“Takemusu Aiki” de Morihei Ueshiba, editado por Hideo Takahashi

This is the Spanish translation of the article “Aikido and the Unknown“, provided courtesy of Juantxo Ruiz .

Qué no sabemos y por qué no lo sabemos …

Cuando Sam Chin visitó Hawaii el año pasado, nos dijo (estoy parafraseando) que no es tan malo no saberlo, siempre y cuando usted sepa que no lo sabe. Eso me llamó la atención: ¿no es esta la primera parte del problema?

Cuando comencé en Aikido, había muy poca información disponible en inglés. Lo que estaba disponible era, lo sabemos ahora, altamente desinfectado (nota de Juantxo: vamos, que esa información no era completa y llegaba solo cierta parte): he aquí un buen ejemplo en el sitio web de Aikido Journal, y en el de Meik Skoss en su sitio web Koryu.com. Había muy pocos no japoneses que podían hablar japonés en ese momento, y mucho menos leer las fuentes originales, y la mayoría de los japoneses en el ojo público presentaban una representación más o menos uniforme de la historia y los detalles del Aikido.

Ahora, por supuesto, hay cientos de libros en inglés sobre el tema del Aikido, entonces, ¿cuál es el problema

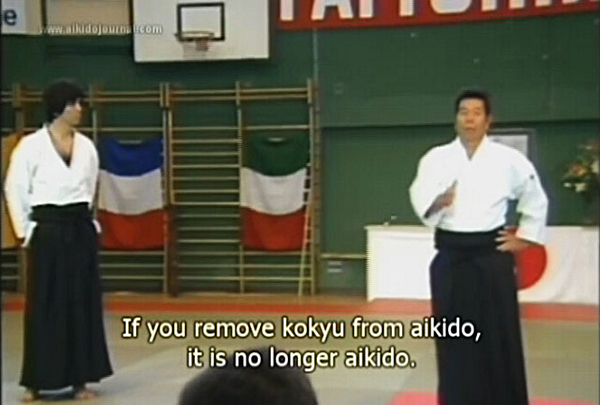

Pues bien, el material en inglés, especialmente el de fuentes originales, es más un resumen que un análisis detallado del material: todavía no se ha realizado una verdadera traducción académica.

De hecho, los materiales originales producidos por el fundador del Aikido, Morihei Ueshiba, son tan difíciles de leer que incluso la mayoría de los japoneses declinan leerlo en su propia lengua materna. Si lo leen, sin un fondo particular y experiencia, simplemente no hay decodificación. Peor aún, cuando lo leemos en inglés, no solo es a través de la lente del traductor y su comprensión, sino que está completamente fuera del contexto del mundo en el que vivió el Fundador, que es altamente especializado y complejo, y fuera de la contexto de ciertos otros campos especializados que son realmente esenciales para descubrir qué está pasando.

Dan Harden en el Taller Sangenkai 2015 en Hawaii

Dan Harden en el Taller Sangenkai 2015 en Hawaii

Lo sé, lo intenté, y no tuvo ningún sentido hasta años después a través de la lente de un mayor conocimiento en ciertas áreas, y por eso estaré eternamente agradecido a la generosidad de Dan Harden, que ha sido tan amable de compartir su entrenamiento con nosotros.

Eso no es para denigrar lo que se ha hecho hasta ahora en términos de traducciones al inglés, todo tiene que comenzar en alguna parte. John Stevens me dijo que consideraba que su traducción de “Takemusu Aiki”, que sigue siendo la colección más completa del fundador en sus propias palabras, es una especie de “Takemusu Aiki – Lite”, por lo que sería al menos semi -comprensible para una audiencia general.

Aún así, nos quedamos con una situación en la que la mayoría de los instructores y estudiantes de Aikido, ya sean hablantes nativos de japonés o no, no tienen idea de lo que el Fundador de su arte dijo o escribió de manera detallada.

Aha! Usted dice que su maestro es un alumno directo del Fundador, un uchi-deshi, y aprendió a los pies del maestro. Desafortunadamente, la mayoría de los uchi-deshi eran niños pequeños sin los antecedentes para comprender el contenido de las conferencias, o la paciencia para soportar el dolor de sentarse y escuchar al Fundador en las frías mañanas invernales, lo decían ellos mismos. Aquí hay algunos ejemplos: estos son de entrevistas en japonés que aún no se publicaron en inglés, pero Stan Pranin tiene varias citas similares en entrevistas en el sitio web de Aikido Journal:

P: ¿Por qué se ha perdido la sustancia (de la técnica de Aikido)?

