I think you can see Doshu’s dilemma. He has to continue to teach the ‘essence’ of the art, but without knowing very much about what his grandfather actually did. He is a few years younger than I am and all he knows has been filtered via Kisshomaru and those deshi of Kisshomaru’s generation. Doshu’s son Mitsuteru will have an even bigger problem. Apart from a few exceptions like Tomiki and Tohei, Kisshomaru allowed the old deshi like Tada, Yamaguchi, Arikawa to get on and teach what they had learned from Morihei Ueshiba directly, in so far as they understood this. The variety was allowed to flourish, but with the passage of time there has been an inevitable dumbing down and an increasingly frantic insistence that what the Hombu is doing is the only means of aikido salvation. I think if the Aikikai could make the eight basic waza into sacraments, they would leap at the chance.

Former International Aikido Federation Chairman Peter Goldsbury

on “The Future of Aikido“

Some time ago, in 2015, Mark Murray allowed us to post the first part of his essay on the evolution and transmission of Aikido, “The Ueshiba Legacy“. In this essay he discussed the two legacies of Aikido – the legacy of the father, Morihei Ueshiba, and the legacy of the son, Kisshomaru Ueshiba. In Part 2 he now follows up that essay with a further discussion of these issues and how they have affected the art of Aikido as it exists today.

Mark is an “IT Specialist by trade and a writer by choice” (check out the Mark Murray Books website, and the Mark Murray author page on Amazon), but when he’s not doing either of those things he is usually training in the martial arts, and that is the context in which most of us are probably familiar with him.

The Ueshiba Legacy – Part 2

by Mark Murray

The Diverging Legacies of Ueshiba

Introduction: As I noted in a previous article, there are two Ueshiba legacies: Morihei Ueshiba and his son Kisshomaru Ueshiba. That article introduced some research into the fact that there are two different legacies. It did not go into any kind of detail on what those actual legacies were, nor did it go into any kind of peer-reviewed academic detail. I am not an academic. It is up to the reader to decide whether or not he/she finds the articles useful.

A: The Words

In the previous article, references were given from both pre-war and post war that what Ueshiba talked about was both mostly unintelligible and also not what was passed on via Kisshomaru Ueshiba. Father and son lived in two different worlds. Morihei Ueshiba lived the highlight of his life prior to World War II. Kisshomaru was greatly influenced by World War II.

- Kisshomaru Ueshiba

Imagine living during World War II. The people of two islands, half a world apart, experienced the same nightmare. In the United Kingdom between 1940 and 1941, Germany raided 16 British cities. London was bombed every night for 57 nights. Picture yourself in your home as night falls and the air raid sirens go off. The ground shakes, fire lights the sky. You run for an underground shelter, heart pounding. Screams echo in your ears from somewhere to your right. It takes forever to get to the shelter, your head down eyes focused on the ground as glimpses of your feet come into view from your outright run. Your chest starts burning and all your gasping for breath isn’t helping. But you make it. An eternity later, the sun rises and you emerge from darkened safety only to see entire blocks of the city have been flattened and some of the rest are still burning.

“Devastation from the Fires of the Shinjuku Commercial District,” 1945 photo by Kageyama Koyo of the aftermath of a

March 9-10 firebombing of Tokyo by the U.S. Air Force

Located around the world in Tokyo similar bombings were occurring. On March 9th 1945, the United States launched another firebombing attack. Kisshomaru Ueshiba, who is only 23 years old and barely out of university, is hardly an experienced, mature adult in this war-torn world. To make matters worse, Morihei Ueshiba turned over complete control of the Tokyo dojo to his son when Kisshomaru was 21 (*1). It is a miracle that the Tokyo dojo is still standing amidst the fires and ruins of the city. Five months later, all of Japan was brought to her knees when the United States dropped two atomic bombs. The unimaginable happened. Japan was defeated and surrendered. That was the fractured and ruined world of Kisshomaru.

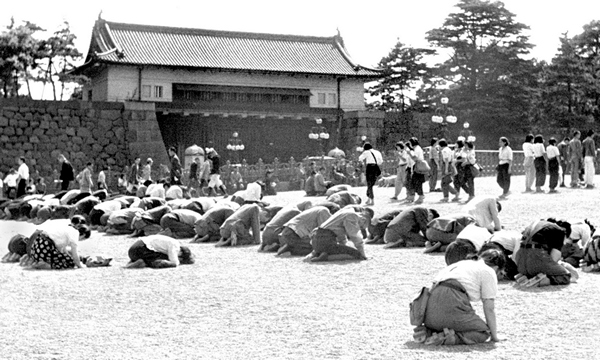

Japanese bow in front of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo

Japanese bow in front of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo

as they listen to Emperor Hirohito’s radio broadcast

announcing Japan’s surrender in World War II

Kyodo News Photo – August 15th, 1945

It was inevitable that Kisshomaru would strip most of his father’s words out of the aikido being created at Tokyo. From the ban on martial arts after the war to just having to survive, Kisshomaru strained to keep the Tokyo dojo going. Families were living in the building. Most students were just trying to make ends meet, let alone devote time to training. From this rubble, Kisshomaru created a new direction for aikido. He took out most of his father’s references to Omoto theology and introduced a training for spirituality, peace, and love. And why not? Most of the students had no clue what the old man was talking about anyway. The world had changed after the end of World War II. Japan was rebuilding. Kisshomaru started looking to the future.

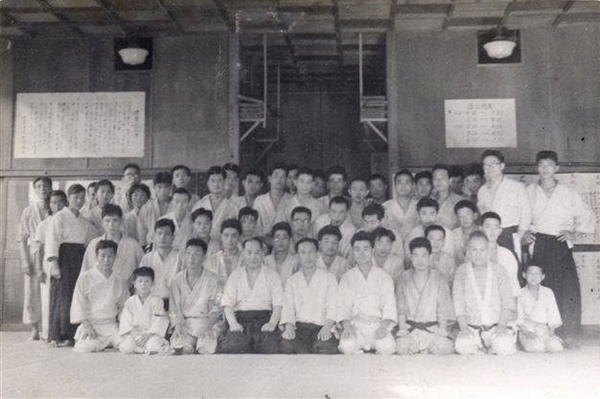

Aikikai Hombu Dojo around 1957

Aikikai Hombu Dojo around 1957

In back behind the doorway there were still war refugees living in the dojo,

after they left that area became the men’s dressing room.

