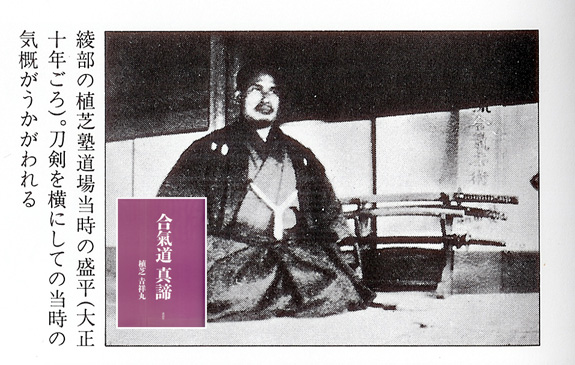

Morihei Ueshiba in Ayabe, 1922

Morihei Ueshiba in Ayabe, 1922

in front of a placard reading “Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu”

In 1922 Sokaku Takeda moved to the Omoto compound in Ayabe to live with Morihei Ueshiba and give him intensive instruction for five months. Ueshiba first met Takeda in 1915 at the Hisada Inn in Engaru, Hokkaido, and trained intensively with him for a number of years before moving to Ayabe. Sokaku Takeda’s son Tokimune once commented:

He trained extensively and was enthusiastic. He was Sokaku’s favorite student.

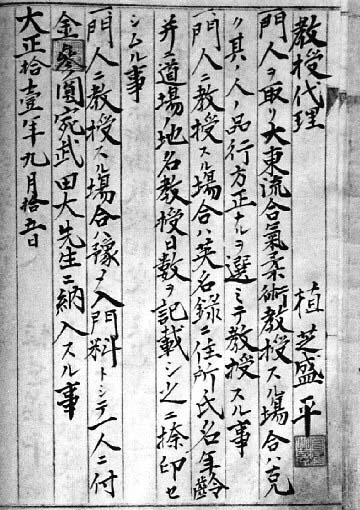

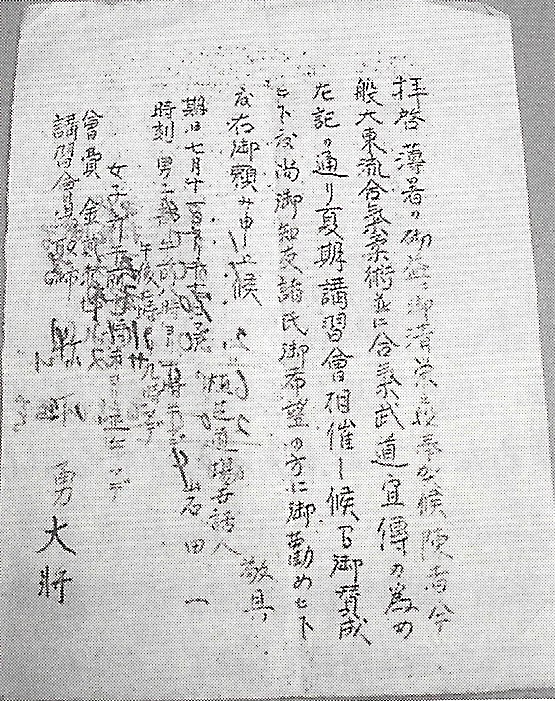

In 1922, at the conclusion of his stay in Ayabe, Sokaku Takeda awarded a Kyoju Dairi (assistant instructor) certificate in Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu to Morihei Ueshiba, making him a certified instructor in the art.

Morihei Ueshiba’s Kyoju Dairi in Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu

Morihei Ueshiba’s Kyoju Dairi in Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu

This relationship between teacher and student, Sokaku Takeda and Morihei Ueshiba, would last for more then twenty years:

Let me begin by stating categorically that the major technical influence on the development of aikido is Daito-ryu jujutsu. This art, which is said to be the continuation of a martial tradition of the Aizu Clan dating back several hundred years, was propagated in many areas of Japan during the Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa periods by the famous martial artist, Sokaku Takeda. Known equally for his martial prowess and severity of character, Takeda had used his skills in life-and-death encounters on more than one occasion. Takeda was fifty-four years old when Morihei Ueshiba first met him at the Hisada Inn in Engaru, Hokkaido in late February 1915. This encounter marked the beginning of a long, stormy yet ultimately productive association between the two, which lasted for more than twenty years.

Aikido Journal Editor Stan Pranin – “Morihei Ueshiba and Sokaku Takeda“

But what happened next?

Kisshomaru Ueshiba and Post-war Aikido

On October 27, 1985 in Sendai, I attended a lecture on the history of aikido given by Second Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba. During his talk Kisshomaru Sensei made the following remark: “The Founder only studied Daito-ryu for three weeks or so.” My jaw dropped in disbelief when perhaps the most knowledgeable person in the world on the subject of aikido history made such a patently false statement!

Aikido Journal Editor Stan Pranin – “Beware the big lie!“

The picture of Morihei Ueshiba at the beginning of this article was taken in 1922 after receiving his Kyoju Dairi certification from Sokaku Takeda, which marks the beginning of his teaching career in the martial arts, and as an instructor in Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu under the authority of Sokaku Takeda.

