From left to right: Lujian Xing, Moriteru Ueshiba, Kisshomaru Ueshiba,

Yucai Qiu (All China Sports Federation), Tetsutaka Sugawara

from “Aikido and Chinese Martial Arts: Its Fundamental Relations”

by Tetsutaka Sugawara and Lujian Xing

“At the master level, all boxing becomes one. All is moving with the tanden.”

“Internal Strength” magazine was published by Mike Sigman in 1993 and 1994. Only six issues were ever published, and it is no longer generally available, but some of the articles have been archived on the “Internal Strength” website.

A friend of Mike’s, Mike Jones, later started “Internal Martial Arts” magazine using the same formatting as the old “Internal Strength” magazine.

Mike (Sigman) sent me this article about Tetsutaka Sugawara (菅原鉄孝) by Jason Chung from issue 6 of “Internal Martial Arts” and suggested that I post it here so that it would remain available to the general public. It was relevant to discussions that were going on in April 2000, and I hope that it you will find that it is still relevant to discussions ongoing today.

While I was living in Japan I met Tetsutaka Sugawara through one of my instructors, Hiroyuki Hasegawa (長谷川弘幸), who trained with him in Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū (天真正伝香取神道流) , and I have always been impressed by the variety and depth of his research projects.

Here is a short biography from the Sugawara Budo website (also known as the Sugawara Martial Arts Institute / 菅原総合武道研究所):

Tetsutaka Sugawara was born in Hokkaido in 1941. In 1960, he began Aikido at the Hombu Dojo, Tokyo, under O-Sensei Morihei Ueshiba, founder of Aikido. In 1961, he became uchideshi under O-Sensei at the Ibaraki Dojo.

In 1964, he returned to Tokyo and entered Chuo University. In 1973, he established Minato Research and Publishing Co. (currently Sugawara Martial Arts Institute, Inc.) In 1975, he entered the Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu receiving the ‘kyoshi’ instructor’s license in 1986.

April 1992, introduced Aikido to Shanghai Institute of Physical Education, Beijing University of Medical Science. November 1992, received Kyoshi-license of Okinawan Goju-ryu Karatedo by Yasuichi Miyagi. June 1993, introduced Aikido to Wuhan Institute of Physical Education, Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medical Science in China. May 1995, received Aikido 7th Dan by Kisshomaru Ueshiba. Introduced Aikido to Chengdu Institute of Physical Education in China. Received the Lecturer’s License of Shanghai Institute of P.E. He is currently visiting 12 countries teaching Aikido and Katori Shinto Ryu.

Tetsutaka Sugawara: Aikido and Taiji

by Jayson Chung – © Six Harmonies Press, Michael W. Jones, Editor/Publisher

from Internal Martial Arts magazine, Issue 6 (April 2000)

It is a given in Aikido that the many spiraling movements of one’s arms and hands as one performs throws, take-downs and controls should be an integrated component of some seamless, whole body movement. We are told that power should emanate from the center through a relaxed body, a quality easier to discuss enthusiastically over a beer after practice, of course, than to exhibit on the mat.

My brief initial exposure to Taiji through a Zheng Manqing (Ch’eng Man-ching) style class had impressed me regarding how I could improve my Aikido posture and leg work by using Taiji methods. Later, when I first began to make progress in “solving” Chen style Taijiquan silk-reeling exercises, I realized that here was a key to the spiraling coordinations that I was trying to work out on the Aikido mat.

