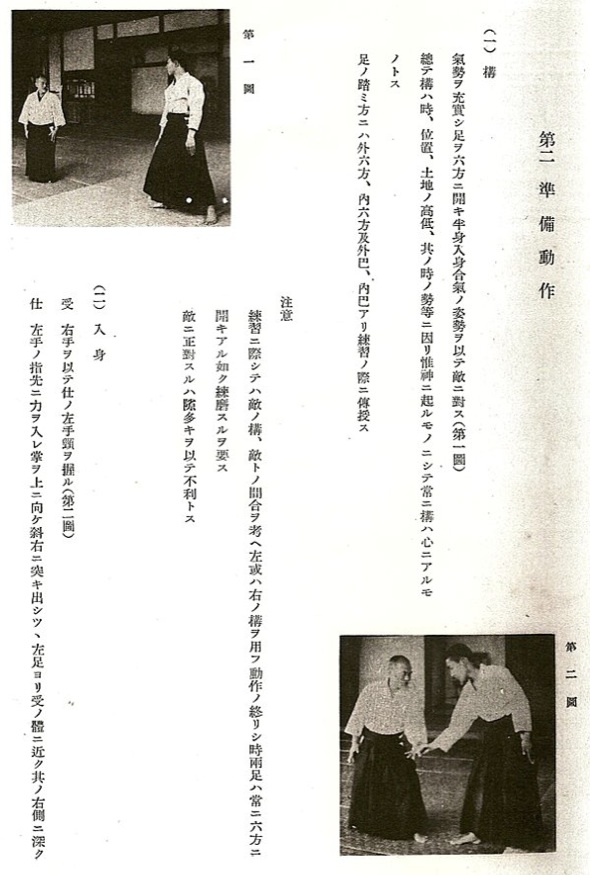

“Kamae” from the technical manual “Budo”

Morihei Ueshiba 1938

Why we don’t know how to stand up and walk.

Standing and walking – that’s pretty basic. It’s so basic that it’s really the first thing you learn in most budo, or even in life – if anybody can remember back that far.

Like everybody else, I received basic instructions in how to stand when I started Aikido – point the front foot forward and the back foot out at an angle. Some places break that down into a more detailed description, but that’s usually the gist of it.

Pretty easy right? Anybody can do it – which may be the problem. If anybody can do it, and you’re doing essentially the same thing that you’ve always done…why are you spending all that time on the mat?

“Budo” is a pre-war technical manual published in 1938 by Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba. It was originally created for Prince Kaya Tsunenori, member of a collateral branch of the imperial family. Kayanomiya would eventually become Superintendant of the Army Toyama School – where Morihei Ueshiba would act as an instructor before the war.

“Budo” remains the largest and most organized collection of technique from the pre-war period, and an English edition (“Budo: Teachings of the Founder of Aikido“), translated by John Stevens, was published in 1991.

A separate edition, the “Takemusu Aikido Special Edition”, translated by Sonoko Tanaka and Stanley A. Pranin, was published in 1999 (“Budo: Commentary on the 1938 Training Manual of Morihei Ueshiba“). This edition is composed of some excerpts from the Japanese text, along with a commentary by Morihiro Saito, in both English and Japanese.

Here is the original Japanese text, followed first by my English translation, and then by the English translation by John Stevens.

The original Japanese text:

第二 準備動作

(一)構

氣勢ニヲ充實シ足ヲ六方ニ開キ半身入身合氣ノ姿勢ヲ以テ敵ニ對ス(第一圖)

總テ構ハ時、位置、土地ノ高低、其ノ時ノ勢等ニ因リ惟神ニ起ルモノニシテ常ニ構ハ心ニアルモノトス

足ノ踏ミ方ニハ外六方、内六方及外巴、内巴アリ練習ノ際ニ傅授ス

注意

練習ノ際シテハ敵ノ構、敵トノ間合ヲ考ヘ左或ハ右ノ構ヲ用フ動作ノ終リシ時兩足ハ常ニ六方ニ開キアル如ク練磨スル要ス

敵ニ正對スルハ隙多キヲ以テ不利トス

My English translation:

Section 2: Preparatory Movements

(1) Kamae

Fill yourself with Ki power, open your legs in six directions and face the enemy in the hanmi irimi posture of Aiki (see Figure 1).