Yasuo Kobayashi Sensei’s sister Fumiko standing at the far left.

With regards to words, the legacy Kisshomaru built was taken up by the entire world. People from all over started training in the aikido that was disseminated from Tokyo hombu. Millions of people flocked to this. The ideals that were transmitted were built upon changing the world for the better. The ideal of using an attacker’s attack against him/her in a loving, protective manner while there not being a winner/loser with the martial ability to carry it off was like going after the Holy Grail.

Seminar participants

Seminar participants

12th International Aikido Federation (IAF) Congress in Takasaki

September 27th – October 2nd 2016

Unfortunately, it was based upon Morihei Ueshiba’s martial abilities, which were not part of the legacy passed on by Kisshomaru, but this will be further detailed in another section. Make no mistake, Kisshomaru’s impact upon the world of aikido was huge. It brought together people from all over to train together in harmony, that probably would never have trained together. Almost fifty years after the death of Morihei Ueshiba, millions of people worldwide still train in aikido thanks to the words and ideals of Kisshomaru. It is a legacy that has fluidly changed and adapted over time yet, for the most part, still retains the look and feel of Kisshomaru’s vision. Many people will flock to Modern Aikido in the upcoming years as it has a legacy to thrive in a world desperately looking for peace and love.

- Morihei Ueshiba

Morihei Ueshiba used Omoto terminology to pass on his view of training aiki. But the secret, aiki, was never about the Omoto religion at all.

From André Nocquet:

No, Aikido is not a religion. One day I asked my master, Master Ueshiba, “You always say that Aikido is Love then, isn’t there a very narrow link with Christianity?” He told me, “Yes, there is a very narrow link with Christianity but if you go to Europe, never say that Aikido is a religion. If you practice Aikido well, you may become a better Christian but if a good Buddhist practices Aikido, he will also become a better Buddhist.” Aikido is a way, a path, it helps to better understand religions and philosophies, but it is not a religion, this is what he told me. (*2)

When we look at spiritual misogi, Seiseki Abe is a good example. Around 1952, Seiseki Abe says this about talking to Ueshiba:

“How did you ever learn such a wonderful budo”, and he answered, “Through misogi.” Now I had been doing misogi since 1941 and when I heard that Aikido came from misogi, suddenly “snap”, the two came together. (*3)

Seiseki Abe had been doing misogi for at least 10 years prior to training in aikido and wasn’t at all near Ueshiba’s skills or abilities, nor did he even see misogi and aikido as being similar. We can see from this that something that Ueshiba knew and had trained was the underlying basis for powering his misogi exercises.

To view the legacy of Morihei Ueshiba’s words, we have to go beyond looking at the Omoto religion. Omoto was not part of Morihei Ueshiba’s legacy. He used Omoto merely as a vessel for aiki training. What, then, did Morihei Ueshiba’s words mean?

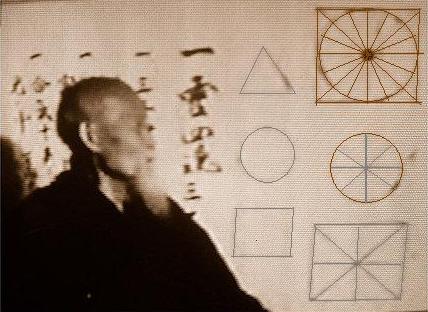

Morihei Ueshiba lecturing

Morihei Ueshiba lecturing

the text behind him reads “Ichirei Shikon Sangen Hachiriki”

From the translation on the Aikido Sangenkai website:

Aikido is the way of harmony, that is to say the living form of Ichirei Shikon Sangen Hachiriki, the form of the fabric of the universe, specifically the form of the High Plain of Heaven. (*4)

Ueshiba explained Hachiriki as The 8 powers are opposing forces:

Movement – Stillness, Melting – Congealing, Pulling – Loosening, Combining – Splitting / 9-1, 8-2, 7-3, 6-4 (*4).

These are 4 pairs of opposites.

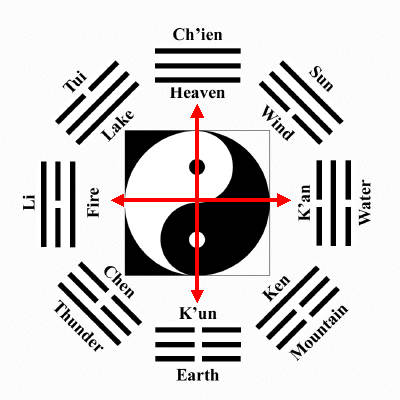

To understand just how important “opposites” are, when Henry Kono asked O-Sensei “Why can we not do what you do, Sensei?” the answer was quite simply “Because you don’t understand In and Yo.” (*5) Opposing forces.

As a bit of a sidetrack, Ueshiba was an avid reader of the Chinese classics. If we look at a portion of the Chinese Martial Arts, we find that opposing forces is the foundation of many. Taiji itself is about opposing forces.

“In the declining years of the Yuan Dynasty, there was a retired scholar called Zhang Sanfeng who took the basic Confucian principle of taiji and mixed it together with the major principles of the other schools of thought, putting the five elements and eight trigrams into his boxing techniques and footwork, using taiji’s passive and active, hardness and softness, movement and stillness, as metaphors for its function. With these as its main points, it became known as the internal school, distinct as a result from the external school.” (*6)

As noted from Brennan’s translation, there are opposing forces in passive/active, hardness/softness, and movement/stillness.

Chris Li notes the similarities between what Morihei Ueshiba says and the Chinese classics:

“So now we see that Morihei Ueshiba’s cosmology for the physical structure of the Universe is identical to the Chinese cosmology. Further, we see that Morihei Ueshiba’s structure for the physical manifestation of his art is identical to that used in the Chinese internal martial arts – right down to the terminology.” (*4)

Morihei Ueshiba talked about Izanami and Izanagi. He talked about kami, which was often written as ka (fire) and mi (water). He transposed deities for opposing forces. We can see that these opposing forces meant a lot to Ueshiba as he talked about them all the time. It is exactly this concept of opposing forces that is one of the foundations for aiki.