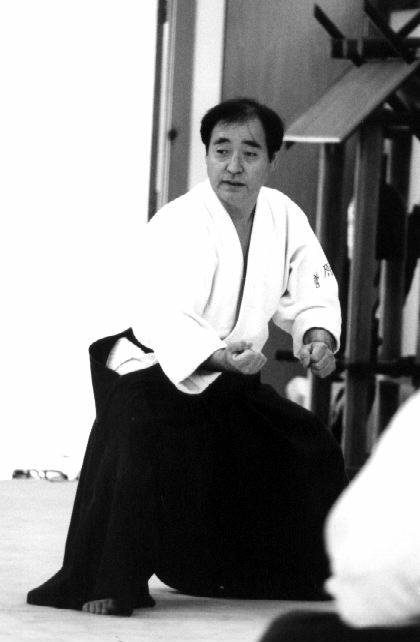

Tetsutaka Sugawara’s visit to Madison, Wisconsin gave me an opportunity to speak to another Aikidoist in depth with similar enthusiasm for Taijiquan — but, unlike me, deep experience and formidable skill, to boot — about the influence of Taijiquan on his Aikido. I should point out that this article is a one-way look at the relationship between Taiji practice and Aikido practice. That is, my conversation with Sugawara Sensei focused on his constructive criticism of various aspects of Aikido training that Taijiquan practice could possibly help to address.

At one point, I asked Sugawara Sensei what Aikido practices or ideas could help improve Taijiquan training. Sugawara’s straightforward answer was that since he was only learning Taijiquan and was not accomplished at it, he could not offer any opinions on that.

Crossover Interests

Tetsutaka Sugawara was first introduced to Taijiquan during a trip to China to research the background of Gojuryu Karatedo with a colleague who is an instructor in that art. Sugawara Sensei has traveled to China a number of times to establish cross-cultural relationships and conduct research into martial arts, especially sword arts.

In Fuzhou, Sugawara met Xing Yanling, who taught Chinese martial arts at Fujian Medical College. Xing Yanling had studied Taijiquan at Fujian Teachers College and Wuhan Institute of Physical Culture. Eager to learn Taiji, Sugawara invited Xing Yanling, who wanted to go to Japan to study the Japanese language, to teach Taiji at his Aikido dojo in Tokyo. For ten years now, she has taught Taiji in Tokyo and studied Aikido with Sugarawara.

Sugawara Sensei’s Taiji practice is based on simplified forms. He first learned the 24- and 48-movement simplified forms and then studied the Chen style 36-movement simplified form based on the Laojia Yilu. Tetsutaka Sugawara, Xing Yanling and Xing Lujian (no relation to Yanling), another Chinese martial artist who studies and teaches at Sugawara’s dojo, collaboratively explore the possibilities of combining ideas and techniques of Aikido, Taijiquan and other arts.

Evidence of this showed up as Sugawara taught an Aikido seminar in Madison. On a more visible level, his techniques were liberally sprinkled with joint locks and pins that were as likely to be drawn from Chinese qinna as from the orthodox vocabulary of Aikido controlling techniques. He said that the typical position of an Aikidoist in hanmi (Aikido’s basic triangle stance) was “not so perfect,” and he favored lowering the hips more in the “sunk” style of Taiji.

Also, he taught a modified form of the open posture and stance used in the foundational exercise tai no tenkan. In the traditional stance, the arms are extended with palms facing skyward. In Sugawara Sensei’s variation, the arms are somewhat less open and held with more curvature and the palms are turned inward. The arm posture bears a similarity to a “holding ball” arm position of Taiji standing practice. Sugawara favors this variation because he feels it strengthens the body posture and makes the arms more stable against forces from various angles.

Warm-up routines included separate exercises focusing on hip rotations and waist rotations. This emphasis on delineating hip and waist movements is not commonly seen in Aikido and reflects Sugawara’s Chen style Taiji interests. Some whole-body exercises he taught consisted of soft, spiraling movements that reminded me of Chen style silk reeling exercises. Sugawara was not familiar with the term English term “silk reeling” or my rendition of the Chinese equivalent. However, he explained to me that the point of the exercises was to use all of the body’s joints together. He showed how the exercise could be done in, outwardly, a similar manner by just using “hand work,” and then showed proper whole body usage employing all the joints to produce movements alternating between forward and back, up and down.

