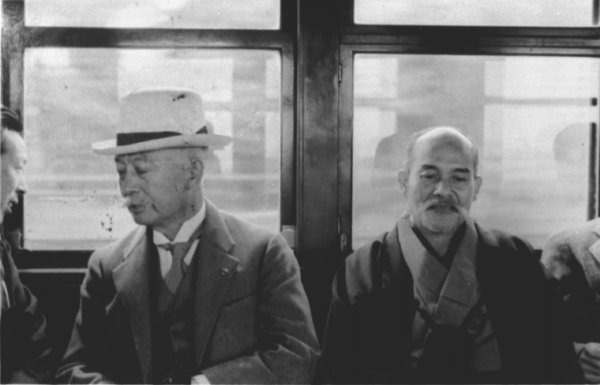

Morihei Ueshiba and Isamu Takeshita on the train

Morihei Ueshiba and Isamu Takeshita on the train

Isamu Takeshita (竹下勇) was an Admiral in the Imperial Japanese Imperial Navy and a diplomat who helped negotiate the end of the Japanese war with Russia.

A patron of the Japanese martial arts, he introduced President Teddy Roosevelt to his Judo instructor Yoshiaki Yamashita. A student and patron of Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba, he was instrumental in convincing Ueshiba to move to Tokyo and also introduced him to the inner circles of Japan’s military elite.

Admiral Takeshita also gave what was most likely the earliest demonstrations of Sokaku Takeda and Morihei Ueshiba’s art in North America.

Admiral Isamu Takeshita in Hollywood with child actress Jane Withers, 1935

Admiral Isamu Takeshita in Hollywood with child actress Jane Withers, 1935

During the summer of 1935, Admiral Takeshita made his fifth visit to North America. Stops included New Orleans, San Francisco, Washington DC, and Seattle. His purpose was to tell US audiences that the international press misinterpreted Japan’s role in China. The Japanese objective, he said, was not to spread the Japan’s Co-Prosperity Sphere but to stop international Communism. “No Japanese warship has ever crossed the Pacific except on a mission of peace,” he said during a radio broadcast in San Francisco. “No Japanese soldier has ever come to these shores except on a similar mission.”

While in the United States, Takeshita demonstrated aikibudo to judoka and reporters. “I spend at least two or three hours a day with my pupils,” he said. “Ju-jitsu or kendo is an art as far as a foreigner is concerned, but it is also in character-building… Character is the most important thing from beginning to end.”

According to Takeshita, there were 3,500 holds in his style. Rather than using force to overcome an opponent, the idea was to throw him almost without touching him. The way this was done was by using the opponent’s own energy against him. While Takeshita believed that aikibudo was a dangerous art for a young man, he thought it an excellent method for older men and women. He concluded by saying that it provided excellent training for politicians, as without it he would have become exhausted from all the handshaking Americans expected!

In Washington DC in September 1935, US newspapermen asked Takeshita about his “jiu-jitsu”. “Flexing the muscles of his arms and grinning,” said the New York World Sun Dispatch afterward:

The admiral offered to illustrate what he called a more effective manner of combat known in Japan as aikibudo.

One man, allowing curiosity to overcome caution, volunteered. Like a flash the admiral had the newspaper reporter on the floor, too surprised to do more than gasp.

‘I was very gentle with you,’ Admiral Takeshita said. ‘You see, I could very easily have killed you instantly.’

On his way back to Japan in October 1935, Takeshita also demonstrated aikibudo to Japanese American newspapermen in Seattle. His partner in the demonstration was Yasuyuki Kumagai, 5-dan, the head instructor of the Seattle judo club known as the Seattle Dojo. “The admiral smiled and told Kumagai to get set,” the Great Northern Daily News reported afterwards.

Both men took the judo pose, and with a sudden movement that was faster than most of the witnesses could catch, Takeshita thrust out an open hand, fingers rigid and pointing to Kumagai’s mid-section.

That was all, but Kumagai, who knows a little of vulnerable spots on the human body, was startled as well as convinced.

‘One inch more and I would have been unconscious or be writhing on the ground in pain,’ said the husky judoist. And most of the bystanders believed him.