However, there is a narrative in the modern Aikido world, one that is encouraged by the Aikikai, in which Aikido is the original and unique creation of Morihei Ueshiba. This narrative stipulates that Aikido is something that he created after studying a number of martial arts, and that it represented a radical phase change from his pre-war practices, and that it represented a new and original spiritual dimension.

But is that really the case?

To begin with, this narrative is complicated by Kisshomaru Ueshiba’s representation that the key spiritual revelation, that of “the great spirit of mutual loving protection” (万有愛護の大精神) – occurred in 1925. Rather than after occurring after the war, this was towards the very start of his career as an instructor of Daito-ryu.

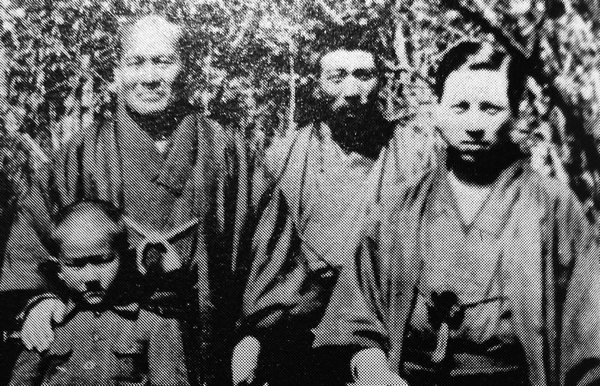

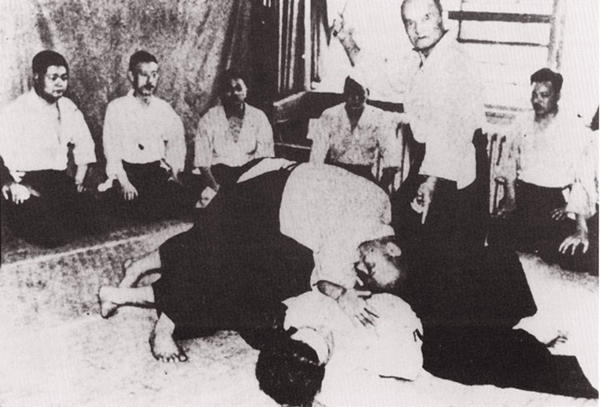

Kisshomaru Ueshiba with his father at Ueshiba Juku, Ayabe in 1925

Kisshomaru Ueshiba with his father at Ueshiba Juku, Ayabe in 1925

Going back from there to Daito-ryu itself we see the roots of Morihei Ueshiba’s philosophy…already in existence.

Masao Hayashima – a direct student of Sokaku Takeda

“Aiki-jutsu is said to be the Budo of Harmony”.

In addition to Masao Hayashima (above) we also have Morihei Ueshiba’s contemporary, and a fellow student of Sokaku Takeda, Yukiyoshi Sagawa and “Aiki Budo is the Way of Human Development“.

Then, we have Sokaku Takeda’s son Tokimune Takeda discussing his father’s instruction:

“The essential principles of Daito-ryu are Love and Harmony”

“The goal of spreading Daito-ryu is ‘Harmony and Love’, keeping this spirit is what preserves and realizes social justice. This was Sokaku Sensei’s dying wish”

But these concepts can be tracked all through the Japanese martial traditions, they are far from unique to either Morihei Ueshiba or Daito-ryu.

- 「武ハ弋止ノ義何ゾ好テ以テ殺戮センヤ」 “Bu is the abandoning of violence. One must not find pleasure in slaughter.”, Katayama-ryu Densho – 1647

- 「我モ勝ズ人モ勝ズ相得テ共ニ治ル」 “Oneself and another who cannot win are both unable to attain victory, so both mutually return to a state of peace.”, Katayama-ryu Densho – 1647

- 「兵法は平法なり」 “The methods of war are the methods of peace”, Iizasa Ienao of Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto-ryu – 1387-1488

This argument was expressed by Professor Karl Friday, a Japanese historian and a student of the Japanese martial traditions (having received full transmission in Kashima Shin-ryu) in this excerpt from an interview in 2009:

The conventional wisdom on Japanese martial art (ryūha bugei) ties its evolution closely to the history of warfare. It starts from the premise that systems and schools of martial art originally developed as tools for passing on workaday battlefield skills, in response to intensified demand for skilled fighting men spawned by the onset of the Sengoku age. Warriors hoping to survive and prosper on late medieval battlefields began to seek instruction from talented veterans, who in turn began to codify their knowledge and methodize its study. Thus bugei ryūha emerged more-or-less directly from the exigencies of medieval warfare. But-so goes the tale-the two-and-a-half-century Pax Tokugawa that began in 1600 brought fundamental changes to the practice of martial art. Instruction became professionalized, and in some cases, commercialized; training periods became longer, curricula were formalized; and elaborate systems of student ranks developed. Most significantly, however, the motives and goals underlying bugei practice were recast. Samurai, who no longer expected to spend time on the battlefield, sought and found a more relevant rationale for studying martial art, approaching it not simply as a means to proficiency in combat, as their ancestors had, but as a means to spiritual cultivation of the self.

