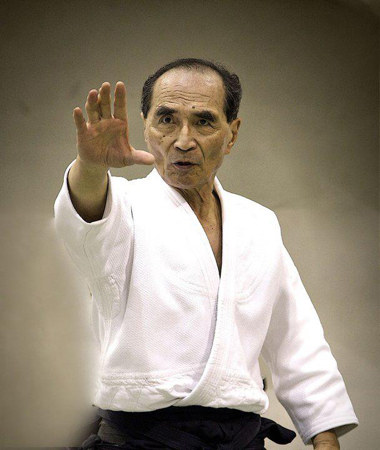

Hiroshi Tada Sensei in 2014

Hiroshi Tada Sensei in 2014

Aikikai 9th Dan Hiroshi Tada (多田宏) is one of the most influential instructors to come out of the post-war Tokyo Hombu dojo. Born in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan December 13th 1929, he began training at Aikikai Hombu Dojo on March 4th 1950.

Tada Sensei has appeared on the Aikido Sangenkai blog, both in “Aikido Shihan Hiroshi Tada: The Day I Entered Ueshiba Dojo“, and in the series of articles below:

“Aikido Shihan Hiroshi Tada: The Budo Body”

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8

“Aikido Shihan Hiroshi Tada – the Yachimata Lecture”

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5

This is the English translation of a short piece written by Tada Sensei that recounts some of his memories of Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba, it appeared in the Aikikai newspaper “Aikido Shimbun” in March 1998 (Heisei 10).

In October 1964 Tada Sensei was sent to Rome, Italy in order to help establish Aikido in Italy. He had been preceeded there by Professor Salvatore Mergè, who was mentioned by Tada Sensei in the article “Aikido Shihan Hiroshi Tada: The Budo Body, Part 6“.

The grave of Salvatore Mergè

The grave of Salvatore Mergè

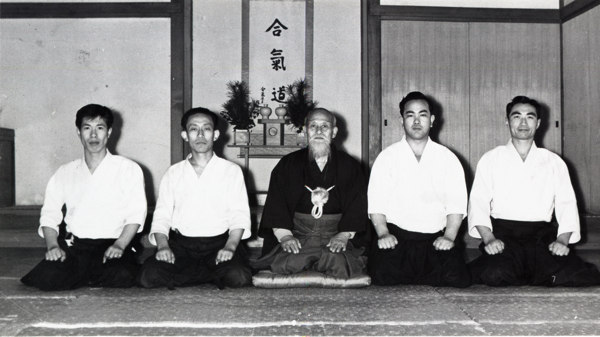

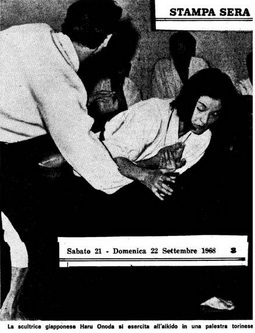

In 1942 Salvatore Mergè, a Japanese linguist and a member of the Italian diplomatic mission, became a student of Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba – perhaps the first occidental to do so. After returning to Italy in 1946 he taught privately and then helped to establish the first Aikido classes in Italy, taught by the sculptor Haru Onoda in 1959.

Haru Onoda in 1968

Haru Onoda in 1968

Here is some of the story of how he met O-Sensei, re-told by Stephen Serpieri, one of his Japanese language students:

“He had heard much of the Master’s deeds and of this new martial art he created, Aikido, but had never had the opportunity to see any of its “embukai” (public demonstrations). Intrigued by the stories that were made of this master and the reputation that had been created around him, he decided to go to his dojo and ask to be admitted as a student of Aikido. The house of Master Ueshiba and the attached dojo were far outside of Tokyo, and to get to the Italian embassy where Professor Mergè worked took over an hour by train. One day, before going to work, he went to the home of the teacher, saying that he was a lover of Japanese tradition and would like to know O-Sensei. He was made to wait in the atrium of the house for a time, but was eventually told to come back because the teacher was busy. He tried again at other times but the answer was always the same. Finally, after several failed attempts, he was brought into the house to get an answer to his request for a meeting with Master Ueshiba. He was made to sit in a room with an elderly gentleman who was reading a book and did not raise his head when he entered. After a short time the person reading stood up and, without a word, he left the room. … When the day came that he was able to speak to the teacher finally arrived he saw that he was the person that had refused to speak to him as he waited in the atrium. He was accepted as a student, which was quite extraordinary, as the Master had not wanted any new Aikido students during the period of the war, let alone a stranger! “

Marco Muccio, a close friend of one of Professor Mergè’s students, adds:

“The interesting thing is that the first Aikido training with Salvatore Mergè was held in Morihei Ueshiba’s home, with particularly exhausting exercises for the development of the Hara, and ukemi on pillows on the floor!”