When assuming any stance, align yourself with the principles of the Kami according to your position, the level of the terrain and your spirit at that time, and always keep this stance in your heart.

In footwork there is an external six directions and an internal six directions as well as an outer spiral and an internal spiral, this will be taught in practice.

Caution:

Concerning the stance of the enemy in training.

Be mindful of the distance between you and the enemy and assume a left or right stance. At the end of each movement always open both legs in six directions, it is necessary to train this.

If you face directly towards the enemy there will be many openings and you will be at a disadvantage.

The standard translation, from “Budo: Teachings of the Founder of Aikido” (translated by John Stevens):

2. Basic Movements

(1) Stance

Fill yourself with ki, assume a hanmi stance with your feet apart opened at a sixty-degree angle, and face your opponent with a flexible aiki posture (1).

The exact stance depends upon time, place, and terrain; further, it must arise in accordance with divine principles. A good stance reflects a proper frame of mind.

Both the front foot and the back foot should be open at a sixty-degree angle. The reason for this will become clear in practice.

Note: During practice be ever mindful of your opponent’s stance and his relative distance; assume, accordingly, a left or right stance. When the movement ends, it is essential that your feet should always be open at a sixty-degree angle. If you face your opponent full of openings you will be at a great disadvantage.

Right away you can see some differences. This is normal – no two translations, especially from a language like Japanese, are going to be absolutely the same. Some things are differences in expression, some in how the translator chose or was able to interpret the work, some are just mistakes.

Some phrases in Japanese cannot be translated directly into English without losing their original meaning – and the same for English phrases into Japanese.

Looking at the passages above, there are some minor differences and some not so minor differences.

The title of the section, for example, I translated as “Preparatory Movements”, instead of “Basic Movements”. Mine is a more literal translation of the actual Japanese, but if you compare the two you’ll see that, in the end, the difference is really not very important. Who cares? Not me.

There are some other differences, however, further down.

I translated the first sentence of the passage as:

Fill yourself with Ki power, open your legs in six directions and face the enemy in the hanmi irimi posture of Aiki (see Figure 1).

The John Stevens translation is:

Fill yourself with ki, assume a hanmi stance with your feet apart opened at a sixty-degree angle, and face your opponent with a flexible aiki posture (1).

There are are two big problems here.

First, the word “flexible” appears to have been inserted in the place of “irimi”. This seems a little odd, since most Aikido students ought to be familiar with at least the basic concept of irimi – and I’m not sure exactly how Ueshiba was trying to express “flexibility” with the word in this case (I can imagine some possibilities – but it involves a fair amount of speculation).

Secondly, and probably more importantly, the phrase “open your legs in six directions” is replaced, in the Stevens translation, by “feet apart opened at a sixty-degree angle”, which is completely different than the original Japanese text – which reads as I have represented above.

Does it matter?

Well, let’s look at “roppo”, or “six directions”.

There is another, partial translation of “Budo”, by Sonoko Tanaka and Stanley A. Pranin published as “Budo: Commentary on the 1938 Training Manual of Morihei Ueshiba”. In that text they note that the original Japanese text actually says “six directions”.

Problem solved?

Maybe not, because the assertion given there is that “six directions” is basically another way to say “hanmi”, which was not in common usage at that time.

Now is the problem solved?

Again, maybe not. Oddly enough, the word “hanmi” appears in the first sentence of the original Japanese. If the word “hanmi” was not in common usage at the time then why would Morihei Ueshiba use both that word and “six directions” in the same sentence?