This is basically the story I summarized in my Legacies of the Sword book. It begins from the logical assumption that ryūha bugei originated as an instrument for ordinary military training, and evolved from there into budō, a means to broader self-development and self-realization. But there are some problems with this picture that become clear if you juxtapose it against recent research on medieval warfare.

It‘s clear, first of all, that ryūha bugei couldn’t have accounted for more than a tiny portion of sixteenth-century military training. There were at most a few dozen ryūha around during the 16th century, but armies of that era regularly mobilized tens of thousands of men. In order for even a fraction of sengoku warriors to have learned their craft through one or more ryūha, each and every ryūha of the period would need to have trained at least several hundred students a year. Ryūha bugei must, therefore, have been a specialized activity, pursued by only a minute percentage of Sengoku warriors.

An even bigger issue, however, is the applicability of the skills that late medieval bugeisha concentrated on developing to sixteenth-century warfare. For one thing, strategy and tactics were shifting, from the 15th century onward-precisely the period in which bugei ryūha began to appear-from reliance on individual warriors and small group tactics to disciplined group tactical maneuver. Which means that ryūha bugei, focusing on developing prowess in personal combat, emerged and flourished in almost inverse proportion to the value of skilled individual fighters on the battlefield.

All of the recent scholarship on late medieval warfare, moreover, argues that swords never became a key battlefield armament in Japan-that they were, rather, supplementary weapons, analogous to the sidearms worn by modern soldiers. While swords were carried in combat, they were used far more often in street fights, robberies, assassinations and other (off-battlefield) civil disturbances. Missile weapons-arrows, rocks, and later bullets-dominated battles, throughout the medieval period.

On the other hand, almost all of the ryūha that date back to the sengoku period or earlier claim that swordsmanship played a central role in their training, right from the start. Tsukahara Bokuden, Kamiizumi Ise-no-kami, Iizasa Chōisai, Itō Ittōsai, Yagyū Muneyoshi, Miyamoto Musashi and other founders of martial art schools were (are) all best known for their prowess as swordsmen.

Initially, I wondered if the place of swordsmanship in medieval martial art represented a major piece of counter-evidence to the new consensus on late medieval warfare. After all, if bugei ryūha started out as systems to train warriors for the battlefield, and made swordsmanship central to their arts, wouldn’t that suggest that swords were more important to medieval warfare than the new scholarship would have us believe?

After wrestling with that question for quite a while, it finally struck me that the problem might lie in the first premise of this argument. All of the questions that were bothering me (why did bugei ryūha emerge at a time when generalship was rapidly coming to overshadow personal martial skills as the decisive element in battle, and the key to a successful military career? Why were there so few ryūha around during the Sengoku era, and why did they proliferate so rapidly during the early Tokugawa period, after the age of wars had passed? And why was swordsmanship so prominent in even the earliest bugei ryūha?) become much easier to answer if you just set aside the premise that bugei ryūha originated as instruments for teaching the workaday techniques of the battlefield. And the truth of the matter is that there’s little basis for that hoary assumption, beyond the fact that war was endemic in Japan when the first martial art schools appeared. The received wisdom rests, in other words, on what amounts to a post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy.

It seems likely, then, that ryūha bugei and the pedagogical devices associated with it aimed from the start at conveying more abstract ideals of self-development and enlightenment. That is, that ryūha bugei was an abstraction of military science, not merely an application of it. It fostered character traits and tactical acumen that made those who practiced it better warriors, but its goals and ideals were more akin to those of liberal education than vocational training. In other words, bugeisha, even during the Sengoku era, had more in common with Olympic marksmanship competitors-training with specialized weapons to develop esoteric levels of skill under particularized conditions-than with Marine riflemen. They also had as much-perhaps more-in common with Tokugawa era and modern martial artists than with the ordinary warriors of their own day.

Basically, I’m arguing that there was no fundamental shift of purpose in martial art education between the late sixteenth and mid-seventeenth centuries. Tokugawa era budō represented not a metamorphosis of late medieval martial art, but the maturation of it. Ryūha bugei itself constituted a new phenomenon-a derivative, not a linear improvement, of earlier, more prosaic military training.

(For the full argument, see my “Off the Warpath” piece, in Alex Bennett’s Budo Perspectives [Auckland, New Zealand: Kendo World Publications, 2005], 249-68.)

Far from being new and original, or unique to Morihei Ueshiba and modern Aikido, we see that the concept of a martial tradition for spiritual and personal development is something that is very old, and endemic to many arts.

Does that matter?

Certainly, Morihei Ueshiba was a spiritual person, and believed that he practiced and taught an art that enabled personal and spiritual development.

That the concepts he expressed were neither unique nor original doesn’t take away from that message.

In my opinion it is time to abandon the conceit of spiritual exceptionalism and uniqueness that often exists in modern Aikido, in the long run it is only destructive to the art as a whole.

Morihei Ueshiba and Daito-ryu

Now, what about Morihei Ueshiba’s involvement with Daito-ryu and Sokaku Takeda?

The base description on the Aikikai website reads:

Aikido is a modern Martial Art created by the Founder, Morihei Ueshiba.

A more detailed description contains the same narrative:

Aikido is a Japanese Martial Art created during the 1920s by Morihei Ueshiba (1883~1969), an expert who reached the highest level of mastery in the classical Japanese Martial Arts.