Tanden (Dantian) Usage

On a subtler level, as Sugawara Sensei performed some techniques, I noticed that his midsection appeared more mobile than customarily seeen among Aikido practitioners. In Aikido, upper body movements generally are driven by the twisting of hips and, to a lesser extent, waist and the folding or unfolding of the hip joints, which is matched by an overall closing or opening along the spine.

In some of Sugawara’s movements, however, a more pronounced use of the waist was evident. For example, in a kokyu nage throw directed to the rear, a subtle vertical rolling of the midsection led the sweeping movements of the arms.

In seated kokyu tanden ho (an exercise wherein one practitioner tries to connect with, then un-center his partner who grabs him by the wrists), Sugawara’s midsection rolled to the side and forward as he directed his power through his partner’s center and toppled the partner to one side.

Sugawara Sensei did not make much of these torso habits during the seminar classes, but when I asked about them privately, he showed how their purpose was to direct his power in particular directions. He said that Aikidoists need much more tanden (equivalent to Chinese dantian) training. Evidently, for Sugawara, Chinese internal exercises address this need quite well.

“Lots of times,” he said, “we use too much arm, not enough tanden.” The power should always come from the tanden and then be transferred through the body, through the arm, to the tip of the weapon, or the hand and fingers.

Circles and Spirals

When I asked him what Taiji principle he felt was the most important, he replied, “Spirals,” and when I asked what Taiji skills could help improve Aikidoists’ proficiency, he replied that Aikido students’ movements could be more circular. In many Aikido students’ technique, he explained, only the stepping is circular. (Interestingly, as I alluded in the Spotlight article in Internal Martial Arts, Issue 5, February, 2000), on the level of stepping, many of Sugawara’s movements seem assertively linear.)

Sugawara said that in Taiji, all parts of the body are circling. The wrist circles, the shoulder circles; ankles, knees and hips circle. The whole body, in addition to the stepping, is turning and spiraling. Although spiral movements are expressed in many, many Aikido techniques, the current Aikido student, he felt, did not have a good understanding of that principle. “We need to look at different styles,” he said, to improve our Aikido learning.

He also talked about spirals in terms of the tactical benefit of three-dimensional movements. Movement in all three dimensions is contained within the spiral. Sugawara said the Founder of Aikido taught the importance of that idea. Sugawara is careful to build that idea into his practice and teaching, both with regard to empty-hand and weapons training. He showed how spiral movements enabled one to be “very changeable,” how one could continuously adjust one’s attack using a spiral course, and how a partner’s attack along one dimension would suggest, through spiral movement, a counterattack along one of the other dimensions. During the seminar, he had students practice sequences that demonstrated spiral adjustments to one’s partner’s changes in direction.

Sugawara Sensei said his Taiji studies have helped him to better use twisting in his body and to keep the legs and knees flexible. He has developed new sword training routines, both for Katori and for Aikido, to emphasize these body skills and take advantage of spiraling, three-dimensional tactics. As he showed examples, the vertical dimension was sometimes given great emphasis by his extending a technique smoothly through standing and kneeling positions. “Sure, sure, because it (i.e., kneeling seiza) is Japanese custom,” he explained with a laugh.

Softness and Relaxation

To Sugawara Sensei, Taiji practice also can enhance Aikido competence in the area of developing proper softness and relaxation. In his eyes, softness and “warmth” in the quality of contact are more present, and clutching and grabbing less so, in Taiji practice than in Aikido practice.

Sugawara said the Founder tried to explain about harmonizing ki; and that was the goal of the Founder’s Aikido. “To feel partner’s feeling and spirit, then to change and flow . . . to catch partner’s spirit, this is the aiki situation,” he said. Modern martial arts are too stiff, Sugawara feels, and, unfortunately, Aikido is not an exception.

As an example, many Aikido teachers focus on the use of the hand as a blade (the familiar concept of tegatana, meaning hand-sword, reflects the derivation of basic Aikido techniques from sword movements), but Sugawara feels this is too limiting. “We should use all our surface in training, not only this edge,” he said. “If the hand is hard, the palm is tight, you cannot feel anything.”

