Below is an interview that originally appeared on Nick Porter’s The Way You Practice blog. Following the English interview is a translation in Spanish by Juantxo Ruiz.

Hey folks! What follows below is an interview with Chris Li, a martial artist who has primarily trained in Aikido. He’s a great resource within the Aikido community regarding the history of the art and a very approachable guy. He also trains in “internal power”, which is something that never made sense to me, even when I trained Aikido. At best, it seemed like an overly complicated explanation of biomechanics. At worst, it looks like straight up woo-woo.

So rather than continue to flame online, I decided to ask someone in the know, and Chris was gracious enough to take some time and attempt to explain it to me. Perhaps I’m just a bad interviewer, but I’m still not sure I get it. What do you all think? Is there something to Internal Power training? Is it useful for martial artists?

Chris Li (CL) has been training in Aikido since 1981, and has also trained in Judo with a former coach of the Japanese and US Olympic teams and in Shito-ryu Karate, as well as several lineages of Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu. He spent some 15 years living, training, and teaching in Japan. He has been training with Dan Harden, in his Sangenkai organization, since 2010.

Nick Porter (NP): Thanks for taking the time to talk to me about this. I’ve always been fascinated with the idea of “internal power” but the actual practice vs preach seemed a difficult sell to me. To start, so that we’re on the same page can you define what you mean when you say “Internal Power?”

CL: Sam Chin once said to me “the thing about internal power is that… it’s power. ” And he’s right, the division between internal and external methods is a largely artificial way of classifying generally different methods of body usage. But they’re all power, they all involve the mind, the body and all the rest. On the other hand, playing the violin and power lifting are also both purely physical tasks that involve the same body and the same musculature but end up in very different places, so there are things that can be very different and yet involve some or all of the same elements. All sports use both strength and endurance, but of course we often divide physical conditioning into areas such as endurance exercises and strength building as a matter of convenience. So the internal / external dichotomy is artificial, of course, but it’s also convenient.

When I talk about internal methods I am talking about methods that, generally speaking are referring what is happening within the frame of my own body (rather than, say, a technique that is defined by what happens relative to another person’s body). Further, the methods I’m talking about are largely intent driven. Of course, everything’s intent driven, but the emphasis on intent in internal methods is often that you’re attempting to use or condition your musculature in a way that is generally different from the that you normally use it.

NP: Do you feel there’s a disconnect between the way Internal Power is explained (vs, say, the mechanics of tai chi or yoga) and the way it’s practiced such that more people don’t see a reason to begin training it?

CL: The descriptions are often difficult because they don’t make much sense without hands on. So yes, that can be a problem. IMO, it’s one of those things that has to be felt. People who join us and end up staying usually do so because we’re doing what they were looking for in the first place. In other words, they’d done the research on their own and had an idea of what to expect. But it may be that the difficulty of this type of training precludes, in part, an easily understood short description. Further, there’s no common frame of reference with most folks the way there is if I were talking about, say, baseball.

NP: I actually had a great discussion with some IP folks yesterday about that– how “it had to be felt” and “it just can’t be understood” are tough sells in the modern world. Is there a way you think IP could make itself more understandable?

Additionally, my other question for them (and now for you) is: how do you sort out someone who knows what they’re doing from a woowoo artist? All I’ve heard is

- A real IP master is exceedingly, overwhelmingly rare

- I definitely know one, though.

So in a system that’s very subjective (“you just have to feel it”), how can you know what you’re feeling is actual “power” instead of the power of suggestion?

CL: If you can think of a way to make it more understandable then I’m open to suggestions! I suppose that we really need an “elevator speech”, but part of the difficulty is that these things really are quite different. And that brings in the frame of reference problem that I mentioned above.

How do you tell? Well, that’s difficult too.

Experience with multiple folks certainly helps, so does intellectual honesty. In the end, I guess that you have to make your best judgement and take your chances.