The In-Yo / Yin-Yang Trigrams showing

The In-Yo / Yin-Yang Trigrams showing

Morihei Ueshiba’s “Cross of Aiki“

We can tie in/yo or yin/yang or ka/mi or Izanami/Izanagi back to Daito ryu. There are various mentions of in/yo throughout Daito ryu. The concept can be traced back to Sokaku Takeda’s grandfather, Soemon:

“Soemon studied the arts of yin-yang divination (ommyodo) in Kyoto under the Tsuchimikado family, who were descendants of renowned diviner Abe no Seimei (921-1005), eventually receiving a menkyo (license of mastery) certificate and obtaining the title of Takumi no Kami. After returning to Oike in the Aizu domain he served as the chief priest of Aizu Ise Shrine and was known both as an expert in the Shinto religion and yin-yang divination and a master of Daito-ryu. He taught these arts in different places, and also transmitted secret teachings to the Aizu domain councilor Saigo Tanomo.” (*7)

The Heian Era practitioner of Onmyodo (“The way of Yin and Yang”)

The Heian Era practitioner of Onmyodo (“The way of Yin and Yang”)

Abe no Seimei, 921 – 1005

Portrait by Kikuchi Yosai, 1781 -1878

From Tokimune Takeda – son of Sokaku Takeda, and Soke of Daito-ryu Aiki Budo:

“In-yo Aiki-ho” fills the Seika Tanden with Ki through Kokyu-ho and strives to concentrate Ki-ryoku through mental concentration. Closing the five-fingers, inhaling quietly is called “In” (“Yin”), opening the five fingers strongly and exhaling is called “Yo” (“Yang”). Through the continuation of this breathing method the mind becomes clear, the vision becomes sharp, the “spirit”, “ki” and “power” are unified, a courageous spirit is developed, and especially – the various practical applications of the ten fingers of both hands gives rise to superhuman powers. (*8)

From Invincible Warrior by John Stevens:

Regarding Takeda, “His extraordinary ability was due to mind control, technical perfection honed in countless battles, and mastery of aiki, the blending of positive and negative energy.”

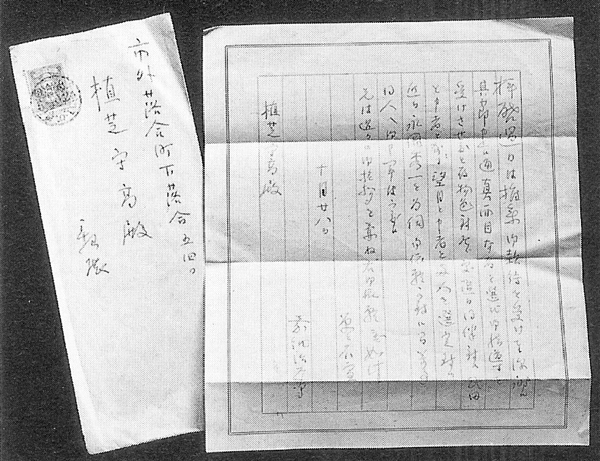

Letter from Jigoro Kano to Moritaka (Morihei) Ueshiba

Letter from Jigoro Kano to Moritaka (Morihei) Ueshiba

introducing Minoru Mochizuki and Jiro Takeda,

sent by the Kodokan to train at the Kobukan – October 28 1930

From “Aikido Kaiso Ueshiba Morihei-den” (合気道開祖植芝盛平伝)

According to Kisshomaru Ueshiba,

after meeting Morihei Ueshiba Jigoro Kano said:

これこそ私が理想していた武道、すなわち正真正銘の柔道である。

“This is my ideal budo, that is, genuine Judo.”

Finally, even Kano knew that the secret to budo was in/yo. Jigoro Kano visited Morihei Ueshiba to watch a demonstration of aikido. Kano was so impressed that he remarked that what he saw was what he considered an ideal budo. What did Kano view as an ideal budo?

Kano’s concept of Ju no Ri, was based upon the Taoist precept, “reversing is the movement of the Tao,” also described by the statement “the most yielding things in the world overcome the most unyielding.” Kano combined Ju no Ri with the interplay of forces as defined by the precept of in-yo (yin and yang, hardness and softness, negative and positive, receptiveness and resistance), and used the following to explain his concept of Kuzushi founded on Ju no Ri. (*9)

Like the Japanese changing yin/yang to in/yo, Morihei Ueshiba changed his Daito ryu roots of in/yo to many various other phrases, such as ka/mi, Izanami/Izanagi, etc. Ueshiba’s legacy of words was using Omoto terminology to talk about aiki training that he received from Sokaku Takeda. Aiki is the body changing method which allowed all the greats like Takeda, Ueshiba, Sagawa, Horikawa, etc to stand out. Morihei Ueshiba talked about in/yo, ka/mi, heaven/earth/man, standing on the bridge, etc and all of these ideals point to internal martial training methodologies.

This was Morihei Ueshiba’s legacy of words that Modern Aikido from Kisshomaru Ueshiba did not transmit. Those reading Morihei Ueshiba’s words and who have the understanding of those internal concepts to implement them in physical training have the basis to keep his legacy alive and thriving.

(1) http://www.aikiweb.com/forums/showthread.php?t=25175

(2) http://www.guillaumeerard.com/aikido/interviews/interview-with-andre-nocquet-8th-dan-pioneer-of-aikido-in-europe

(3) Aiki News Issue 045

(4) https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/aikido-structure-universe/

(5) “Aikido Memoirs” by Alan Ruddock

(6) https://brennantranslation.wordpress.com/2012/08/27/the-taiji-manual-of-xu-yusheng/

(7) http://www.daito-ryu.org/en/prior-to-the-19th-century.html

(8) https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/sagawa-yukiyoshi-masaru-takahashi-breath-training-daito-ryu/