Aikido Comes to America: September 1935

Journal of Combative Sport November 1999

By Joseph R. Svinth

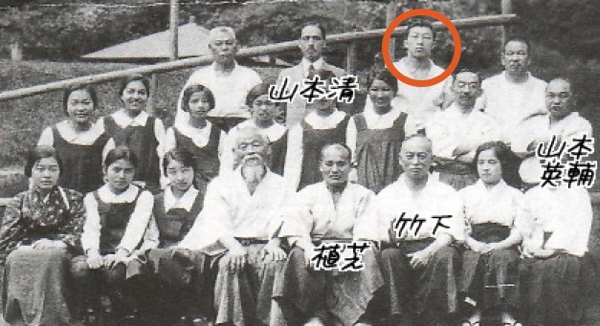

The young Kenji Tomiki with Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba

The young Kenji Tomiki with Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba

Kenji Tomiki (富木謙治) began training under Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba in Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu in 1926 after being encouraged to meet Morihei Ueshiba by Hidetaro Kubota (who later changed his name to Nishimura), a fellow Judo student at Waseda University.

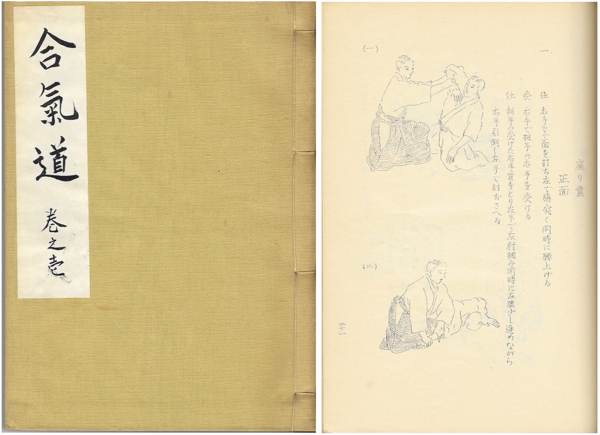

The first known book published by Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba (“Moritaka Ueshiba” at the time of publishing) was the 1933 training manual published in English under the name “Budo Training in Aikido“. This manual was initially given to his students as a kind of a teaching license (the full manual is available for free download from “Aikijujutsu Densho – AKA Budo Renshu, by Moritaka Ueshiba“). It is filled with illustrations depicting techniques taught at the Kobukan Dojo which were drawn by Takako Kunigoshi, a student at the Kobukan who began training shortly before her graduation from Japan Women’s Fine Arts University. The text portions of this work were largely compiled and edited by Kenji Tomiki.

In 1938 he became Morihei Ueshiba’s representative at Kenkoku University in Japanese occupied Manchuria (replacing Rinjiro Shirata, who had originally been chosen, but was conscripted into the military in 1937), and would become Aikido’s first 8th Dan in 1940.

You may also be interested in these two previous articles about Kenji Tomiki:

- Aikido Shihan Kenji Tomiki’s Goshinjutsu

- Kenji Tomiki: Judo Taiso – a method of training Aiki no Jutsu through Judo principles

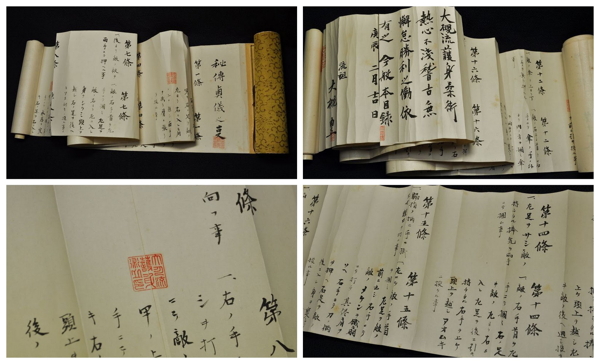

In the current article, created with original materials in Japanese provided through the assistance of Josh Gold and Aikido Journal, is a letter from Kenji Tomiki to Admiral Isamu Takeshita from 1928 (there is a simpler version of this article, without some of the annotations, is also available on Aikido Journal). At this point in time Tomiki had only trained for a short time with Morihei Ueshiba before entering military service, and the letter is written close to the end of that service. He details some of his thoughts and impressions of Morihei Ueshiba’s jujutsu, and the thoughts that it raised concerning Kodokan Judo.

This letter is actually mentioned by Isamu Takeshita in his diary:

September 21, 1928

Received a letter about the Aiki-Jujutsu of Mr. Tomiki, in Hirosaki [Aomori]. Comparing this with Kodokan-Judo interested me. [Note: Tomiki enlisted in the army in Hirosaki since the beginning of January, 1928]

– from “Summary of Isamu Takeshita’s Diary”

translation by Fumiaki Shishida

Enjoy!