What, then, could “six directions” mean?

Interestingly, “six directions” is a common term in Chinese internal martial arts. Take a look at Liu Mian Mo Li (六面摸力) in Yiquan, for a good example – a force balanced through your body in six directions. In this case we’re talking about basic stability in all directions – something that makes all kinds of sense in terms of standing up and walking in a martial situation. This is fairly common in Chinese internal martial arts – for example, here is a good example of six-direction force in Xingyi Quan.

One more interesting note – in “Budo: Commentary on the 1938 Training Manual of Morihei Ueshiba” they also note that “step from a roppo stance” is used in Kabuki as well. What is not noted, however, is that some traditional Noh schools also use this phrase – in the sense of universal stability and balanced forces that is shared with Chinese internal martial arts.

Now, how about the line:

In footwork there is an external six directions and an internal six directions as well as an outer spiral and an internal spiral, this will be taught in practice.

In the standard translation by John Stevens this line is given as:

Both the front foot and the back foot should be open at a sixty-degree angle. The reason for this will become clear in practice.

Again, we see that the phrase “six directions” has been replaced “sixty-degree angle”, although that is totally at variance with the original Japanese.

Further, the phrase “an outer spiral and an internal spiral” has been completely omitted from the English translation in “Budo: Teachings of the Founder of Aikido”. These spirals are also omitted from “Budo: Commentary on the 1938 Training Manual of Morihei Ueshiba”.

So…does that section of the description really matter?

Well, I suppose that you could argue that, for the sake of historical accuracy alone, it is important to provide as complete a translation as possible.

But there’s more.

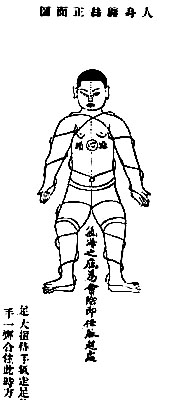

Inner and outer spirals through the legs and body are also commonly described in Chinese internal martial arts (there may be a theme developing here!). Here is a diagram and excerpt of text from “Illustrated Explanations of Chen Family Taijiquan” by Chen Xin, the emphasis of the underlined section is mine.

Coiling power (Chan Jin) is all over the body. Putting it most simply, there is coiling inward (Li Chan) and coiling outward (Wai Chan), which both appear once (one) moves. There is one (kind of coiling) when left hand is in front and right hand is behind; (or when) right hand is in front and left hand is behind; this one closes (He) (the hands) with one conforming (Shun) (movement). There is also one (coiling) that closes the inside of the left (side of the body) and the back of the right (side of the body), and another which uses the through-the-back power (Fanbei Jin) and closes towards the back. All of them should be moved naturally according to the (specific) postures.

Once Qi of the hand moves to the back of the foot, then big toe simultaneously closes with the hand and only at this moment (one can) step firmly.

Illustrated Explanations of Chen Family Taijiquan

Ever hear of it? I hadn’t – because it doesn’t appear in any of the published English translations.

But what about the Japanese editions?

Well…there are none.

Hard as it is to believe, there has never been a commercial re-publication of the text of “Budo” in Japanese. The only people in Japan who have read “Budo” are those that have gotten hold of the original publication or a homemade copy. The very existence of “Budo” itself was known only to a few people until it was rediscovered by Stan Pranin through Zenzaburo Akazawa (a pre-war student of Ueshiba) around 1979. Even Morihiro Saito, who, it could be argued, spent more time alone with Ueshiba after the war than anybody else, was astonished to learn of this text!

So…just as in the blog post “Kiichi Hogen and the Secret of Aikido“, we once again have Morihei Ueshiba citing a basic concept from the Chinese martial arts as being central to Aikido.

We also have a clear example of the problem with that exists in the transmission of basic information in Aikido – from both the English and Japanese sides.

What don’t we know, and what don’t we know we don’t know?

And why aren’t we examining it more closely?

Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI

Leave a Reply