A: Nadie escuchó lo que O-Sensei estaba diciendo. Simplemente intentaron recordar la forma externa de la técnica. Aunque O-Sensei dijo “¿De qué sirve copiar mi técnica? Si haces una técnica una vez, ya está terminada “. Debido a que hablaba como un Kami-sama (Dios), pensaron que nada de lo que él decía podía ser entendido, y ni siquiera intentaron prestar atención cuando escuchaban. Mucho más tarde, cuando olvidaron todo, a veces recordarían “Ah, eso es lo que eso significaba”. Es por eso que la práctica de la mayoría de las personas hoy está vacía. No miran otros tipos de Budo. Desde el principio, el valor de un Budo se determina mediante comparaciones con otros Budo.

P: He oído que las conferencias fueron bastante largas.

A: las odiaba (risas). Hablaba sobre los Kojikki y otras cosas, pero mis piernas se quedaban dormidas y no podía entender nada, solo me hacía llorar. Pensar en esto ahora realmente trae cosas de vuelta.

P: ¿Es cierto que no hubo discusión técnica?

R: En términos de cómo aplicar técnicas específicas, algunas personas dicen que O-Sensei dijo esto o aquello, pero en lo que a mí respecta, nunca escuché ninguna explicación.

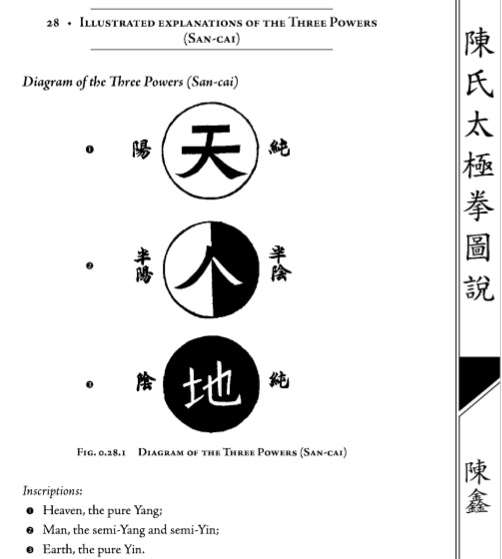

O-Sensei venía al dojo, mostraba algunas técnicas y luego se iba. Si tenia ganas, hablab un rato. Todos éramos jóvenes, por lo que en su mayoría solo queríamos seguir con la práctica. (sobre el contenido de las conferencias) Hablaba sobre los dioses: Izanagi, Izanami, etc. En Sakurazawa-shiki (Macrobiótica) tienen algunas ideas parecidas, así que pensé que estaba hablando de algo relacionado con In y Yo (yin y yang en japonés), pero eso es todo lo que yo entendía.

P: El Fundador solía hablar mucho sobre el Kojikki (“Un registro de asuntos antiguos”), ¿no?

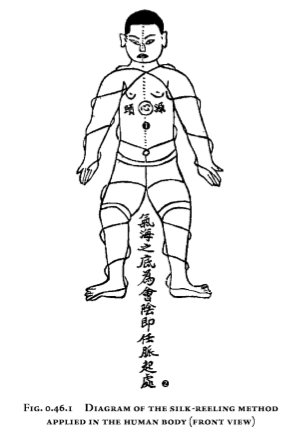

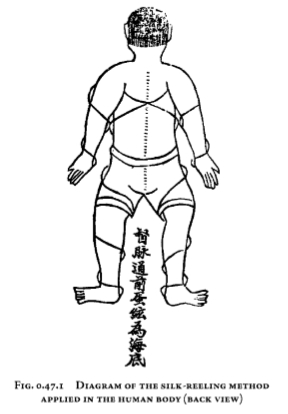

A: Sí. Una vez, el Fundador trajo un diagrama del cuerpo humano y dio una explicación mientras sostenía una copia del Kojikki en una mano. Mientras señalaba los músculos y los huesos en el diagrama, dio una explicación muy detallada, diciendo cosas como “Esto es Naohi (espíritu correcto)”, y así sucesivamente. Sin embargo, en ese momento solo me preguntaba qué significaba todo eso. Fue solo una vez, así que no puedo recordar los detalles muy bien.

P: ¿No hubo ninguna explicación de las técnicas?

A: No, no. Solo discursos difíciles sobre el Kojikki, y luego él te proyectaba y decía “¡Así!”. Sin embargo, a menudo dijo que el Aikido cambia todos los días.