Neither contains any mention of Sokaku Takeda or Daito-ryu, but Takeda is mentioned once (and only once) on the biographical timeline of Morihei Ueshiba’s life:

The Founder meets Mr. Sokaku Takeda, the originator of Daito-ryu Jujutsu, at the Hisada Ryokan (inn) in Engaru, and asks for instruction.

And that’s it…

Similarly, in Kisshomaru Ueshiba’s books “The Spirit of Aikido” and “The Art of Aikido” there is virtually no mention of Daito-ryu in either one. Neither of them are historical works, but neither of them make any real mention of the only art that Morihei Ueshiba was ever licensed to teach, the only art (outside of his own) in which he ever issued certificates or licences.

In the more recent work, “Best Aikido“, written by Kisshomaru Ueshiba and Moriteru Ueshiba, there is a short mention of Daito-ryu as one of the many arts that Morihei Ueshiba studied, but no mention is made of the relative depth of study of those arts – the section entirely fails to note the fact that, with the exception of Daito-ryu, all of those arts were studied for very brief periods of time.

AW: O-sensei also reportedly studied a lot of other koryu arts outside of Daito-ryu.

SP: I would say that that’s not true.

If you look at it historically, he went up to Tokyo in 1901 and spent about a year there. During this stay in Tokyo when he was training to become a merchant, he did a little bit of Tenjin Shinyo-ryu jujutsu. It was probably a “machi” dojo, in other words a small dojo in the Asakusa area of Tokyo. He would go there at night, but it was probably about three or four months total since he got very ill with beriberi and had to leave Tokyo and return to Tanabe. He was doing it while working very hard during the day and it was a very brief period of only a few months. It would be difficult to imagine that that had a strong, technical influence.

By the same token when he was in the army, he also began studying Yagyu-ryu jujutsu. There are some questions about what the actual name of the art was. O-sensei referred to it as Yagyu-ryu jujutsu, while [Kisshomaru Ueshiba] Doshu did some research and said it was Goto-ha Yagyu Shingan-ryu or similar name.

He was in the army at the time and also was sent to Manchuria for a part of the time. It was hard for me to imagine him going regularly while being in the army, so I don’t know if his training was on the weekends or what. He apparently was enthusiastic about his training but there just weren’t the circumstances to allow a detailed study.

He did, however, continue to study a little bit of Yagyu-ryu after he got out of the army, but he was in Tanabe which was a couple of hundred miles away and he had to go up by ferry! Again, maybe he went up three, four, or a half a dozen times, but it wasn’t the sort of thing of an intensive study with someone year after year.

Now, he did have a makimono (scroll) as well — however, it bears no seal. One can only speculate what that meant. Sometimes what happens is that a person would be told to prepare a makimono or have someone prepare it and, for whatever circumstance or reason, the teacher never gets around to signing it. Therefore, the scroll cannot be considered official.

So, it would appear that he did study this Yagyu-ryu form more than the Tenjin Shinyo-ryu jujutsu, but probably at the most he did a year or two.

The other art that he studied, but again not in very much depth, would have been judo. The first description of the teacher who was sent down from the Kodokan to Tanabe by O-sensei’s father to teach Morihei and various relatives and friends gave the impression that this judo teacher was somewhat of an expert. It turns out he was 17 years old. I met his wife back in the 1980s and she told me this directly. He could have been a shodan, maximum. Also, O-sensei was involved with other things in this transition phase of his life trying to figure out what he was going to be doing as a career. One of the reasons, according to Doshu, that this judo person was brought in was to help him focus and channel his energies. But O-sensei ended up going to Hokkaido.

So, you have this very brief stint in Tenjin Shinyo Ryu, some training in Yagyu Ryu jujutsu while in the army, a smattering of judo, and then Daito-ryu. That’s it. The impression that he studied many different arts other than Daito-ryu and mastered them is completely false.

Aikiweb Interview with Stan Pranin – August, 2000

Now, let’s go back to the 1922 photo at the top of this article. In that photo Morihei Ueshiba is clearly sitting in front of a placard reading “Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu”.

Unfortunately, the Aikikai tinkered with the photo a bit at various times and in various publications – most likely in order to support the public narrative being promoted after the war.

Aikido Shimbun, issue 2 – May 1959

Aikido Shimbun, issue 2 – May 1959

original scan by Stan Pranin

The second issue of the Aikikai Foundation’s newsletter the “Aikido Shimbun” (pictured above) featured a copy of the 1922 photo from Ayabe – with the placard reading “Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu” carefully edited out. Additionally, there is no mention, at all, of Daito-ryu, or the context of the photo, in the text of the article.