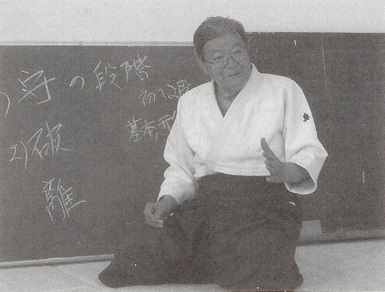

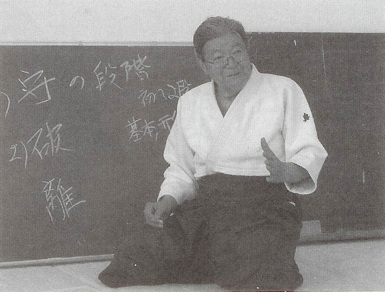

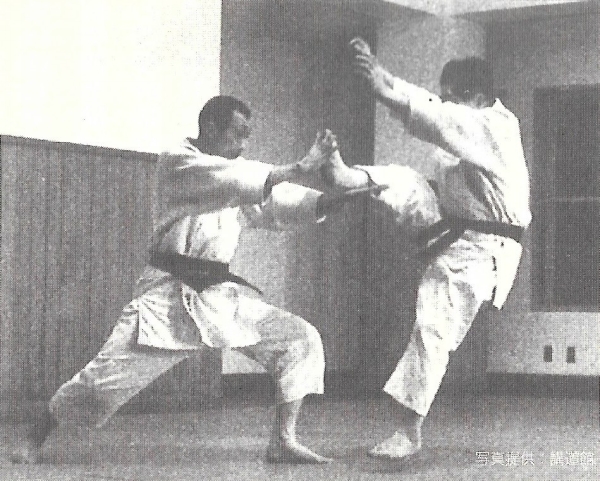

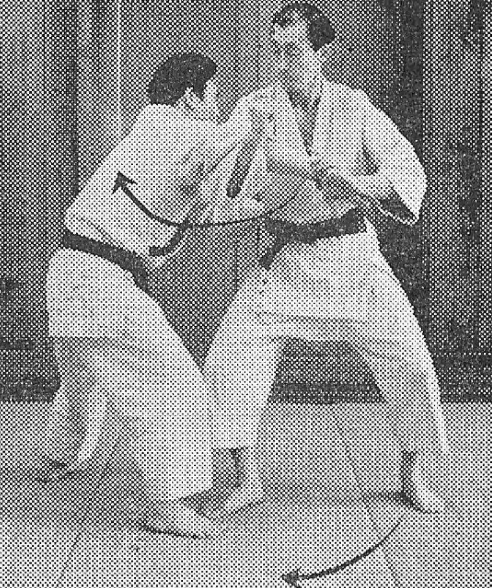

Kenji Tomiki defending against a front kick from Hideo Ohba in 1961

Kenji Tomiki defending against a front kick from Hideo Ohba in 1961

A letter from Kenji Tomiki to Isamu Takeshita

September 19th, Showa year 3 (1928)

To Mr. Isamu Takeshita, 3-5 Kuruma-cho, Shiba-ku, Tokyo-to

Sent by Kenji Tomiki, 31-5 Kachi, Hirosaki

Accounting Department Management Cadet

Heishin (“peaceful/ordinary news”, an honorific greeting)

Dear sir,

Since then I have not been able to send greetings for some time. I know that you and your wife have passed that time without difficulties, and I myself am still serving robustly in my employment by the army. The unusual heat wave that has been continuing in this area through the summer has gradually given way to autumn breezes and we can feel the chill in the mornings and evenings.

We will be dispatched to this year’s special war games that were moved up for the state ceremony to be held in the beginning of next month nearby Morioka, and fortunately we have been granted the honor of participating. I am attached to the headquarters for the 31st Regiment, 6th Battalion, and will be departing twenty-one days from tomorrow. We will start with combined arms training near Aomori and brigade and regiment level opposition, then directly after that proceed with provisional division opponents and finish with the Shinkyo large scale maneuvers (Note: possibly in preparation for the Japanese invasion of Manchuria).