Also, while taking ukemi (the role of uke, the partner who “receives” the technique being practiced), Aikidoists tend to use a very strong, hard grip to grab their partner. This kind of grip deadens one’s sensitivity and makes it difficult to detect partner’s changes and vary one’s movements accordingly. Sugawara advised Aikido students to study this point every day. “Current Aikido students, grabbing so strong. Everyone gripping, gripping, gripping. I want to change this situation. Too much grabbing. We must stop!” he said with enthusiasm.

One does need to know how to grab, however, especially when using weapons. Sugawara said the Katori technique, which he preferred, was to think of touching the thumb and middle finger together when one grabbed. Aikidoists are typically taught to grab hardest with the little and ring fingers. Sugawara believes the Katori approach gives a strong grip that is softer and warmer than the Aikido grip. It also lessens the likelihood that one will extend the index finger out in a vulnerable position, a bad habit which the Aikido grip tends to produce.

Sugawara Sensei taught a variation on the foundational exercise tai no tenkan that injected a more martial or self-defense flavor into the exercise while reflecting his concern about softness, warmth and sensitivity. The tenkan exercise involves executing a body turn to slightly redirect one’s partner’s attack and upset his equilibrium without interrupting his forward momentum.

In its basic form, the movement starts from a wrist grab and results in nage (the one “giving” the technique) standing almost in a mirror stance next to uke. The two are still connected by the wrist grab; however, the integrity of uke’s stance has been broken.

In Sugawara’s variation, nage turns slightly farther than 180 degrees, bringing his side against uke’s elbow, which already is in a weak, twisted-inward position as a result of the tenkan movement. This body contact against the vulnerable elbow provides an additional control point or can represent an attack against that joint.

During practice of this variation, nage’s body should make very full, soft contact against partner’s elbow. The body’s pressure against the elbow should be warm, as if it were a hand. Nage’s task was difficult to execute, but uke’s role was equally challenging.

Uke’s natural tendency was to tense his arm, and his body, against the pressure exerted by nage’s body. However, Sugawara stressed that it was uke’s objective, as well as nage’s, to make the contact full and soft. Any response from uke must be through an adjustment or movement of his whole body, not through any resistance of the arm. This small variation on tenkan, which emphasized the importance of softness and sensitivity for the sake of safety and practical skill, greatly increased the complexity of a familiar exercise.

Kokyu and Breath Power

While Sugawara Sensei is keenly interested in the varied benefits that different martial arts can bring to his practice, he is of the mind that all martial arts depend on the same core principles when practiced at a high level. For example, he said that, “At the master level, all boxing becomes one. All is moving with the tanden.” When I asked Sugawara about kokyu (which refers to the breathing or breath energy that animates movements or technique), he also said he felt the use of breathing is the same in Aikido, Taijiquan and Karate.

Sugawara pointed out that meditation style breathing and martial arts style breathing both differ from normal breathing but in contrasting ways. In normal breathing, inhalations and exhalations follow each other continuously. In meditation style breathing, an inhalation is followed by an exhalation and then a pause. In martial arts breathing, one inhales and then pauses slightly before releasing the breath in exhalation. However, he said it was not necessary to study breathing so explicitly. He felt that if one continued to study Aikido, or Katori, or Taiji or some other art, then one would naturally master the correct breathing for martial arts.

Sugawara Sensei used the word “keep” to describe martial breathing. At the top of the inhalation, there is a “little keeping” of the breath. This is a very important juncture in the execution of a movement. Then, on the exhalation, one does not just let the breath pour out but instead “keeps” or “saves” some breath while exhaling. The breath is not emptied altogether but measured out, to some degree, even during a rapid exhalation. Sugawara demonstrated with markedly aspirated strong abdominal exhalations. He also used the example of a big sneeze to help explain the rhythm of a powerful breath cycle. According to Sugawara, this is an important aspect of kokyu, although not understood well by many Aikidoists.