Traditionally, I guess that you’d challenge an instructor and see what happens, but those kinds of things don’t always turn out well…

I’d also have to say that defeating or not defeating a particular person doesn’t necessarily say much about the method or theory. Everybody wins and loses when you roll.

NP: I think IP could take a few things from yoga. The way I see it, movement is movement and at its core, efficient movement is simple movement. This video of Kyuzo Mifune illustrates that point. I understand that his partners are giving him some respect. Even with that in mind, and with the understanding that I know nothing about Judo, I can understand and respect how he’s moving because how he’s moving seems logical, simple, and efficient. I contrast that with a lot of the IP videos I watch: where an uke grabs for their life, gets twisted around, then gets chucked across the room as everyone looks on in amazement. At its best, it seems like suggestion and a very compliant partner. At its worst, it starts looking like the no-touch KO people.

The thing I hate about the “it has to be felt” argument is that it’s self-fulfilling and, too often, the uke is blamed for anything that goes wrong (“You just have to relax more”, etc). You discussed the method and the theory. What, exactly, is that method/theory? What do you feel “Internal Power” offer specifically that other forms of martial arts/body organization do not? If its primary benefit is efficient movement, can’t you refine efficient movement through other means? If the goal is to increase martial efficacy, why, frankly, are a lot of the IP guys lousy fighters?

CL: There are a bunch of big issues in that question, but I’ll try to break out a few.

Efficient movement is one of those things that sounds good, but doesn’t really mean that much. Kyuzo Mifune was very efficient, but so was Mike Tyson – and they moved very differently and had different types of bodies. It’s a little like saying “delicious food”, what that means varies. Of course there are many ways to develop efficient movement, and there are many ways to become an efficient fighter. A particular method may be better or worse for a given situation, but no method is really better or worse in and of itself.

IP won’t make you a fighter, any more than strength training will. But most coaches would recommend that you do some kind of strength training because it will help you to be a better fighter – and most people doing strength training are probably pretty poor fighters. They’re different, but often complementary, activities. IP training can help you to organize your body to generate power, sometimes a lot of power, in a very efficient manner that has a lot of longevity. But it does take a while and not everybody will be interested in it. Are there other ways? Sure there are.

IP methods aren’t monolithic, so talking about theory is going to vary – but in addition what I mentioned above I would add that most internal arts are trying to develop whole body power that rely more on movement within the frame of one’s body than the momentum of the weight of that frame moving forward as a whole, and this usually involves some degree of “softness” in order to facilitate the maximum usage of the body frame.

A lot of demonstrations are bad, that’s true. Similar things happen in Aikido – you’re engaged in a cooperative training method to learn a certain skill, and like all rulesets folks learn how to game that ruleset in order to look “good” while forgetting that the ruleset, especially in uke-nage based training methods, is completely artificial. That doesn’t mean that it’s a poor training method, just there are pitfalls.

The “it has to be felt” thing is all about that common frame of reference from above. I’m not sure what you mean by blaming uke in this case – it’s just about feeling it for yourself.

NP: Starting from the top: It’s true that Mifune and Tyson both moved efficiently while moving very differently, but the difference between that and what I see with a lot of IP people is that the fruits of an athlete’s labors are a bit more obvious– the person gets thrown or hit when they don’t want to be. I guess I also don’t understand the semantic differences between how an IP person would move and how Mifune or Tyson would move. As I understand it, even for different ends, efficient movement is efficient movement. A judoka and a violin player are both using gross and fine motor movements– the difference is that a boxer or violin player or yoga instructor can explain, generally in very simple terms, how they are doing what they are doing. IP people have, in my experience, a very complex vernacular that seems to shut off any understanding of the movements until you’ve already invested.

The “It has to be felt” line gets me because, I can look at any athlete, in any discipline (be it ballet or boxing) and while I can’t replicate their movements, I can understand that they are moving efficiently and correctly just by watching them. I don’t necessarily see that in IP demonstrations, where someone wiggles a hip and their partner flies across the room. That’s where you get people comparing IP people to the no-touch people– a fundamental disconnect between what is normally needed to move another person that way (kuzushi, etc) and what they see in the IP demonstration (none of that). What are they missing?