Photograph commemorating the completion of the

Photograph commemorating the completion of the

Showa year 3 (1928) Morioka Special War Games

Only a month after the war games are completed I will be separating from life in the military. After my military discharge, It seems that I will be returning to Tokyo to become a burden upon everybody once more.

The other day I received a letter from Ueshiba Sensei. He has returned to Ayabe for a short time and will be returning to Tokyo in September. I was certainly happy to know that all of you are researching as usual, and that the number of enthusiastic practitioners grows with each passing day.

Looking back to last spring when I first received instruction from Ueshiba Sensei, and the short period until my enlistment a few months after that, those were truly days that held great significance to me.

In addition to an extraordinary revolution in my outlook on Judo, which I had researched for more than ten years since my elementary school days, the instruction and insight that I received into many of the questions and dissatisfactions with Judo that I had felt until that time clarified my thoughts on the current situation of Kodokan Judo.

Of course the number of days that I have been able to learn jujutsu from my instructor were limited, and even now I am still far from being able to plumb the depths of the deeper techniques. However, and this is based on the research of a short time, here are some of the things that I have been taught up until this time, or that have been wandering through my thoughts, with the knowledge that I have much more to be taught in the future.

Firstly, I have thought a great deal up to this point concerning what is called the Judo philosophy. I was unable to understand Judo’s place in the midst of the greater meaning of budo, but now I have come to believe that this is clearly so, that is, it is not that I was completely denying Kano Sensei’s philosophy of Judo, but that there are some questions concerning the presuppositions.

Is the single path of Judo included in the greater meaning of budo? If that is so, then then there is no particular need for argumentation for the viewpoint of Judo. Perhaps it is not that traditional Kendo, Judo and other bujutsu formed as individual entities with individual viewpoints.

This is what I was taught. What is called budo is a single integrated path, and this path is now expressed in an unbroken form as Kenjutsu, Sojutsu…the Bugei Juhappan (Note: the 18 traditional types of martial arts used by samurai in Tokugawa Japan, based upon earlier Chinese traditions). In past times all bujutsu was, in the end, the manifestation of a unique path of war. Therefore, both Kenjutsu and Jujutsu return in the end to a single path, and it is not necessary to divide Kendo from Judo in order to explain them. Actions of advance and retreat, body posture, breathing – they all must match with each other. However, the Judo and Kendo of the present day are virtually all in the process of becoming increasingly different from each other. Judo is not the same as something in which one holds a weapon, but both of those arts must adhere to the same basic principles. I gave myself up to the clarity of this truth through Sensei’s jujutsu.

In the ideal budo, as one progresses along the path their technical side progresses in parallel. This varies from what occurs in sports. In comparison to sports, in which records are maintained for the few years of one’s youth in the sport, in budo there comes a gradual increase in skill that accompanies mental conditioning continuing to old age. If we are looking towards this as an ideal, then there are a plethora of questions that arise concerning current Kodokan Judo. If we instead consider the case of Kendo, there are many practitioners who have the spirit to keep striving vibrantly past their 60’s, a better match with the ideals of budo.

These weaknesses have all been resolved by Sensei’s jujutsu.

It can be thought that Kodokan-ryu only hopes for growth within an extremely limited area. Therefore, with the drawbacks caused by the introduction of things such as modern boxing and Tode-jutsu (Karate) it can be felt that it has reached a practical dead-end in modern times.

If that is so, then from where do those weaknesses emerge? In the end, I think that it returns to the fact that the current Kodokan-ryu has grown based upon games for physical education rather then self-defense techniques. In that lies a great deal of the fault.

This can be understood through research into the origins of jujutsu and the sources behind the establishment of Kano Sensei’s Kodokan Judo. In the past the general jujutsu which has divided into many different schools was all for the purpose of shinken-shobu (Note: 真剣勝負 – a match with a live blade. In other words, a fight that determines life and death). Then, from those ryu-ha various schools that focused on throwing techniques such as Kito-ryu (起倒流) and Yoshin-ryu (楊心流), or those which specialized in striking (atemi) and holds such as Tenjin Shinyo-ryu (天神真楊流) and Yoshin-ryu (楊心流) differentiated themselves. However, the long and short of it is that defense against attacks was the primary focus, so that joint techniques were the most common. Consequently, Kano Sensei removed the joint techniques from those schools, avoided striking (atemi), chose the least dangerous strategies and established a Kodokan Judo that was appropriate for modern times. Then a variety of competitive methods were established from the most interesting principles and finally we have what is thriving today. On the other hand, it ended up as being completely a sport. Ueshiba Sensei would often say “Are things like Kodokan Judo useful? That’s not real bujutsu.”, and actually the reality is just that. Looked at from the viewpoint of self defense it’s completely powerless. And then, looked at from the viewpoint of true bujutsu it’s at the point of heresy. However, if one looks at it from the point of view of a sport then I think that it functions very well. I believe that here are the current reasons for modern Judo.