(9) http://www.aikidojournal.com/?id=2138

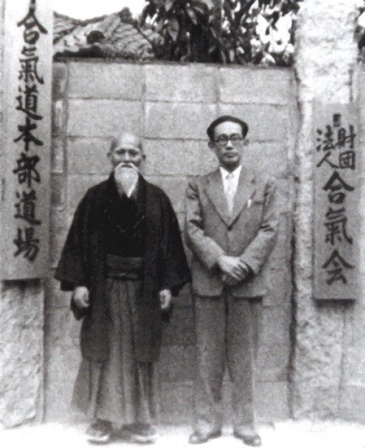

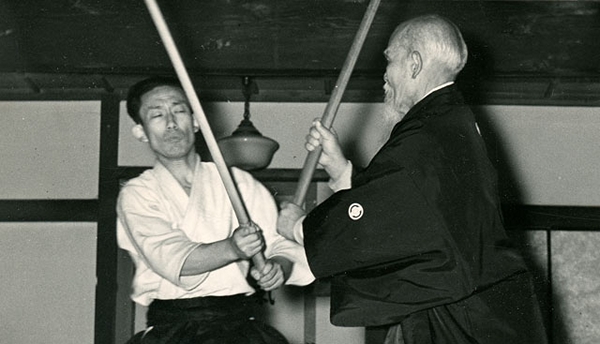

Morihei Ueshiba and Kisshomaru Ueshiba

Morihei Ueshiba and Kisshomaru Ueshiba

at the old Aikikai Hombu Dojo around 1957

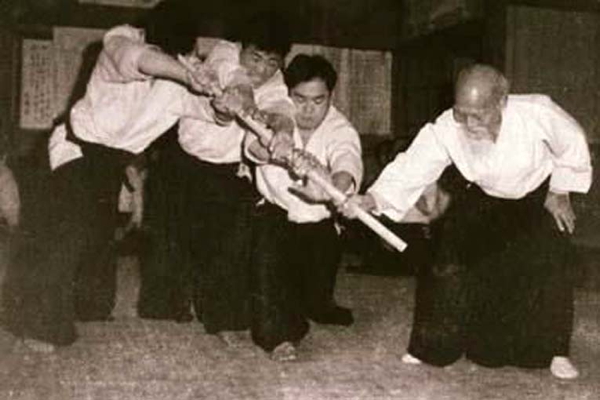

B: Weapons

Weapons in Modern Aikido are a mess. Koryu people smile, are polite, but they, too, think Modern Aikido weapons are, well, not really using weapons. This is a very important divergence from Morihei Ueshiba’s reputation.

Meik Skoss eloquently states about Modern Aikido weapons:

That’s because they know squat about weapons. Sorry to be a little heavy again, but I’ve done an awful lot of aikido (sigh… wish now that I’d done more judo and/or classical jujutsu — *that* is real “aiki”) and trained a lot of places (North America, Southeast Asia, and Japan). I have got to say that there’re very, VERY few aikido teachers, in any of these places, who have half a clue about using weapons. It is pretty hard to believe, but they don’t even know the TGIF Principle (in relation to the kissaki), when doing tsuki waza. That seems to be an awfully basic concept to me, but, noooo-o-o-o… (*1)

- Kisshomaru Ueshiba

Peter Goldsbury notes:

I think the influence of Koichi Tohei in the early postwar years of the Aikikai Hombu should not be underestimated. I have it from shihans who were not smitten with Watergate-style amnesia that many of the sword and jo kata originally practised by postwar deshi came via Tohei Sensei. (*2)

Most of the weapons katas from Modern Aikido were created by post war shihan from various experiences outside of training with Morihei Ueshiba. There are many sources to uphold this. (*3) (*4) (*5) (*6)

Tamura Nobuyoshi was asked, “Did O’Sensei also practice tanto dori?”

He answered:

I never saw him do it. Back in the day the Yakuza always fought with a knife. One day a fighter asked what one could do against these types of attacks. It was the sempais who developed this work. It was very spectacular for the demonstrations.”(*7)

Tanto work was created entirely by Modern Aikido.

Tamura Nobuyoshi was also asked, “Was it O’Sensei who created the katas such as Ichi no Tachi?” He answered, “These are the creations of Saito Sensei. O’Sensei showed the shochikubai ken but did not teach katas as such.” (7)

Meik Skoss notes this:

After WWII, Hikitsuchi and Saito stand out as well-grounded in weapons training. Other teachers, such as Tamura, Chiba, Kanai, and Saotome appear to have gotten most of their buki waza from other sources. (*4)

The aikido ken, jo, and tanto kata are creations of those shihan from Modern Aikido. Most of them created their weapons kata outside of any of Morihei Ueshiba’s teachings. The legacy of Modern Aikido has been to create weapons kata from various sources to add to the curriculum. Unfortunately, this is the weakest spot in Modern Aikido. Those in koryu think very little of aikido’s weapon work and they have very valid points. One can certainly understand Kisshomaru’s hesitancy to train weapons in Tokyo.

- Morihei Ueshiba

From Meik Skoss:

Did Ueshiba Morihei formally study a lot of the koryu? No, not too much. A little Tenjin Shinyo-ryu, a bit of Yagyu Shingan-ryu, a fair amount of Daito-ryu. That’s all that people’ve been able to document with any degree of certainty. (*1)

Meik Skoss also made this comment:

To the best of my knowledge, Ueshiba’s work with weapons drew on a number of technical sources, but was primarily a rather idiosyncratic style that he employed for personal training rather than an organized system. He’d demonstrate a number of applications from time to time, but that was to illustrate the principles of the art rather than to “teach” buki waza per se. For the most part, by all accounts, most of Ueshiba’s post-war students did not receive systematic instruction in sword, staff, or stick. Amongst his students of pre-WWII vintage, probably Shirata Rinjiro (sword) and Iwata Hajime (staff) are probably the premier examples. (*4)

Tamura Nobuyoshi was asked, “What was the shochikubai no ken?” He answered, “Shochikubai no ken is not a specific form. The movements of O’Sensei varied according to his mood.” Nobuyoshi was also asked, “Did O’Sensei not teach paired katas, whether at Iwama or Hombu dojo?” He answered, “No.”

Diane Skoss notes this about jo kata from Tomiki aikido:

I’ve done the solo jo kata in Tomiki aikido (when in Japan–hm, maybe I did it in the States too?) and it is indeed closely related to one of the Ueshiba jo kata (can’t remember which one though). We all did it in Tokyo, so I wonder if the source might not have been Tomiki S. or Ohba S, rather than Nariyama S. I also have experience in both jukendo (5th dan) and JAA aikido (4th dan). There’s no question, in my opinion, that the yari/jo techniques are derived from bayonet. In fact, I asked Shishida S. about it one time and he confirmed that he had been told that (by Ohba S.? by Tomiki S?–it’s undoubtedly in my notes somewhere). I was also told that the choice of yari, for the Tomiki kata, was due to the fact that a spear (or jo) was more politically correct than a mokuju/bayonet. If you’ve got access to a mokuju, just try the techniques and see how much more sense the distancing makes. (*5)

I think we can see that both legacies, Morihei Ueshiba and Kisshomaru’s Tokyo hombu never really had the solid background in weapons that one would see in a koryu. What is known about Morihei Ueshiba is that he used a bayonet, a spear, a shortened spear, and a bokken. Even when he had a jo in his hands, it was used more like a spear or bayonet than a jo. Modern Aikido does not have kata for spear or bayonet. Two diverging legacies.