Regarding fighting: I appreciate your saying that IP won’t make you a fighter, but could you pass that along to the rest of the IP community? There seems to be a disconnect– where on the one hand, IP is touted by some as a health/wellness exercise and on the other hand you see people in martial arts uniforms looking incredulously at their IP master as he/she manipulates someone’s balance or throws them or whatever, and these students then swear that their instructor is “too deadly for the ring” or whatever other cliche you want to use.

Is there an intersection at any point between IP and fighting? If so, why isn’t there a better track record for IP people fighting? If not, do you feel the community would be better served by disconnecting from the idea that fighting skill is a goal/sequela of these exercises? Furthermore (and I know I’ve posed a lot of questions here), how would you, as an IP practitioner yourself, convince someone who’s only done internal training that maybe they are NOT as fearsome a fighter as they may believe themselves to be?

CL: A lot of people would call Mifune an IP person, I’m not sure that I would. In any case, yes, it’s hard to see – that’s a large part of why getting direct hands on is usually more reliable. It’s also one factor among many. So two folks hitting may be using different methods of body organization with little visual distinction. But sorting the whole thing out can get complex.

The terms seem to be complex because of that lack of a common frame of reference that I mentioned above, and because folks are trying to describe things that are happening inside the body – I’ve seen some biomechanical descriptions of golf from the internal body structures that are equally opaque to me. Like anything else, once you get some experience with it those things get easier.

Yes, you can describe a lot of what is happening in biomechanical terms (and we do), but part of the difficulty is that knowing the exact biomechanics doesn’t really help that much in execution. For those things, imagery and visualization – intent based approaches work better. That’s the classical method, and actually visualization and imagery is now commonly used among professional athletes. If I ask you to wiggle your ears, which is a purely physical task, describing the exact biomechanics involved is unlikely to actually help you wiggle your ears. But visualization and imagery can often help you access those actions where intellectual description runs into difficulties.

Chris Davis at Martial Body actually has quite a good collection of clear material and explanations, FWIW: https://www.martialbody.com/

For the IP community – there isn’t one, really. There are a lot of folks doing a lot of things, some of them questionable, with no general agreement of who’s even in the community. It’s a lot like the Aikido world.

For fighters, if we’re talking about modern sports fighters, I don’t think that IP has a quick enough return on investment, generally speaking. Mike Tyson went from zero to Olympic gold in three or four years, retooling your body usage just takes too long to compete with that. Even if you invest the time it’s as I said, one factor among many in fighting. Does long distance running make you a better fighter? Probably, but that doesn’t mean that long distance runners are fighters. When you’re talking about IP as a stand alone, it’s just that – a kind of conditioning and body usage. If you’re talking about it as attached to one tactical martial system or another then you have a lot of other factors in play as well.

NP: Tyson never made it to the Olympics but I think I understand what you mean.

I won’t keep you much longer, so in closing: what do you think people outside of IP fundamentally misunderstand about it? What do you think people inside of IP fundamentally misunderstand about it? If you had to make that “elevator pitch” to try and convince IP skeptics that what you’re doing has value beyond a basic conditioning workout, what would you tell them?

CL: As I said earlier, it’s a method of conditioning and usage. That usage can be very useful in martial applications – but that’s best experienced hands on, and that’s basically what I tell folks. Most of all, it’s interesting, much more interesting than your basic conventional physical training, at least to me.

People outside of IP may tend to think that it’s woo woo – but it isn’t, it’s entirely physical and logical (it has to be, really). People inside – well these things are hardly monolithic, but perhaps it’s true that they overestimate how much weight those skills get them in a fight when they may lack other skills or experiences.

NP: Being interesting (and something you’d come back to consistently) is generally what keeps people training more than anything else. Thanks for taking the time to talk to me.