So in the end the problem must become “Which reason for Judo’s existance is most common in modern times, as self-defense or as a sport?”. Putting this problem aside for the moment, I would like to talk just a little about clarifying another side of the problem, the start and end of the controversy that engendered the Kodokan method of competition.

Kosen Judo – at the heart of the controversy over groundwork in Judo

Kosen Judo – at the heart of the controversy over groundwork in Judo

Sankaku-jime applied at the 1920 Kosen Taikai

In former years there were rival Judo matches between Senior Dai-ichi High School and Senior Dai-ni High School. As a result, although Dai-ichi High School had a leading third dan and a number of black belts, Dai-ni High School, who never had more than one or two black belts, would place higher in the competitions. What it came back to is that Dai-ni High School trained thoroughly in ground techniques, so Dai-ichi High School had no space in which to attack them. Kano Sensei was extremely critical of this:

“The foundation of Judo is shinken shobu. In times past ground techniques were used after the first opponent was fully overwhelmed in order to completely control a second opponent. In comparison to those times Dai-ni High School responds to an attack with ground techniques from the very beginning. This is not a proper thing to do for shinken shobu, extremely cowardly..”

A great controversy grew surrounding this.

We didn’t like ground techniques and we felt that the behavior of Dai-ni High School was underhanded. However, in terms of theory we knew that they were absolutely correct. That is, modern Kodokan Judo is sports. Therefore, as long as something does not violate the rules of the decided upon method of competition the goal is to win. Things such as shinken shobu were outside of the equation in this case. Accordingly, I believe that the use of Dai-ichi High School’s weakness in ground techniques to get the win is only reasonable. This problem of ground techniques versus standing techniques is a continuing problem, even today.

However, just delaying to a draw by responding unconsciously with ground techniques lacks an aggressive mindset – there is a great deal there that contradicts the warrior’s “battle to the death without surrender” attitude. And further, the fact is that one can practice throwing techniques for three or four years without developing real skill. In comparison, combining ground techniques with physical strength one can achieve significant results in only six months or a year, so they are very effective when going into competitive matches. What is prized in paired sports is victory in competitive matches rather than shinken shobu, so if the same mental and physical conditioning, sacrifice and effort is necessary to achieve that then I believe that it is best for us to take the route towards ground techniques rather than throwing techniques.

In the midst of those valued words from Kano Sensei that I mentioned before, modern Judo is gradually developing as a sport. Furthermore, I know that there is a dilemma in its gradual separation from shinken shobu (life or death attitude/intent.)

Translator’s Note: Jigoro Kano himself apparently had misgivings about Judo as a sport, expressed here to Gunji Koizumi in 1936:

I have been asked by people of various sections as to the wisdom and possibility of Judo being introduced with other games and sports at the Olympic Games. My view on the matter, at present, is rather passive. If it be the desire of other member countries I have no objection. But I do not feel inclined to take any initiative. For one thing, Judo, in reality, is not a mere sport or game. I regard it as a principle of life, art and science. In fact it is a means for personal cultural attainment. Only one of the forms of Judo training, so-called Randori or free practice, can be classed as a form of sport. Certainly, to some extent, the same may be said of boxing and fencing, but today they are practised and conducted as sports. Then, the Olympic Games are so strongly flavoured with Nationalism that it is possible to be influenced by it and to develop ‘Contest Judo,’ a retrograde form as Ju Jutsu was before Kodokwan Judo was founded.