“The jo he used was the length of a regular jo,

“The jo he used was the length of a regular jo,

but it was sharpened at one end.”

A Day in the Life of the Founder Morihei Ueshiba, April 1968

by Gaku Homma

Because Ueshiba’s training in weapons was eclectic and his teaching was eclectic, the main legacy he left for those following his footsteps was just to use aiki when wielding a weapon. He would watch kata and say, With aiki, we’d do it this way. The divergence with Kisshomaru Ueshiba’s Modern Aikido was that aiki, more specifically Daito ryu aiki, was left out.

The legacy of Morihei Ueshiba was to use weapons as an extension of his aiki body. Daito ryu aiki must be present for anyone wanting to follow in Ueshiba’s footsteps.

(1) The old fa.iaido Google group dated 2/12/99

(2) http://www.aikiweb.com/forums/showthread.php?t=15066&page=4

(3) http://www.aikiweb.com/forums/showthread.php?t=15066&page=5

(4) http://www.e-budo.com/forum/showthread.php?773-origins-of-aiki-jo

(5) http://www.e-budo.com/forum/showthread.php?773-origins-of-aiki-jo/page3

(6) The old iaido-l archives

(7) Interview with Tamura Nobuyoshi, by Leo Tamaki

(8) https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/aiki-is-love-isnt-it/

C: Aiki

- Kisshomaru Ueshiba

Kisshomaru had an extremely hard decision to make regarding Tokyo. His father had left him in charge. He was living in the shadow of a famous man. He couldn’t do what his father did. He didn’t have the skill and he didn’t have the love of martial arts. At least in the beginning, he didn’t want to do aikido. The burden placed on him by his father forced him to take an active role in aikido.

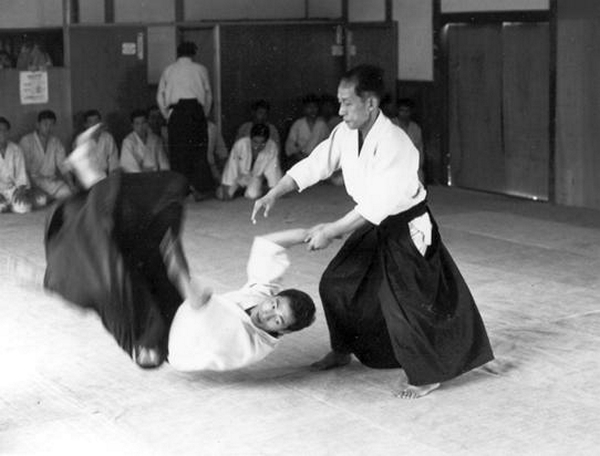

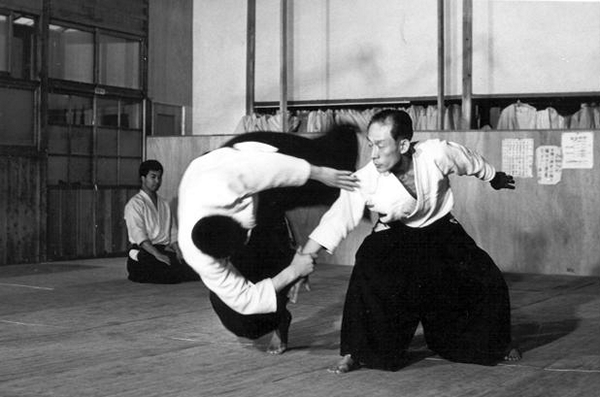

Kisshomaru Ueshiba at Aikikai Hombu Dojo in 1967

Kisshomaru Ueshiba at Aikikai Hombu Dojo in 1967

After the war, there were families living in the dojo, the roof was leaking, and many people were barely surviving. Kisshomaru’s strength throughout these tough days cannot be underestimated. Not only did he survive, but he repaired the dojo, brought in students, and the families were relocated. Of course, post war Modern Aikido was not a creation by just Kisshomaru. There were many people who helped him keep Tokyo going. As a famous example, Koichi Tohei was also in Tokyo and contributed greatly to the training there. Kisshomaru was the center that held them all together. He was the son of Morihei Ueshiba. For many, the chance to train with Morihei only came through Kisshomaru.

Kisshomaru knew that he couldn’t spread aikido to the world using his father’s words. He took most of the unintelligible babble out. He knew that if one wasn’t famous or technically “strong”, one had to replace it with something. A codified system of techniques was created. Public demonstrations were introduced, even though Kisshomaru was frightened of his father’s rage initially. However, Morihei allowed his son to change things. This is important to note. Morihei gave Tokyo to his son and allowed his son to make changes. In Tokyo, Kisshomaru also had many different personalities to deal with, so a sort of “hands off” approach to training outside Tokyo was taken. This allowed a specified training to occur in Tokyo but yet give people enough room to grow so as not to stifle them.

Frank Doran mentions that Tohei created many energy games and practices. (*1) Patrick Augé states:

Mochizuki Minoru Sensei said that when he was studying with Ueshiba Sensei (late 1920’s), robuse was the name given to the technique that later became Ikkajo, then Ikkyo after the war. The present ikkyo as taught by most Aikikai (and Aikikai related) teachers is the result of the modifications made by Tohei and Kisshomaru Sensei in order to simplify Aikido and make it available to more people…. (*2)

Stan Pranin notes that Kisshomaru Ueshiba gradually changed the technical syllabus and created a flowing style technique based system. (*3) Koichi Tohei was head instructor for many years and his teaching was influenced by the Tempukai. (*4) Morihiro Saito also makes note of some of the things that Koichi Tohei introduced into Modern Aikido training. (*5)

Peter Goldsbury touches upon these things in an Aikiweb post:

There are many subjective accounts of how Morihei Ueshiba trained and what he taught, but I do not think that these accounts allow us to state categorically that this or that was how Ueshiba taught or trained. Apart from Doshu, who I think is in a special category, the Hombu instructor with whom I have discussed these issues the most is Hiroshi Tada. Like Tohei, H Tada was a student of Tempu Nakamura, but he seems to have been very careful as to what he taught in the Hombu and what he taught in his own dojo and in Italy. In other words, he seems to have accepted the idea that only certain things were to be taught or practiced in the Hombu, but also that the other things were to be practiced elsewhere. He teaches weapons in Italy, but never in the Hombu, and when I mentioned some details of a certain jo kata that I practiced in Italy to another Hombu instructor, he was very curious and wondered where Tada had learned it. Like other older Hombu instructors, Tada sets great store by solo training exercises and these seem to consist mainly of kokyu exercises of increasing sophistication and complexity. But he has never taught anything like pushing hands etc and I suspect that the occasion for seeing the results of all this kokyu training would be in basic aikido waza, like shoumen-uchi 1-kyou. This issue for me is which bit of Tada’s training comes from Nakamura and which bit from Ueshiba — and whether he could make such a distinction. Add to this Ellis Amdur’s theory of Ueshiba’s use of his students as ‘crash-test dummies’ and you also have to entertain the possibility that he showed different things to different students — and he showed this by having them take ukemi. You also have to entertain the possibility that the skills that Ueshiba possessed which could be interpreted as IP skills could be acquired by Ueshiba’s students in various ways, but not necessarily from Ueshiba himself by a direct transmission.

and

I am not sure that acceptance is the right word here. Sufferance might be more appropriate. One of the yudansha who trains with the group I look after in the Netherlands attends the workshops of Dan Harden and Minoru Akuzawa when they come to Europe. His aikido comes from another source, of course, but on one occasion a senior Hombu instructor stopped and asked him, “Why are you so strong?” The question was not meant in a negative sense at all and he was not talking about physical strength. The instructor knew exactly what he was seeing and I believe the older generation of instructors in Japan also know this. But, as you say, this knowledge is clandestine and limited to individuals. These individuals are in the Aikikai, but are dwindling in number. Yamaguchi, Tada and Arikawa used to visit our dojo regularly and I once asked an instructor why Doshu (the present Doshu, not Kisshomaru) was never invited. This was a few years ago and the answer was quite blunt: “He’s too young and does not know enough.

I think Doshu is an active exponent of a certain interpretation of iemoto, but the great danger here is that aikido is not a koryu and does not have kata in the sense understood in a koryu. There is a sense that the waza can be seen as vehicles for the expression of creativity and this, to my mind, is what Morihei Ueshiba meant by Takemusu Aiki. He always showed waza, as did Takeda Sokaku, but seems to have presented them slightly differently to different deshi. So creativity can be understood in many ways. Unlike the present generation of Japanese martial arts exponents, Morihei Ueshiba also read the Chinese classics and was familiar with all the texts that are the foundation of Chinese internal arts. Recently I came across a scholarly work on yin-yang and its place in Chinese thought and culture. Even a quick read was enough to show that this is a complex and multi-faceted concept. We all know the question that a student asked Morihei Ueshiba and his answer, citing the knowledge of yin and yang. Ueshiba did not give any further explanation and left it to the students to grasp what he meant. The point is that he was probably familiar with the whole breadth and depth of the concept, but his students did not share this familiarity. (*22)

In the end, Tokyo became a technique driven center of aikido. Kata was emphasized where Morihei Ueshiba said his aikido was formless. Ranks were inflated to send newly created shihan out into the world to spread Modern Aikido. A worldwide message that aiki was harmony, peace, and love spread. While some of this was misconceptions from foreign students who clamped onto the whole spiritual love everyone idea, Kisshomaru knew that to hold the center, some of the fringes had to be given a bit of leeway. The definition of aiki started to become a living, morphing identity which swirled around the peace and harmony message. In/yo, or as Ueshiba would write ka/mi, was solidly pushed to the side. This then, was where the two legacies diverged. Spiritual harmony became prominent with a focus on techniques. Daito ryu was removed as much as possible, including the secret of aiki from Daito ryu. Given the state of Japan after the war, the state of the entire world after the war, and Kisshomaru’s onus put upon him by his father to hold Tokyo with his life, it is certainly an extremely worthy legacy that Kisshomaru created. While it was never the same as his father, Morihei Ueshiba was proud of what his son had accomplished.

- Morihei Ueshiba

Morihei Ueshiba tested his aiki body by using push tests. These tests were outside of using techniques allowing Ueshiba to demonstrate the secret of aiki. When Tenryu met Ueshiba, Morihei talked about how he watched Tenryu waste his strength trying to unsuccessfully push him over as he was seated. Ueshiba even lets Tenryu try to push him over by pushing on his forehead. Tenryu can not. Ueshiba pushes his legs outward but Tenryu still can not push him over. (*6) From another article, Ueshiba explains that the reason Tenryu couldn’t push him over is because he knew the secret of aiki. (*7) In an interview with Tenryu, Ueshiba gave Tenryu his left wrist and allowed Tenryu to do anything with it. Tenryu could do nothing and mentions that grabbing Ueshiba’s hand felt like grabbing an iron bar. Even when Tenryu lunged at Ueshiba, Tenryu could not get the better of him. (*8) Tenryu tried to push or pull Ueshiba, but could not budge him. (*9) (*10) Tenryu was over six feet tall and weighed over 240 pounds. (*11) Remember, Ueshiba states that he could not be moved because he knew the secret of aiki.