Así que aquí está la primera parte del problema: la mayoría de las personas ni siquiera saben que no saben. Lo que eso significa es que la mayoría de la gente está haciendo alegremente lo que está haciendo sin tener idea de que hay, o debería haber, algo más; el entrenamiento en el que Morihei Ueshiba desarrollaba todos los días desde el día en que conoció a Sokaku Takeda en la posada Hisada en 1915 hasta que falleció en Tokio en 1969.

Ahora bien, ¿por qué no lo sabemos?

Creo que es posible defender firmemente que gran parte de los registros históricos fueron deliberadamente alterados u ocultados. El trabajo de Stan Pranin muestra mucho de eso.

También es posible prestar atención a un detalle que los estudiantes del Fundador omiten mucho: que lo que obtuvieron lo consiguieron al sentir, al ser proyectados directamente por el Fundador. Una corroboración de esto es que aquellos estudiantes que obtuvieron un poco o mucho de algo del Fundador tuvieron problemas para transmitir esas cosas a sus alumnos. Es fácil ver cómo esto lleva a un colapso en la transmisión, una degradación constante de habilidades donde los estudiantes del Fundador nunca igualan el nivel del Fundador, los estudiantes de los estudiantes nunca alcanzan el nivel de sus maestros y etc.

Peor que cualquiera de esas cosas es que muchos de nosotros nos hemos sentido cómodos sin saber realmente ni entender de lo que el Fundador estaba hablando. Pídale a la mayoría de los instructores de Aikido una explicación clara de los términos y objetivos expresados en “Takemusu Aiki” y obtendrá … muy poco. Es increíble, para mí, que un instructor en un arte se sienta cómodo al no entender claramente el discurso del Fundador de su arte.

Por último, por ahora, “¿por qué no nos importa?” – esta es otra cosa que me resulta increíble, pero supongo que es típica de las personas en general y no es un problema específico del Aikido. En general, las personas están contentas de hacer lo que hacen y lo que han estado haciendo, y cuanto más tiempo llevan haciéndolo, menos cuestionan.

Me sorprende cómo pocas personas, por ejemplo, cuestionan el sistema de clasificación “tradicional” en Aikido, aunque la “tradición” solo comenzó en la década de 1940 y realmente comenzó a ajustarse al intento del gobierno japonés de regular las artes marciales bajo el Dai-Nippon Butokukai.

Debería ser responsabilidad de todos y cada uno de nosotros en Aikido ser activos en el descubrimiento de lo que no sabemos, y cómo podemos aprender esas cosas, y preocuparnos por el proceso.

Además, creo que nos corresponde a cada uno de nosotros tener una comprensión clara de lo que el Fundador pensó sobre su arte, cuáles fueron sus objetivos técnicos, filosóficos y espirituales y poder expresar esas cosas de una manera clara y convincente.

De lo contrario, ¿cómo puedes decir que estás entrenando el arte de Morihei Ueshiba?