Fulfilling His Duty as a Member: Jigoro Kano and the Japanese Bid for the 1940 Olympics

By Joseph R. Svinth

The benefits that come from Kodokan Judo are usually explained by the following four points:

- Methods of physical education. (“taiiku-ho” / 体育法)

- Methods of cultivating the spirit. (“shushin-ho” / 修心法)

- Methods of consoling the spirit. (“ishin-ho” / 慰心法)

- Methods of self defense. (“goshin-ho” / 護身法)

Shusaku Kiryu, University of Tsukuba Judo Team

Shusaku Kiryu, University of Tsukuba Judo Team

The purpose of this study is to clarify the background and intent of Kano Jigoro when he introduced the concept of ishinho (method to console the spirit) as one of the objectives of judo. Kano initially described the purposes of judo as taiiku (physical education), shobu (martial arts), and shushin (to master one’s spirit). Later, Kano add ishinho as an additional objective, but the reason he did so is unknown. Upon examining Kano’s writings and the aspects of judo popularized during this period, I was able to clarify the following:

- After 1883, judo penetrated schools as an extracurricular activity. Later, many judo clubs were established and they began holding inter-school matches.

- Kano showed that people who trained in the discipline of judo reaped the benefits of judo- taiiku, shobu, and shushin.

- In 1911 , judo became a standard subject in Japanese high schools. Later, Kano announced the inclusion of ishinho as an objective of judo, and added additional, factors (including the pleasure of exercise; the enjoyment of watching randori, competitions, and kata; and kata as an art form) to judo.

- Kano generated a new concept of ishinho against the background of his knowledge of dissatisfaction with normal gymnastics, the various benefits of judo, and the merit of athletic sports. With increasing inter-school matches, ishinho disappeared from Kano’s works, and students became involved in many scandals. Instead of ihsinho, Kano appealed to all people to improve this situation, whether they practiced judo or not.

The Introduction of the Concept of “Ishinho” to Judo

and the Thoughts of Kano Jigoro

– Shusaku Kiryu, University of Tsukuba

When I attempt to compare Ueshiba Sensei’s jujutsu to these points the following thoughts arise:

- There is certainly a danger of harm when elementary and junior high school students train normally for competition. If the instructor exercises appropriate caution then it can be suitable even for those who might be considered unsuitable for Kodokan-ryu such as the elderly and women. Therefore, I believe that on that point, or as concerns Judo as exercise, that it is by no means inferior.

- As a budo with a goal towards cultivating the spirit its goals are the some, so in the end it returns to a problem of the instructor, but I believe it to be far superior in terms of its great emphasis on spirituality.

- As for “Methods of Consoling the Spirit”, it is said that Kodokan-ryu appeals to feelings for the fine arts, but conversely, these things can also be seen in this jujutsu. As an example of a refined and elegant kata in Kodokan-ryu there is “Itsutsu no Kata” (五つの型), which expresses the feelings of the rushing of the waves, but in this jujutsu this is expressed, not in kata, but in the course of normal practice. Further, it is the same for “Ju no Kata” (柔の型), there are many points in this jujutsu that are extremely similar. However, in “Ju no Kata” the Kokyu is completely missing, making it end up spineless. It is the same for the movement postures – it is thought that when those are mastered by the women in Kodokan-ryu that they are able to able to attain a beautiful posture. However, the kamae of the legs and hips in this jujutsu and the movement of the body matches precisely to Noh dance, so I think that on this point it is actually ideal.

- Needless to say, as method of self-defense there is a remarkable difference. Firstly, as a conditioning method (鍛練法), and I was taught an enormous amount about this point. As a conditioning method there are two different methods. That is, one method favors randori over kata, and one method favors kata over randori. In addition to Kodokan Judo, modern Kendo also makes use of the former method, and this point can be thought to reveal a weakness of current-day bujutsu. In the end, this can be thought to be a consequence of the development of bujutsu that focuses on competition.

The harm of a focus on randori is that one tends towards the few techniques that one is skilled at and strays from the path, degenerating into simple physical strength. Although that is fine in terms of physical education, in order to grasp the true spirit of bujutsu I believe that clearly maturing the meaning of that bujutsu through kata before entering into randori is the way to eliminate mistakes. In this jujutsu the focus is on kata, but what seems to be a rather roundabout way to understand the meaning of that bujutsu is conversely a shortcut, and can be thought to eliminate mistakes. However, what I think is even more superior here is that although it is called kata it is not the same as the fixed fifteen throwing kata or the joint locking kata limited to so many techniques of Kodokan-ryu. They are flexible and freely adaptable to whatever situation arises – they are kata that are themselves randori.

When actually observing Kodokan-ryu and others and researching into their historical origins I was able to clearly ascertain the points of superiority of this jujutsu. Thus, the desire to understand the value of this jujutsu from the wider perspective of Nihon Bujutsu has been continuously on my mind.