Sugawara said he believed Aikido’s breath power, or kokyu-roku, was the same as the breathing used to drive powerful movements in Taijiquan, and he regarded the particular use of the breath cycle to be at the heart of the internal approach to martial arts. The function of the inhalation is to store power (he said, “keep power to the tanden”). The out-breath releases that power.

Proper timing of the breath cycle is crucial. At first, the use of kokyu-roku may be too slow to be realistically functional, but with training it becomes instantaneous, and one matches the attack of one’s partner with kokyu. Sugawara noted, however, that in Aikido, where one typically trains with a partner, power normally is regulated, and some is kept in reserve. It would be very difficult and dangerous to use sudden, hard power in this kind of practice. Aikido practice techniques allow students to develop power while working with partners, and the release of the power is measured or gradual. The power can be soft or partially hard, but is not sudden and totally hard.

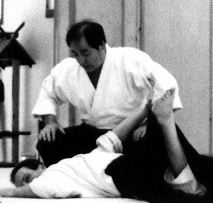

Accommodations can be made, however, as Sugawara showed during his seminar with a variation of a familiar kokyu-nage. The reference for this variation is a technique performed against an uke grabbing both of nage’s wrists that involves nage sliding behind uke and throwing him to the side and rear. In Sugawara’s variation, the circular sweep of nage’s arms was replaced by a sudden double-armed thrust as nage slid in behind uke’s center. (Photo above shows TS, without partner, loading up for such a thrust.) Because the thrust was aimed across, not at, uke’s body, the result was a throw (or should have been — we students had difficulty mustering the coordination needed to adequately power the release against partner’s grab) rather than a non-Aikido-like direct hit.

Sugawara said that students also could practice the sudden release of power in a modified Aikido context if uke, by prior agreement, escaped from the technique at the proper time. This would allow nage to complete the execution of the technique using full breathing power. This is a special circumstance, however, as it requires uke to withdraw from the actively engaged role of taking ukemi, which is central to Aikido practice. Weapons kata, of course, gives Aikido students a more orthodox opportunity to practice with kokyu. The principle is the same, with the goal being to transfer body power to the tip of the sword.

Always study

Sugawara Sensei mentioned the benefit of looking at other styles and points of views so often that this article must close on that note. He said that the Founder was a good model, having studied and borrowed from many other martial arts styles himself. O-Sensei also incorporated spiritual and religious influences into his art, of course, and some Aikido instructors put a lot of emphasis on those aspects. Some even tend to deify the Founder himself. Sugawara is not fond of this approach, because it tends to keep practitioners from critically evaluating what they know and what they have been taught. He feels Aikido needs more of a scientific approach.

Sugawara takes a cautious view concerning how much one really understands of what one has been shown and taught. Many claim to faithfully represent the essence of an art as passed down from their teachers. However, that assumes that one’s grasp of the knowledge that was conveyed was complete and accurate in the first place. Sugawara seems to prefer not to make that assumption. He is very aware that a martial artist’s understanding is shaped by the specific circumstances of his exposure to teachings, his ability to grasp what is being taught, and the teacher’s level of skill and point of view at the time he was taught. Therefore, rather than project some kind of orthodoxy, he prefers to continually examine his practice for flaws and seek ideas from elsewhere in order to test what he knows.

Sugawara Sensei noted that many instructors today are very busy teaching and, therefore, have little time to study. He cautions that it is necessary to continue to be a student, and to study every day.

Afterword:

A number of interesting videos of Sugawara Sensei are available from the Traditional Aikido of Santa Rosa website, including some videos of his Taichi style Aikido 42 Forms, in which he expresses Aikido principles in a Taichi-like format. I believe that I saw the first public demonstrations of these forms in Machida, Japan, in 2003.

Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI

Leave a Reply