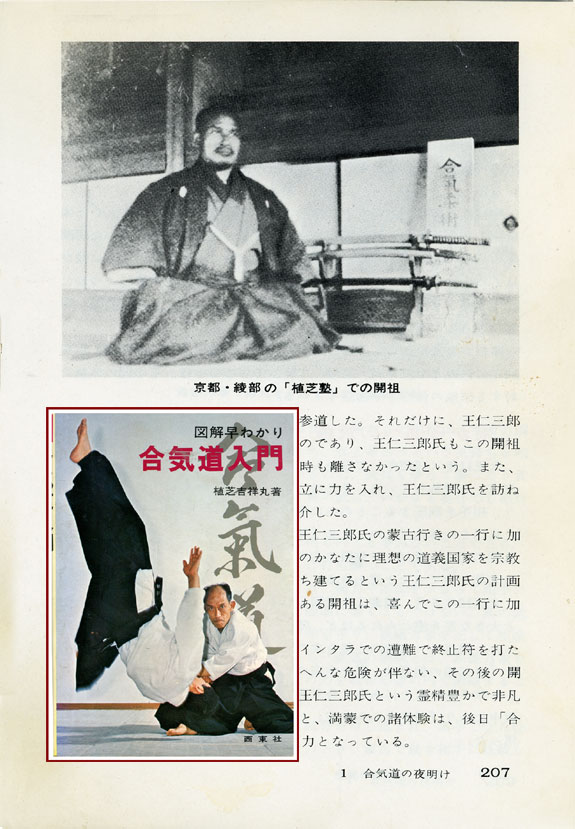

“Aikido Nymon,” by Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1975

“Aikido Nymon,” by Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1975

original scan by Stan Pranin

In this iteration, from a book published by Ni-Dai Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba in 1975, the characters for “Daito-ryu” have been edited out, leaving only the words “Aiki-jujutsu”.

“Aikido Shintei” by Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1986

“Aikido Shintei” by Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1986

In this photo, from a 1986 publication called “Aikido Shintei”, the characters for “Daito-ryu” are also edited out – but very poorly, leaving part of the “ryu” character intact.

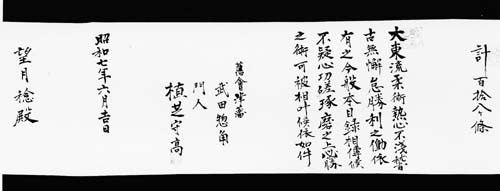

Invitation to summer training with Morihei Ueshiba

Invitation to summer training with Morihei Ueshiba

in Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu and Aiki-budo, 1931

Morihei Ueshiba and Daito-ryu – Continuity

in 1933 Morihei Ueshiba published a Daito-ryu technical instruction manual, Aikijujutsu Densho. which was stamped “Aikijujutsu”, and was distributed to students receiving certificates in Daito-ryu as a kind of transmission document. Jump ahead – he re-published the same manual, with the same techniques and explanations (minus the pre-war imperial language) in 1954 as Aikido Maki-no-ichi. Morihei Ueshiba used this manual as a textbook when teaching in the 1950’s.

Then in 1938 Morihei Ueshiba published the technical manual “Budo“. This book, re-discovered by Aikido Journal editor Stan Pranin, contais techniques that Morihiro Saito claimed were identical to the techniques taught by Morihei Ueshiba’s at Morihei Ueshiba’s home in Iwama, where he lived from 1942 until near the time of his death.

One day in July 1981, I was conducting an interview with Zenzaburo Akazawa, a prewar uchi deshi of Morihei Ueshiba from the Kobukan Dojo period. Mr. Akazawa proceeded to show me a technical manual published in 1938 titled Budo which I had never seen before. It contained photos of some fifty techniques demonstrated by the founder himself. As I slowly turned the pages of the manual, I was amazed to see in the photos that the execution of several basics techniques such as ikkyo, iriminage and shihonage were virtually identical to what I had learned in Iwama under Saito Sensei. Here was the founder himself demonstrating what I had up until then regarded as “Iwama-style” techniques. Mr. Akazawa, who lives only a few blocks away from the Iwama Dojo, kindly lent me the book and I hurried to show it to Saito Sensei.

I’ll always remember the scene as I called at Sensei’s door to share with him my new discovery. To my surprise, he had never seen or heard mention of the book before. He put on his reading glasses and leafed through the manual, his eyes scanning the technical sequences intently. I felt compelled then and there to apologize to him for having ever doubted his assertion that he was making every effort to faithfully preserve the founder’s techniques. Saito Sensei laughed and, obviously with great pleasure, bellowed, “See, Pranin, I told you so!” From that time on up through the end of his life, Saito Sensei always had along his copy of Budo in the Iwama Dojo and on his travels to use as proof to show that a particular technique originated in the founder’s teachings.

Aikido Journal editor Stan Pranin – “Remembering Morihiro Saito Sensei“

Moving on to 1940, Takuma Hisa – one of the only people to have received Menkyo Kaiden (“certificate of complete transmission”, showing that one has mastered the totality of a martial system) in Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu directly from Sokaku Takeda, published “Kannagara no Budo, Daito-ryu Aiki Budo Hiden“. This manual on Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu is almost an exact copy, in both technical explanation and the illustrated techniques, of the “Aikijujutsu Densho” manual published by Morihei Ueshiba in 1933…the manual that was used as a textbook for post-war students in the 1950’s as “Aikido Maki-no-Ichi”.