Here’s a little more about Tada Sensei’s journey to Italy, from his essay “Founders of Aikikai d’Italia” (イタリア合気会を創った人々), published in the Aikikai’s “Aikido Tankyu” magazine:

One hears the words “the foreign expansion of Aikido”, but what I remember most are the bells and steam whistles that I heard at the pier in Yokohama and the farewell parties with O-Sensei at their center that surrounded my Sempai going abroad – Mochizuki, Tohei and Abe.

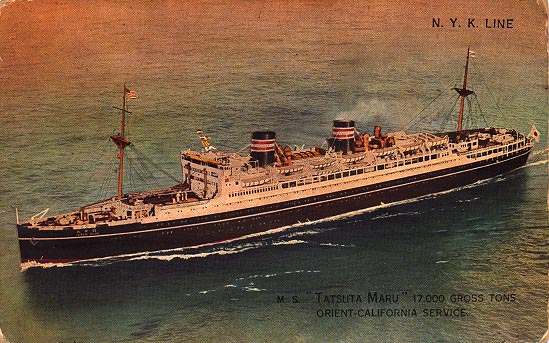

A postcard of the Tatsuta Maru – 1931

Of course I can’t reach back that far, and those memories may have overlapped with memories of tapes of my father’s trip abroad on the Tatsuta Maru in the beginning of the Showa era, but in spite of that I had vague thoughts at the time that someday I too would be going abroad.

That became a reality in Showa 39 (1964).

At that time, those going abroad specifically to spread Aikido had to do three things:

- Go alone.

- Go with a one-way ticket.

- Go without money, receive no allowance from their family, do no other part time work.

Keeping faithful to to “Haisui no Jin” (Translator’s note: 背水の陣 – the “fighting with one’s back to the river” strategy made famous by General Han Xin in the Battle of Jingxing), with $250 in my breast pocket I left my home in Jiyugaoka just as the Tokyo Olympics were in their final stages. My tentative goal was Italy, and from there I would travel through South America and then return home. It was an incredibly uncertain plan, but those were my expectations at the time.

Motokage Kawamukai in 2011

The first person to make the existance of the thing known as Aikido in Italy was Tadashi Abe (阿部正), who was active in France. Next were the sculptor Haru Onoda (小野田はる) and Mr. Kawamukai (川向), who had traveled to Rome as a tourist.

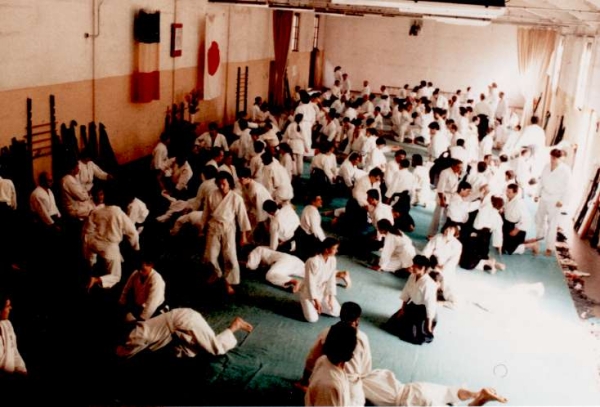

When I arrived in Rome I was introduced to a club at the Administration of the State Monopoly Autonomy (“Amministrazione Autonoma dei Monopoli di Stato”, the state monopoly on tobacco) which was run by Mr. Chierchini, and started training at that dojo. Six months later we had a demonstration at the National Police Academy, and then held a two month training session hosted by the Ministry of the Interior. This is how my Aikido life in Europe began.

The Italian Aikikai Hombu Dojo in Rome

Professor Mergè, who was a member of the Italian embassy during the war and entered Ueshiba Dojo, was in good health in Rome, and people who had heard him speak of Morihei Ueshiba Sensei at the school of Oriental languages at which he taught were quick to enroll. Through the introduction of one of these people, Mr. Serpieri, in later years we would be able to use one of the of the buildings designated as a national property as a dojo. It was surrounded in four directions by the ancient Roman aqueduct and castle wall, monuments, the military museum and the department of waterworks, and after nightfall it was a place where not a sound could be heard. This is now the Italian Aikikai Hombu dojo. I lived in one room at the bottom of the stairs there. The students called it “Sensei’s Grotto”.

A postcard of the Tatsuta Maru – 1931

A postcard of the Tatsuta Maru – 1931 Motokage Kawamukai in 2011

Motokage Kawamukai in 2011 The Italian Aikikai Hombu Dojo in Rome

The Italian Aikikai Hombu Dojo in Rome