Entrevista con Chris Li sobre el entrenamiento de “poder interno” en artes marciales

18 DE JULIO DE 2019 ~ NICK PORTER

¡Hey gente! Lo que sigue a continuación es una entrevista con Chris Li, un artista marcial que se ha entrenado principalmente en Aikido. Es un gran divulgador dentro de la comunidad de Aikido con respecto a la historia del arte y un tipo muy accesible. También entrena en “poder interno”, que es algo que nunca tuvo sentido para mí, incluso cuando entrenaba Aikido. En el mejor de los casos, parecía una explicación demasiado complicada de la biomecánica. En el peor de los casos, se ve como charlatanería .

Entonces, en lugar de seguir en línea, decidí preguntarle a alguien que lo supiera, y Chris tuvo la gentileza de tomarse un tiempo e intentar explicármelo. Quizás solo soy un mal entrevistador, pero todavía no estoy seguro de haberlo entendido. ¿Qué piensan todos ustedes? ¿Hay algo en el entrenamiento de energía interna? ¿Es útil para artistas marciales?

Chris Li (CL) ha estado entrenando en Aikido desde 1981, y también ha entrenado en Judo con un ex entrenador de los equipos olímpicos japonés y estadounidense y en Karate Shito-ryu, así como varios linajes de Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu. Pasó unos 15 años viviendo, entrenando y enseñando en Japón. Ha estado entrenando con Dan Harden, en su organización Sangenkai, desde 2010.

Nick Porter (NP): Gracias por tomarse el tiempo de hablarme sobre esto. Siempre me ha fascinado la idea del “poder interno”, pero la práctica real frente al discurso me pareció algo difícil de vender. Para comenzar, para que estemos en la misma línea, ¿puedes definir a qué te refieres cuando dices “Energía interna”?

CL: Sam Chin me dijo una vez “lo que pasa con el poder interno es que … es poder. “Y tiene razón, la división entre métodos internos y externos es una forma en gran medida artificial de clasificar métodos generalmente diferentes de uso del cuerpo. Pero todos son poder, todos involucran la mente, el cuerpo y todo lo demás. Por otro lado, tocar el violin y el levantamiento de pesas también son tareas puramente físicas que involucran el mismo cuerpo y la misma musculatura, pero terminan en lugares muy diferentes, por lo que hay cosas que pueden ser muy diferentes y, sin embargo, involucrar los mismos elementos o solo a algunos de ellos. Todos los deportes utilizan tanto la fuerza como la resistencia, pero, por supuesto, a menudo dividimos el acondicionamiento físico en áreas tales como ejercicios de resistencia y desarrollo de la fuerza por pura conveniencia. Entonces, la dicotomía interno/externo es artificial, por supuesto, pero también es conveniente.

Cuando hablo de métodos internos, estoy hablando de métodos que, en general, se refieren a lo que sucede dentro del marco de mi propio cuerpo (en lugar de, por ejemplo, una técnica que se define por lo que sucede en relación con el cuerpo de otra persona). Además, los métodos de los que hablo se basan principalmente en la intención. Por supuesto, todo se basa en la intención, pero el énfasis en la intención en los métodos internos es lo que a menudo está intentando usar o condicionar tu musculatura de una manera que generalmente es diferente de la que normalmente usa.

NP: ¿Sientes que hay una desconexión entre la forma en que se explica el Poder Interno (vs, por ejemplo, la mecánica del tai chi o el yoga) y la forma en que se practica de tal manera que no haya más personas que vean una razón para comenzar a entrenarlo?

CL: Las descripciones son a menudo difíciles porque no tienen mucho sentido sin experimentarlo antes. Entonces sí, eso puede ser un problema. En mi opinión, es algo que hay que sentir. Las personas que se unen a nosotros y terminan quedándose generalmente lo hacen porque estamos haciendo lo que estaban buscando en primer lugar. En otras palabras, habían realizado la investigación por su cuenta y tenían una idea de qué esperar. Pero puede ser que la dificultad de este tipo de entrenamiento excluya, en parte, una breve descripción fácil de entender. Además, no hay un marco de referencia común con la mayoría de la gente como si se estuviera hablando, por ejemplo, de béisbol.