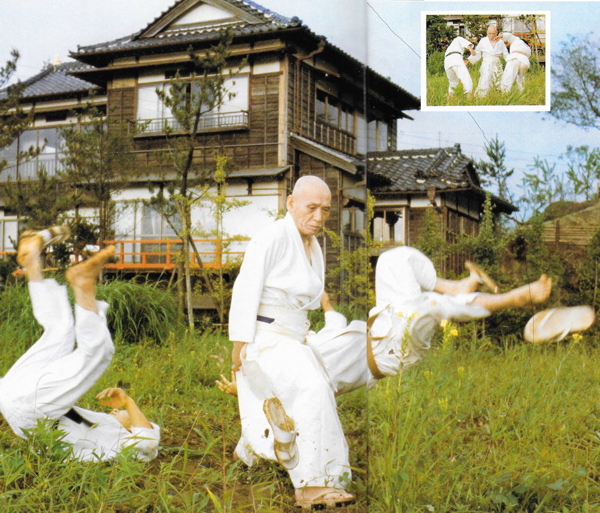

Sokaku Takeda at the Asahi Shimbun Dojo in Osaka – 1936

Sokaku Takeda at the Asahi Shimbun Dojo in Osaka – 1936

Takuma Hisa is also significant in that he was one of the few people who had a chance to directly compare Sokaku Takeda and Morihei Ueshiba in depth over an extended period of time:

Takeda’s instruction gave Hisa the chance to compare the techniques that he had been taught for the previous three years (1933-1936) by Ueshiba with those taught by Takeda. His conclusion was that they were the same—meaning that Ueshiba had not by that time significantly modified or evolved what he had been taught by Takeda. In later years, Hisa was adamant about Ueshiba’s and Takeda’s techniques being identical. He stated this clearly at a round table talk, “When Tomiki came to Osaka to teach aiki-bujutsu to the Asahi people, the techniques that both master Ueshiba and Takeda taught were the same. Definitely the same. Master Ueshiba should say that he was taught them by master Takeda. He should say that it was Daitoryu. But he never said that. Mr. Tomiki (who also traveled from Tokyo to Osaka to teach Ueshiba’s system at the Asahi dojo) knows this, doesn’t he. But Ueshiba never said it.” And Tomiki answered, “Definitely not. ‘I [Ueshiba] established everything…[smiling mysteriously]’. However old martial artists would often do that way.” [Shishida (Ed.), 1982, p.1]

“The Process of Forming Aikido and Japanese Imperial Navy Admiral Isamu Takeshita: Through the analysis of Takeshita’s diary from 1925 to 1931”

– Fumiaki Shishida (Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan)

Both Sokaku Takeda and Morihei Ueshiba kept a registry of their students. When one became a student their name would be entered into the book and the student would attach their seal. Mr. Kimura speaks a little about the registry, which he signed in 1942 in “Mr. Kimura’s Aikido Memories, Part 1“.

Mamoru Okada also remembers signing this registry – in this instance he signed the registry in 1949, after the war.

Hiroshi Isoyama also testifies that he signed this registry – again in 1949, after the war. Further, his testimony confirms that the registry was titled “Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu”:

And the title on my registration paper is “Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu registry”. This is what I signed. At the top of the students’ registry, there are also the names of people such as the Admiral Takeshita Isamu.

“Interview with Isoyama Hiroshi Shihan, the master of the Iwama Dojo“

That is to say – Morihei Ueshiba was enrolling people as students of Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu as late as 1949.