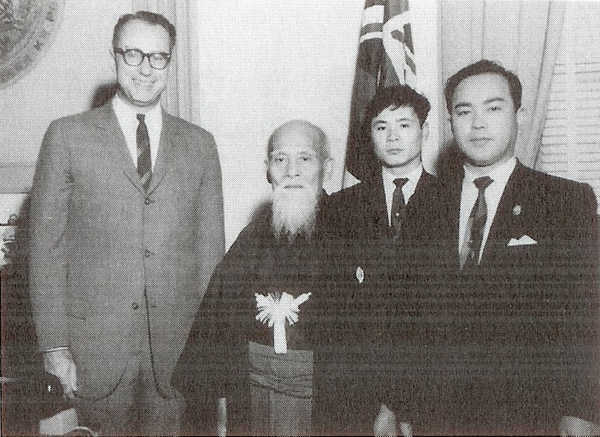

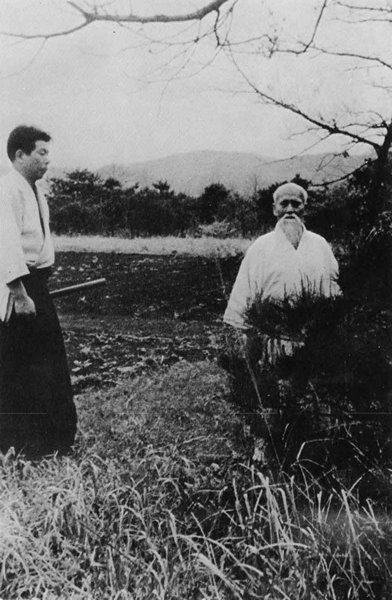

Morihei Ueshiba medita sobre Haleakala, Maui, 1961

Morihei Ueshiba medita sobre Haleakala, Maui, 1961

Published by: Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI

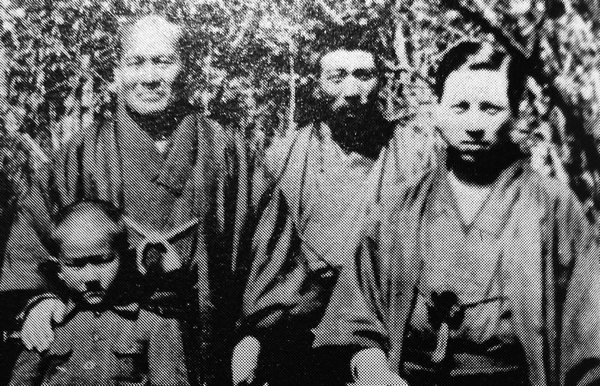

![Aikido, qué no sabemos y por qué no lo sabemos … [Spanish Version]](https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/wp-content/media/takemusu-aiki-hideo-takahashi.jpg)

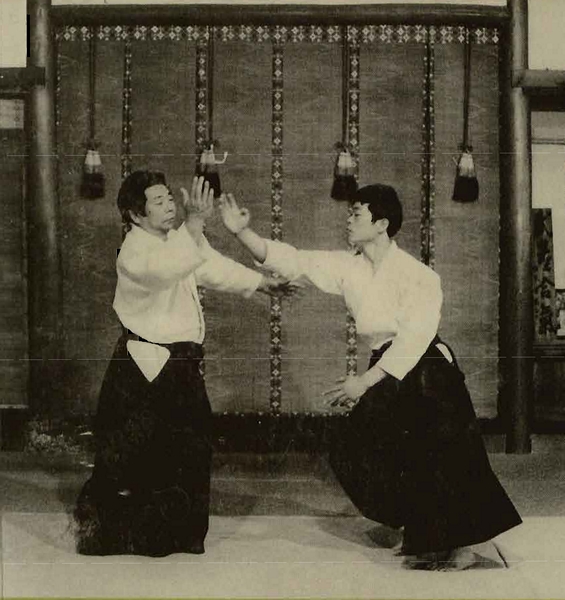

Aikikai Hombu Dojo Aikido Shimbun – January 1999

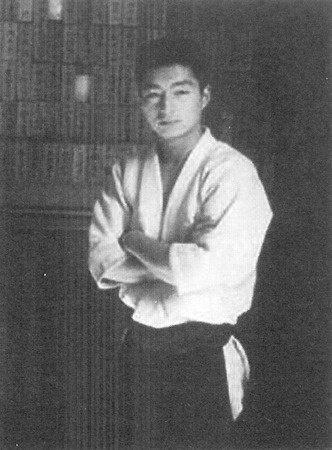

Aikikai Hombu Dojo Aikido Shimbun – January 1999 Kisshomaru Ueshiba in 1963

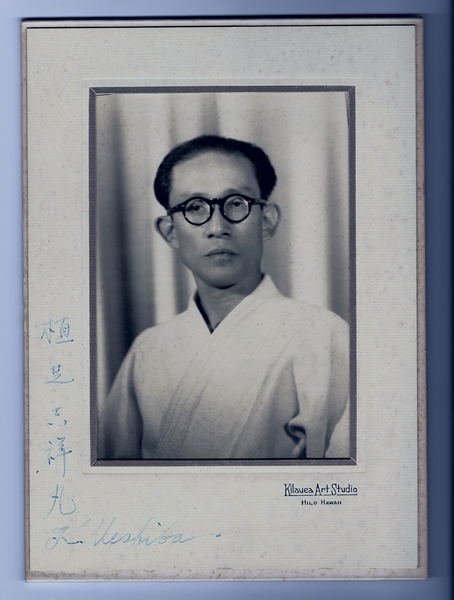

Kisshomaru Ueshiba in 1963 Kisshomaru Ueshiba in Hawaii

Kisshomaru Ueshiba in Hawaii Kisshomaru Ueshiba’s wedding in Iwama

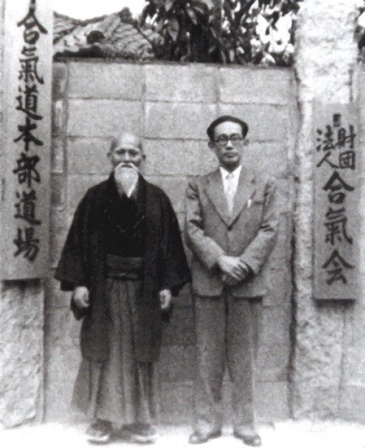

Kisshomaru Ueshiba’s wedding in Iwama Morihei Ueshiba and Kisshomaru Ueshiba

Morihei Ueshiba and Kisshomaru Ueshiba Kisshomaru Ueshiba at the old Aikikai Hombu Dojo