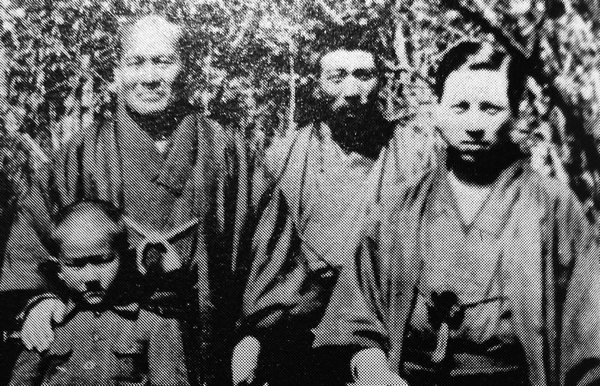

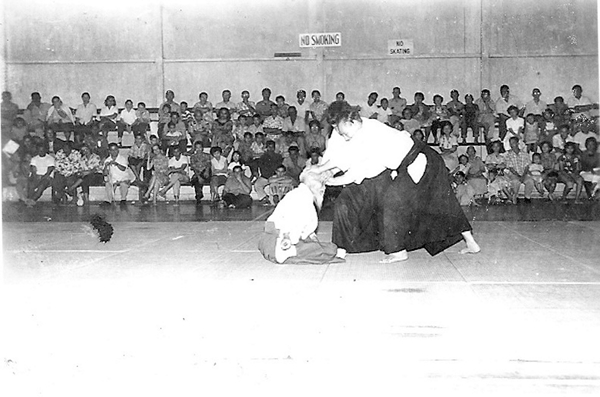

Morihei Ueshiba demonstrating a push-test in Hawaii, 1961

Morihei Ueshiba demonstrating a push-test in Hawaii, 1961

with Yukiso Yamamoto and Nobuyoshi Tamura

In an interview with Hidetaro Nishimura (who introduced Kenji Tomiki to Morihei Ueshiba), Nishimura remembers Tenryu’s words about trying to push Ueshiba from behind and it was Tenryu who slid backwards. (*12) Notice that Tenryu is not a small man. He was a sumo wrestler who was tall, muscular and heavy. Yet, his training, his physical strength, and his solid build failed him in trying to push Ueshiba over. Aiki is not about physical strength, nor timing, nor body placement. Ueshiba was sitting and not moving. There was no timing or body placement involved.

“However hard we pushed the staff would not move.” – Yasuo Kobayashi

“However hard we pushed the staff would not move.” – Yasuo Kobayashi

In an article in Aikido Journal, Stan Pranin mentions Ueshiba having people push on a jo and also having people push on him while he’s sitting on the mat. (*13) Shirata talks about a time when he and about nine others pushed on Ueshiba. Instead of Ueshiba moving, those pushing slid backwards. (*14) Takafumi Takeno talks about starting his aikido training and Ueshiba was having his students push and pull him. Ueshiba remained unmoved. (*15) Seishiro Endo recounts a time when Ueshiba had Endo push on his knees from the side. Endo mentions that Ueshiba felt soft and like a void that sucked up the efforts to push. (*16) Kazuaki Tanahashi is on video talking about trying to push Ueshiba. It was a common occurrence. Tanahashi mentions that Ueshiba even had Saito trying to push him over. (*17) Gaku Homma talks about how near the end of his life, Ueshiba would still have students push against him. Homma also states that they could not push Ueshiba over. (*18) Robert Frager recounts his time with Ueshiba. Ueshiba had Frager put his hands together and then Ueshiba placed one of his hands on Frager’s top wrist. Frager tried to push Ueshiba’s hand but could not. (*19) When an interviewer asked Kenji Shimizu about what left an impression while training with Ueshiba, he replied:

Well…there were so many things that left an impression on me…I don’t know where to start. One day he said “Shimizu, are you free?”, and when I answered “Yes” he sat down in a backless chair and said “My back is tight, could you massage it a little?”. At the beginning, when I pushed on his back lightly, he said “What’s this? You don’t have any strength – push harder!”, so I put more strength into it and pushed on his back strongly but O-Sensei didn’t move at all. He just said “Push harder!” so I added even more strength and pushed on his back, but he didn’t move, not an inch. He was the same during training – O-Sensei would hold up his te-gatana (手刀) in kamae and say “OK, try pushing me!”. In any case, no matter how much of a master one is, he was of such an advanced age that one would think that he would fall over if pushed strongly. However, since he would become angry if we pushed lightly we would push with all of our strength. Even so, he wouldn’t move, not an inch. (*20)

Modern Aikido removed push tests as they required an aiki body to successfully accomplish them.

Something else to consider regarding Ueshiba’s legacy of aiki is that Morhei Ueshiba would twirl a short stick, sometimes a shortened spear, around and around. This was Kagura-mai, or Dance of the Gods. (*8) Ueshiba was showing a very important aspect of an aiki body in his movements. So important that he used it as an explanation at the 1955 shihan training session:

The 1955 shihan training sessions in Tokyo began with O-Sensei wielding a Jo in “Kagura Mae” (神楽舞 / “Dance of the Gods”). When questioned about technique during the training sessions O-Sensei would just repeat the “Kagura Mae” without saying a word.” (*21)

Ueshiba’s Kagura-mai is not found in Modern Aikido even though Ueshiba commonly showed this movement. This cannot be stated with enough emphasis, the Kagura-mai was an extremely important aspect for Ueshiba. Anyone wanting to follow Morihei Ueshiba’s legacy of aiki must understand it. Aiki was about changing the body. Ueshiba twirling the stick was showing an internal concept from an aiki body.

Kagura-mai, the Dance of the Gods

Kagura-mai, the Dance of the Gods

Peter Rehse notes:

Just be coincidence there was a biography of Hideao Ohba written by Shishida posted by Eddy Wolput as part of his study group today. Maybe he will repost it here but there were several interesting statements. “Ueshiba’s teaching method, which required students to learn with their bodies, obviously would not appeal to educators or to the world of predecessor arts like Judo and Kendo which employed rational, systematic teaching methods.” (*23)

There are pictures and descriptions of Ueshiba stabbing a tree with a spear. Interviews talking of nightly training sessions. Ueshiba had his students push him up steps, stating it was a valuable training method. There are many such examples Ueshiba used which were not kept by Kisshomaru. Modern Aikido did not follow the same training methodology that Morihei Ueshiba used. Kenji Shimizu noted this diverging training when he stated about Morihei Ueshiba:

When I was actively practicing there he often came and went. When he showed up everyone immediately sat down. At first, I thought that people were being courteous toward him. However, it wasn’t only that. It was also that the practices we were doing were different from what O-Sensei expected us to do. Once he lost his temper at us. No one realized that he had come and he shouted: “What you people are doing is not aikido.” (*20)

For those who think that Morihei Ueshiba only talked of spiritual mumbo jumbo that confused his students, it’s known that Ueshiba did teach internal training methods in a clear and concise manner. No ka/mi, no Izanagi/Izanami, but clear and concise on a specific exercise for what one needed to do to train aiki. It was something not found in Modern Aikido. But, as Peter Goldsbury has noted, “this knowledge is clandestine and limited to individuals.”