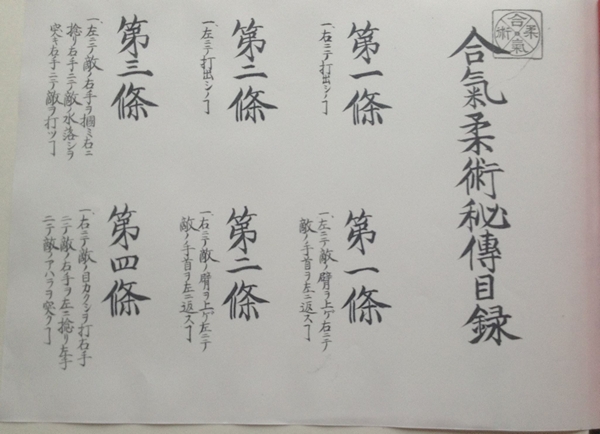

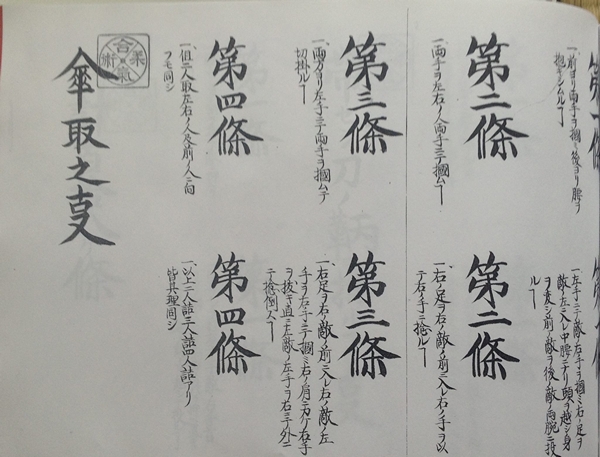

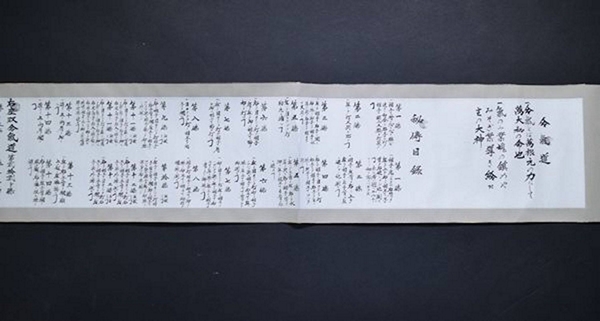

Here are some photos of a Hiden Mokuroku scroll (thanks to Scott Burke for the photos) – the “catalog of secret teachings” that composes the first scroll in the Daito-ryu curriculum. This scroll was issued by Morihei (then using the name Moritaka) Ueshiba in 1925:

“Aiki-jujutsu Hiden Mokuroku”, 1925

“Aiki-jujutsu Hiden Mokuroku”, 1925

The Aiki-jujutsu seal in the upper right hand corner is similar (but slightly different in shape) to the seal that appears in Morihei Ueshiba’s 1933 technical manual Aikijujutsu Densho – AKA Budo Renshu.

Here’s is another section of the same 1925 scroll:

Aiki-jujutsu umbrella techniques 1925

This section of the scroll covers techniques with an umbrella and is also stamped “Aiki-jujutsu”.

Hiden Mokuroku 118 Techniques

A continuation of the scroll – on the left is states that this scroll contains 118 techniques. The basic 118 techniques of the first scroll of Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu.

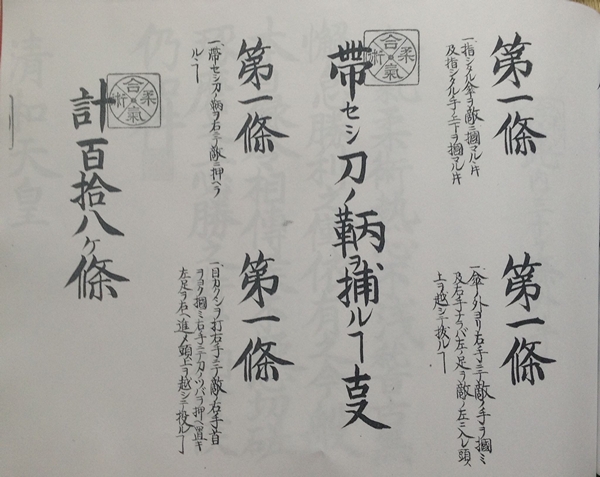

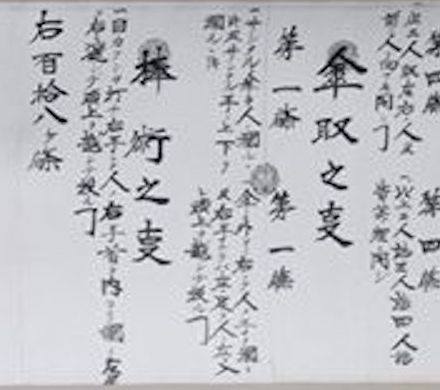

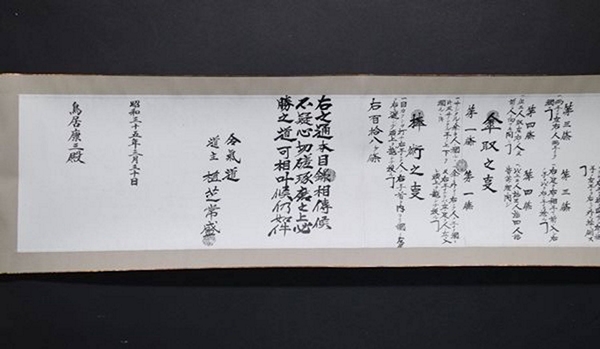

Hiden Mokuroku signature page

Here is the signature page of the 1925 scroll. signed by the student of Sokaku Takeda Masayoshi Minamoto (武田惣角源正義), Moritaka Ueshiba Seigan Minamoto (源晴眼).

Clearly a Daito-ryu scroll, and clearly issued under the authority of his teacher, Sokaku Takeda. The same is the case in this scroll, also issued under the authority of Sokaku Takeda:

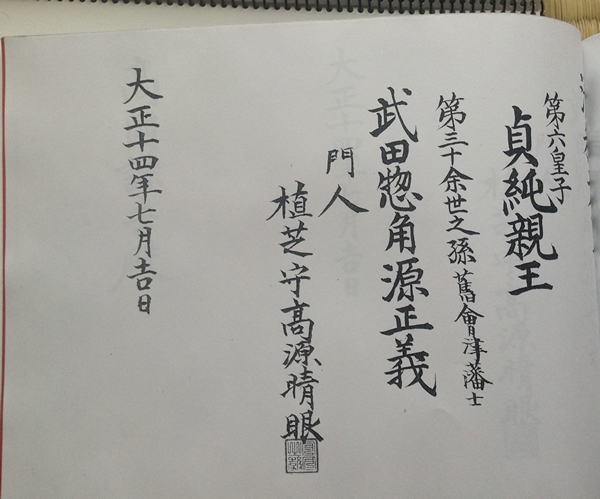

Hiden Mokuroku issued to Minoru Mochizuki in 1932

Hiden Mokuroku issued to Minoru Mochizuki in 1932

“Ueshiba Moritaka, student of Takeda Sokaku”

And here’s yet another scroll:

Aikido Hiden Mokuroku

Aikido Hiden Mokuroku

The picture quality is not quite as good, but there are some interesting things that we can pick out here.