Kisshomaru Ueshiba at the old Aikikai Hombu Dojo![Aikido und die schwebende Himmelsbrücke [German Version]](https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/wp-content/media/utagawa-hiroshige-izanagi-izanami_2.jpg)

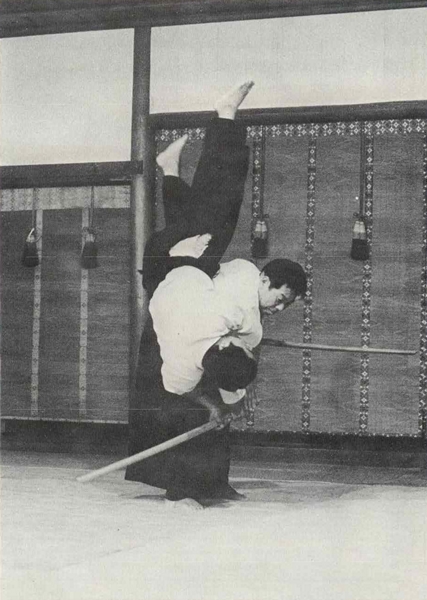

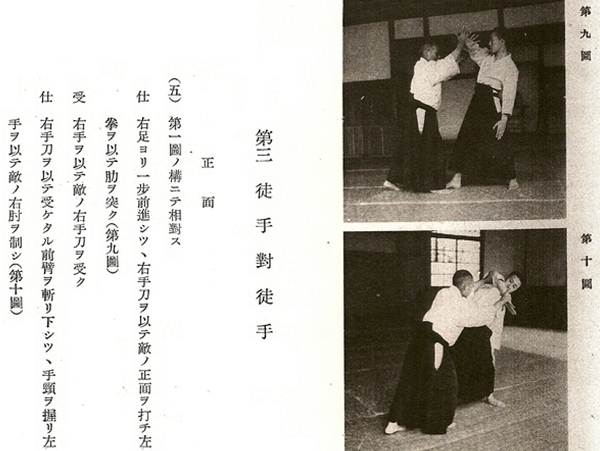

Morihiro Saito – “Traditional Aikido – volume 2”

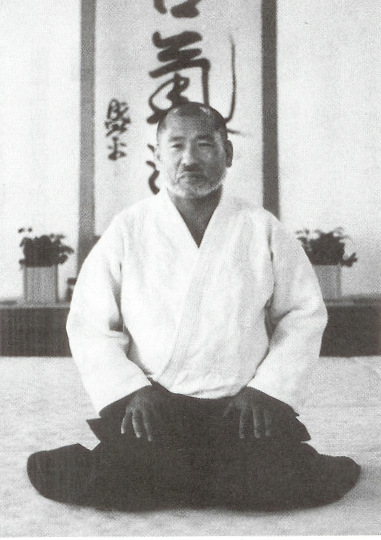

Morihiro Saito – “Traditional Aikido – volume 2” Ni-Dai Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba at Aikikai Hombu Dojo

Ni-Dai Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba at Aikikai Hombu Dojo Morihiro Saito teaching from the 1938 technical manual “

Morihiro Saito teaching from the 1938 technical manual “ Morihiro Saito – “Traditional Aikido – volume 3”

Morihiro Saito – “Traditional Aikido – volume 3” Aikido Journal Editor Stanley Pranin translating for Morihiro Saito

Aikido Journal Editor Stanley Pranin translating for Morihiro Saito Morihiro Saito and Morihei Ueshiba – 1954

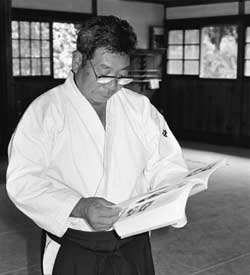

Morihiro Saito and Morihei Ueshiba – 1954 Morihiro Saito reading “

Morihiro Saito reading “

Morihiro Saito and Morihei Ueshiba

Morihiro Saito and Morihei Ueshiba Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba’s grave in Kozanji