NP: Ayer tuve una gran discusión con algunas personas que trabajan Poder Interno, sobre cómo “tenía que sentirse” y sobre qué es algo que “simplemente no se puede entender”, que son argumentos difíciles de vender en el mundo moderno. ¿Hay alguna forma en que creas que el Poder Interno podría hacerse más comprensible?

Además, mi otra pregunta para ellos (y ahora para usted) es: ¿cómo diferenciar a alguien que sabe lo que está haciendo de una superchería de artista (marcial)? Todo lo que he escuchado es:

Un verdadero maestro de poder Interno es extremadamente raro.

Sin embargo, definitivamente conozco uno.

Entonces, en un sistema que es muy subjetivo (“solo tienes que sentirlo”), ¿cómo puedes saber que lo que sientes es el “poder” real en lugar del poder de sugestión?

CL: Si puedes pensar en una forma de hacerlo más comprensible, ¡estoy abierto a sugerencias! Supongo que realmente necesitamos un “discurso de ascensor”, pero parte de la dificultad es que estas cosas realmente son bastante diferentes. Y eso trae el problema del marco de referencia que mencioné anteriormente.

Como lo dices Bueno, eso también es difícil.

La experiencia con múltiples personas ciertamente ayuda, al igual que la honestidad intelectual. Al final, supongo que debes formarte una opinión y arriesgarte.

Tradicionalmente, supongo que desafiarás a un instructor y verás qué sucede, pero ese tipo de cosas no siempre salen bien …

También debería decir que derrotar o no derrotar a una persona en particular no necesariamente dice mucho sobre el método o la teoría. Todos ganan y pierden cuando ruedas.

NP: Creo que el Poder Interno podría tomar algunas cosas del yoga. A mi modo de ver, el movimiento es movimiento y, en esencia, el movimiento eficiente es simple movimiento. Este video de Kyuzo Mifune ilustra ese punto (nota, se refiere, creo a un vídeo muy conocido de Mizune sensei, uno de los grandes históricos del Judo, demostrando técnicas con alumnos suyos de alto nivel). Entiendo que sus Ike’s le están dando un poco de respeto. Incluso con eso en mente, y con el entendimiento de que no sé nada sobre el Judo, puedo entender y respetar cómo se está moviendo porque cómo se está moviendo parece lógico, simple y eficiente. Comparo eso con muchos de los videos de Poder Interno que veo: donde un uke agarra como si su vida dependiera de ello, se da la vuelta y luego es arrojado a través de la habitación mientras todos miran con asombro. En el mejor de los casos, parece sugestión y un uke muy obediente. En el peor de los casos, comienza a parecerse a las personas KO sin contacto.

Lo que odio del argumento de “tiene que sentirse” es que se cumple por sí mismo y, con demasiada frecuencia, se culpa al uke de cualquier cosa que salga mal (“Solo tienes que relajarte más”, etc.). Hablaste a propósito del método y la teoría. ¿Qué es exactamente ese método / teoría? ¿Qué crees que ofrece el “Poder interno” específicamente que otras formas de artes marciales / organización del cuerpo no ofrecen? Si su principal beneficio es el movimiento eficiente, ¿no puede refinar el movimiento eficiente por otros medios? Si el objetivo es aumentar la eficacia marcial, ¿por qué, francamente, muchos de los tipos de Poder Interno son pésimos luchadores?

CL: Hay un montón de grandes problemas en esa pregunta, pero intentaré aclarar algunos.