As I said before, I have trained in Judo for many years, but in the end I never took it a single step past the point of view as a sport, and accordingly I researched it as a superior method of physical exercise, but when I emerged from my academic studies limits on my time, stamina, and location made me think that Judo was something that I would have to distance myself from. However, through an unexpected chance I was able to observe Sensei’s technique, and found a place for the Judo that I had thought to abandon and came to believe that here was something that I could continue to practice and improve forever as another form of exercise and a training interest. I enlisted just as I graduated last spring and leaving my classroom and my home behind then had the time to devote myself to Sensei’s instruction.

I would like to return to Tokyo after my military discharge and find some employment there, but I am also hoping to be able to spend a long time on research into everybody’s instruction in jujutsu, if it pleases you.

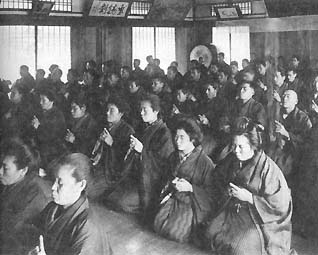

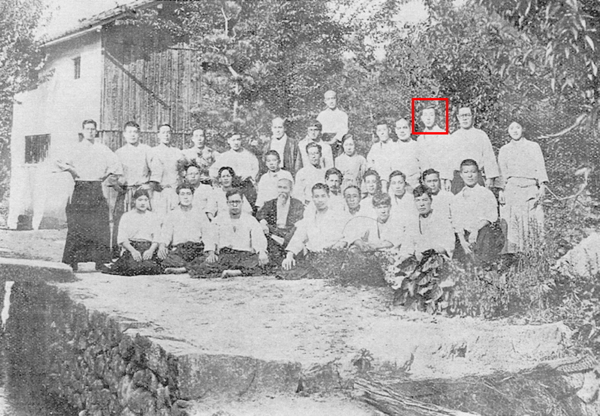

Chinkon Kishin Training at the Omoto compound in Ayabe, 1921

Chinkon Kishin Training at the Omoto compound in Ayabe, 1921

Finally, there is the issue of Sensei’s faith, I felt some uncertainty just as I visited Sensei in Ayabe last summer. My uncle and Mr. Kubota are examples, but there was not much support for my trip to Ayabe. However, I believe that Omoto-kyo and bujutsu are completely separate. While I was staying in Ayabe I always heard talk of faith from Sensei and other people, and perhaps due to my sceptical nature and the many subjects that I could not fully comprehend I was unable to understand this Omoto-kyo that is filled with miracles that surpass modern science. However, I have great admiration for Sensei’s faith and Sensei’s humble attitude towards the Gods. and I have thus deeply considered many points concerning Sensei’s techniques and his faith. It is not necessarily limited to Omoto-kyo, but it may be that it is with faith that bujutsu first reaches that level, that I may be been taught at a visceral level that bujutsu shugyo is something that in the end returns to faith.

Day by day the weather is becoming colder, I am praying for all of your health. Finally, thank you for taking the time to consider my ramblings.

September 19th

Respectfully,

Kenji Tomiki to the honorable Mr. Isamu Takeshita

Postscript: Please give my best regards to Mr. Shimoji and Mr. Yamamoto.

- This letter was transcribed by Professor of Intellectual History of the Japanese Martial Arts at Waseda University and Aikido Shihan of the Japan Aikido Association Fumiaki Shishida, from a copy received from Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Hombu-cho Katsuyuki Kondo. Kenji Tomiki’s handwriting was deciphered with the assistance of Mr. Seiichi Saito, who studied under Kenji Tomiki during his time at Kenkoku University in Manchuria, but there were a few places that were unclear and I hope for clarification at a later date. There may have been mistakes and imperfections in the copy, but it goes without saying that the wording of the text is the responsibility of the editor. With deep gratitude towards Kondo Sensei and Saito Sensei, Shishida Fumiaki – January 18th 1991.

- The original materials in Japanese were provided with the assistance of Josh Gold and Aikido Journal.