(1) Aiki News Issue 010

(2) Yoseikan NA website

(3) http://www.aikidojournal.com/encyclopedia?entryID=720

(4) Aikido Journal Issue 112

(5) Aiki News Issue 088

(6) Aiki News Issue 019

(7) Aiki News Issue 019

(8) Aiki News Issue 023

(9) Aiki News Issue 025

(10) Aiki News Issue 049

(11) Aiki News Issue 076

(12) AikiNews Issue 087

(13) Aiki News Issue 044

(14) Aiki News Issue 063

(15) Aiki News Issue 099

(16) Aikido Journal Issue 106

(17) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JpWY58LWaRE

(18) http://www.nippon-kan.org/abroad/scotland/sensei_ki_scotland.html

(19) Yoga Journal March 1982

(20) https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/interview-aikido-shihan-kenji-shimizu-part-1/

(21) https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/sadao-takaoka-meeting-osensei/

(22) http://www.aikiweb.com/forums/showpost.php?p=336927&postcount=87

(23) http://www.aikiweb.com/forums/showpost.php?p=346204&postcount=21

D: Morihei Ueshiba’s legacy detailed.

Ueshiba left a legacy. He stated that you didn’t have to be in a specific religion, but that aiki would complete it. When asked what aiki was, he answered, “I am aiki”. When he used spiritual terms, they were references to in/yo, which is the foundation for aiki. It was his vision to pass on aiki also known as Daito ryu aiki. There were a few students that he gave direct transmission to, most of them are known as the pre-war greats. Some of those students were around after the war.

Rinjiro Shirata (back right) at the Kobukan, 1931

Rinjiro Shirata (back right) at the Kobukan, 1931

How does one recognize that legacy of aiki? As just one example, a student of Rinjiro Shirata kept true to Shirata’s vision and from that, Ueshiba’s legacy. This student, Allen Beebe, was always searching for the meaning to what he had learned from Shirata. He recently started a website devoted to his years of hard work and effort. One specific article is worth reading to start the journey:

When I did take a peek I began to notice that the things that Dan was talking about, were things that I recognized. This happened often enough that I had the strong suspicion that Dan’s background relating to the topics discussed was almost definitely Daito Ryu. What he talked about and how he talked about were simply to “close to home” to be a fluke. (*1)

He goes on to state:

In the mean time, in the “early days,” it seems that most individuals were not coming to the same conclusions that I was. This, however, did not surprise me in the least. How could they? The majority of Aikidoshi, and even Daito Ryu practitioners for that matter, were completely unaware of most of what he was talking about. They had no frame of reference for comparison. It was as if Dan was speaking about infrared before it was commonly known. (*1)

Allen has started posting some of Shirata’s writings, ideas, and words. Ueshiba to Shirata to Beebe. Beebe then had his training methodology reinforced via a lineage of Daito ryu. The legacy of aiki. Ueshiba’s Daito ryu aiki.

(1) https://trueaiki.com/2017/02/20/how-i/

Published by: Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI

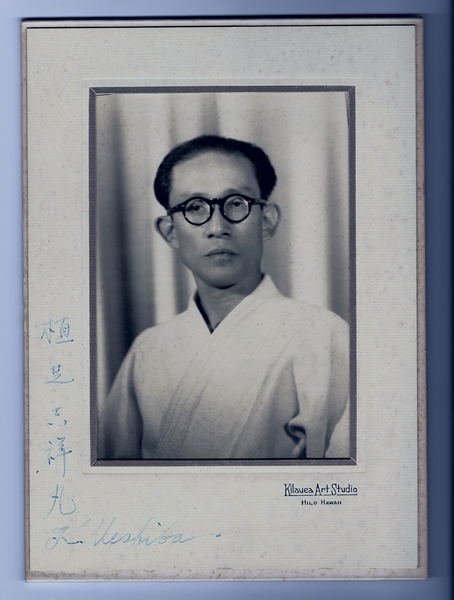

Kisshomaru Ueshiba with his father Morihei Ueshiba

Kisshomaru Ueshiba with his father Morihei Ueshiba Aikikai Hombu Dojo Aikido Shimbun – January 1999

Aikikai Hombu Dojo Aikido Shimbun – January 1999 Kisshomaru Ueshiba in 1963

Kisshomaru Ueshiba in 1963 Kisshomaru Ueshiba in Hawaii

Kisshomaru Ueshiba in Hawaii Kisshomaru Ueshiba’s wedding in Iwama

Kisshomaru Ueshiba’s wedding in Iwama Morihei Ueshiba and Kisshomaru Ueshiba

Morihei Ueshiba and Kisshomaru Ueshiba Kisshomaru Ueshiba at the old Aikikai Hombu Dojo

Kisshomaru Ueshiba at the old Aikikai Hombu Dojo

![El Legado de Ueshiba – Parte 1, por Mark Murray [Spanish Version]](https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/wp-content/media/kisshomaru-morihei-tohei1.jpg)

Japanese bow in front of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo

Japanese bow in front of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo Aikikai Hombu Dojo around 1957

Aikikai Hombu Dojo around 1957 Seminar participants

Seminar participants Morihei Ueshiba lecturing

Morihei Ueshiba lecturing The In-Yo / Yin-Yang Trigrams showing

The In-Yo / Yin-Yang Trigrams showing The Heian Era practitioner of Onmyodo (“The way of Yin and Yang”)

The Heian Era practitioner of Onmyodo (“The way of Yin and Yang”) Letter from Jigoro Kano to Moritaka (Morihei) Ueshiba

Letter from Jigoro Kano to Moritaka (Morihei) Ueshiba Morihei Ueshiba and Kisshomaru Ueshiba

Morihei Ueshiba and Kisshomaru Ueshiba “The jo he used was the length of a regular jo,

“The jo he used was the length of a regular jo, Kisshomaru Ueshiba at Aikikai Hombu Dojo in 1967

Kisshomaru Ueshiba at Aikikai Hombu Dojo in 1967 Morihei Ueshiba demonstrating a push-test in Hawaii, 1961

Morihei Ueshiba demonstrating a push-test in Hawaii, 1961 “However hard we pushed the staff would not move.” –

“However hard we pushed the staff would not move.” –  Kagura-mai, the Dance of the Gods

Kagura-mai, the Dance of the Gods Rinjiro Shirata (back right) at the Kobukan, 1931

Rinjiro Shirata (back right) at the Kobukan, 1931