- The scroll now reads “Aikido” rather than “Aiki-jujutsu”.

- The structure of the scroll is identical to the Daito-ryu scroll.

- The title of the scroll is “Hiden Mokuroku”, the same as the Daito-ryu scroll.

Aikido Hiden Mokuroku detail

Aikido Hiden Mokuroku detail

Here is a portion of the scroll in greater detail. Like the Daito-ryu scroll, this scroll contains a section on umbrella techniques. This one also contains a section on Bo (staff) techniques.

On the left hand side it specifies that this scroll contains 118 techniques, the same as the 1925 Daito-ryu scroll.

Aikido Hiden Mokuroku signature page

Here is the signature section of the scroll. Sokaku Takeda’s name no longer appears on the scroll, instead it is signed by Aikido Doshu Tsunemori Ueshiba (a name that Morihei Ueshiba often used after the war).

The date that the scroll was issued reads March Showa year 35 – 1960.

So…here is some of what we have:

- 1922 – Morihei Ueshiba is certified as an instructor in Daito-ryu, he has little experience in other martial arts at the time.

- 1922-1936 – Morihei Ueshiba is documented as teaching Daito-ryu under the authority of Sokaku Takeda.

- 1933 – Morihei writes Aikijujutsu Densho, a Daito-ryu instructional manual.

- 1936 – Takuma Hisa compares what he was doing to Sokaku Takeda and finds that they are both doing Daito-ryu. Sokaku Takeda takes over the Asahi Shimbun dojo and Morihei Ueshiba goes off on his own.

- 1940 – Takuma Hisa publishes Morihei Ueshiba’s Aikijujutsu Densho as a Daito-ryu manual.

- 1949 – Morihei continues to enroll students as students of Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu after the war.

- 1954 – Morihei Ueshiba publishes Aikido Maki-no-Ichi, which duplicates the technical explanations and technique illustrations of Aikijujutsu Densho. He teaches post-war students from this manual.

- 1957 – Lee Price is told that there are 2,664 techniques in Aikido by Morihei Ueshiba for the American TV show “Rendezvous with Adventure” (this may have been a translation error from the usual number of 2,884 techniques cited by the Takumakai) rather than the greatly reduced number of techniques in the post-war Aikikai. Morihei Ueshiba states that the art was founded by Minamoto Yoshimitsu in 1120, that it was handed down through the Takeda family, and and is represented its legitimate heir – not the founder. When asked when Aikido began, Morihei Ueshiba says “about 50 years ago”. Remember that this is 1957, so that would make 50 years ago about the time that he met Sokaku Takeda, well before the war.

- Morihei Ueshiba teaches the same techniques in Iwama after the war in the 1950’s and 1960’s as were documented in the 1938 technical manual Budo.

- Morihei Ueshiba issues Daito-ryu certificates, with the name changed to Aikido but with all of the other particulars preserved, as late as 1960 – and actually much later, in scrolls that are privately held.

I’m sure you see where I’m going here:

- Before the war Morihei Ueshiba was a Daito-ryu instructor under Sokaku Takeda, taught Daito-ryu for many years and issued licenses in Daito-ryu.

- What Morihei Ueshiba was teaching and distributing after the war in the 1950’s and 1960’s was essentially the same material that he was teaching and distributing before the war – Daito-ryu, right down to the certificates and the name in the enrollment book.

- There was no phase shift in core technology, or radical invention of new martial technology.

- That there was a basic continuity in the thread of his training and teaching as a student and teacher of Daito-ryu from 1922 through to his death in 1969.

Comparing the continuity of Morihei Ueshiba’s technical legacy visually

As Masatake Fujita, who spent most of every day with Morihei Ueshiba during the last two years of his life, put it:

Q: In terms of technique, did you notice a change in the Founder while you were watching him?

A: No, there wasn’t really any change. That’s probably true even from before the war, because even when you watch the video tape from Showa year 12 (1937), the year I was born, that’s true (*Translator’s note: this is actually the Asahi News demonstration from 1935). However, there were some techniques from that period that are gone today. I am teaching those kinds of techniques now, but of course it’s difficult.

“No, there really wasn’t any change.”

In other words, Morihei Ueshiba’s legacy was, in actuality, what some people might call “Ueshiba-ha Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu”, Morihei Ueshiba’s own branch off the tree of Sokaku Takeda’s art.

For more on the what happened to the diverging legacies of Morihei Ueshiba and his son Kisshomaru, check out Mark Murray’s essay “The Ueshiba Legacy” – Part 1 and Part 2. You might also be interested in Aikido Journal Editor Stanley Pranin’s essay “Is O-Sensei Really the Father of Modern Aikido?“.

Published by: Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI

Leave a Reply