Published by: Christopher Li – Honolulu, Hawaii

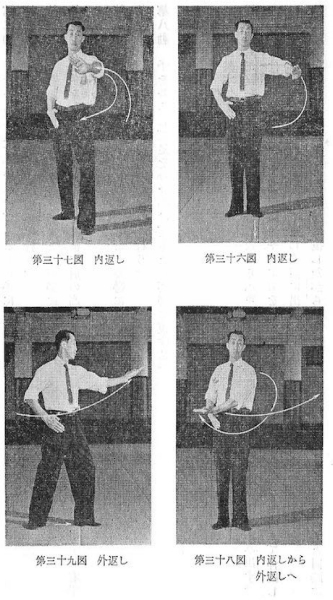

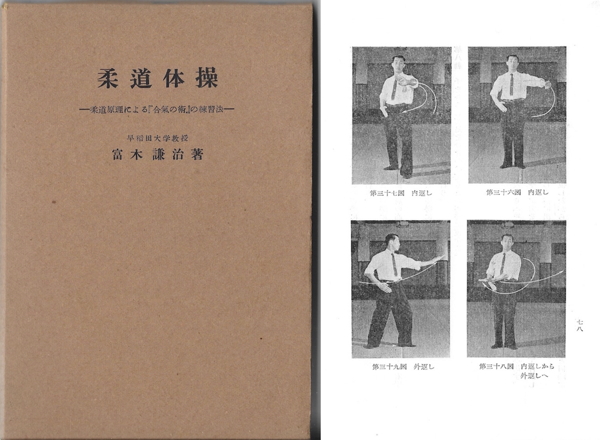

Daido Gakuin (大同学院) in Manchuria prior to 1945

Daido Gakuin (大同学院) in Manchuria prior to 1945 A page from “Judo Taiso” by Kenji Tomiki, 1954

A page from “Judo Taiso” by Kenji Tomiki, 1954 Kenji Tomiki shows a technique from the Goshinjutsu no Kata

Kenji Tomiki shows a technique from the Goshinjutsu no Kata “Introduction to Goshinjutsu” by Kenji Tomiki, 1974

“Introduction to Goshinjutsu” by Kenji Tomiki, 1974

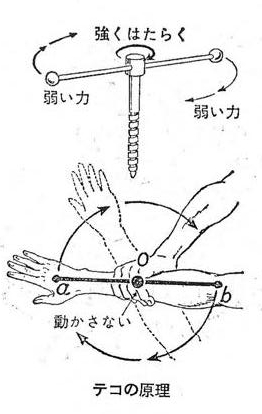

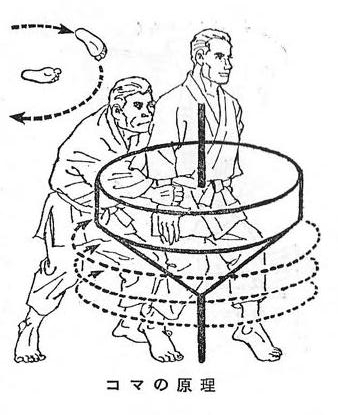

The principle of the spinning top

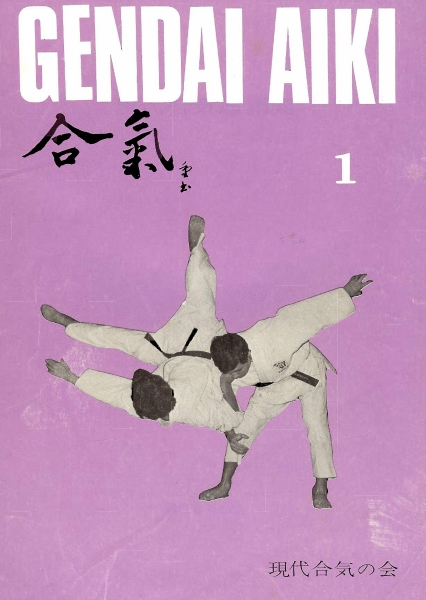

The principle of the spinning top The “Gendai Aiki” correspondence course

The “Gendai Aiki” correspondence course

Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba, back row center

Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba, back row center “Hiden Ogi” scroll issued in “Otsuki-ryu Aiki-jujutsu” by Yutaka Otsuki (大槻豊), 1940

“Hiden Ogi” scroll issued in “Otsuki-ryu Aiki-jujutsu” by Yutaka Otsuki (大槻豊), 1940 Kenji Tomiki and Morihei Ueshiba in Manchuria, 1942

Kenji Tomiki and Morihei Ueshiba in Manchuria, 1942