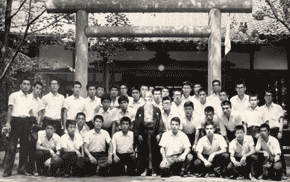

Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba’s grave in Kozanji  Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba with students from Meiji University in Iwama

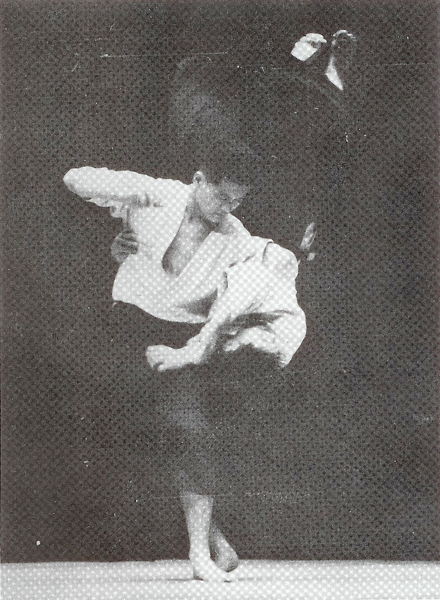

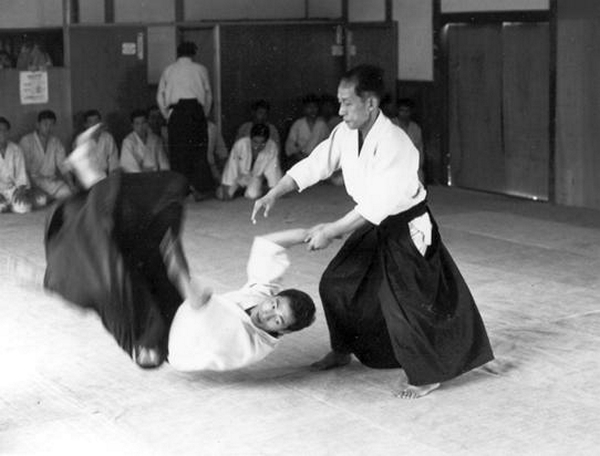

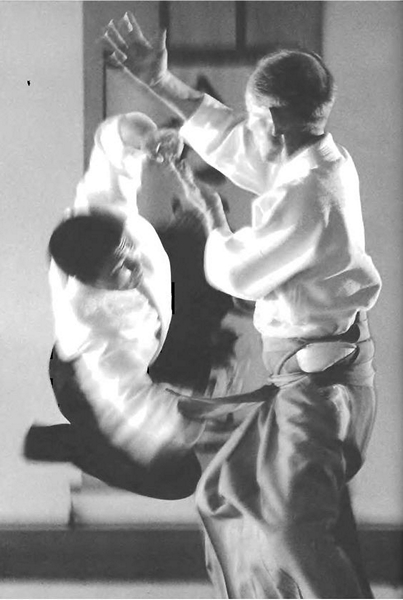

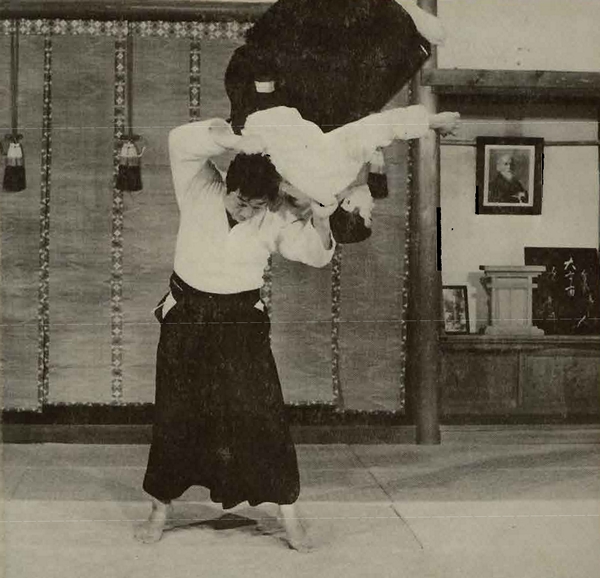

Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba with students from Meiji University in Iwama Morihei Ueshiba initiates with an attack

Morihei Ueshiba initiates with an attack Demonstration for the Jieitai (“Self Defense Forces)

Demonstration for the Jieitai (“Self Defense Forces)