El movimiento eficiente es una de esas cosas que suena bien, pero en realidad no significa mucho. Kyuzo Mifune fue muy eficiente, pero también lo fue Mike Tyson, y se movían de manera muy diferente y tenían diferentes tipos de cuerpos. Es un poco como hablar de “comida deliciosa”: lo que eso significa varía. Por supuesto, hay muchas maneras de desarrollar movimientos eficientes, y hay muchas maneras de convertirse en un luchador eficiente. Un método particular puede ser mejor o peor para una situación dada, pero ningún método es realmente mejor o peor en sí mismo.

El Pode Interno no te convertirá en un luchador, como tampoco lo hará el entrenamiento de fuerza. Pero la mayoría de los entrenadores recomendaría que realices algún tipo de entrenamiento de fuerza porque te ayudará a ser un mejor luchador, y la mayoría de las personas que hacen entrenamiento de fuerza son probablemente luchadores bastante pobres. Son actividades diferentes, pero a menudo complementarias. El entrenamiento de PI puede ayudarte a organizar tu cuerpo para generar energía, a veces mucha energía, de una manera muy eficiente que tiene mucha longevidad (¿?). Pero lleva un tiempo y no todos estarán interesados en ello. ¿Hay otras formas? Claro que los hay.

Los métodos de Poder Interno no son monolíticos, por lo que si hablamos de teoría el asunto variará, pero además de lo que mencioné anteriormente, agregaría que la mayoría de las artes internas tratan de desarrollar el poder de todo el cuerpo que es algo que se basa más en el movimiento dentro del marco del cuerpo que el ímpetu del peso de ese marco que avanza en su conjunto, y esto generalmente implica cierto grado de “suavidad” para facilitar el uso máximo del marco del cuerpo.

Demasiadas demostraciones (exhibiciones) son malas, eso es cierto. Suceden cosas similares en el Aikido: participa en un método de entrenamiento cooperativo para aprender una determinada habilidad y, como en todos los conjuntos de reglas, la gente aprende a jugar ese conjunto de reglas para verse “bien” mientras se olvida de que el conjunto de reglas, especialmente los métodos de entrenamiento basados en el trabajo uke-nage, es algo completamente artificial. Eso no significa que sea un método de entrenamiento deficiente, solo que existen dificultades.

Lo de que “tiene que sentirse” tiene que ver con ese marco de referencia común desde arriba. No estoy seguro de lo que quieres decir con culpar a uke en este caso: se trata de sentirlo por ti mismo.

NP: Comenzando desde arriba: es cierto que Mifune y Tyson se movian eficientemente haciéndolo de manera muy diferente, pero la diferencia entre eso y lo que veo con muchas personas con IPI es que los frutos del trabajo de un atleta son un poco más obvios: la persona es arrojada o golpeada cuando no quiere serlo. Supongo que tampoco entiendo las diferencias semánticas entre cómo se movería una persona PI y cómo se moverían Mifune o Tyson. Según tengo entendido, incluso para diferentes fines, el movimiento eficiente es un movimiento eficiente. Un judoka y un violinista utilizan movimientos motores gruesos y finos; la diferencia es que un boxeador, un violinista o un instructor de yoga pueden explicar, en términos muy simples, cómo están haciendo lo que están haciendo. La gente de PI tiene, en mi experiencia, una lengua vernácula muy compleja que parece impedir cualquier comprensión de los movimientos hasta que ya estás familiarizado en ellos.

El argumento de “Tiene que sentirse” me atrapa porque, puedo mirar a cualquier atleta, en cualquier disciplina (ya sea ballet o boxeo) y aunque no puedo repetir sus movimientos, puedo entender que se mueven de manera eficiente y correcta con solo mirarlos. No necesariamente veo eso en las demostraciones de PI, donde alguien mueve la cadera y su compañero vuela por la habitación. Ahí es donde aparecen personas que comparan a las personas que trabajan PI con las personas sin contacto: una desconexión fundamental entre lo que normalmente se necesita para mover a otra persona de esa manera (kuzushi, etc.) y lo que ven en la demostración de PI (nada de eso). ¿Qué se están perdiendo?

Con respecto a las peleas: agradezco que digas que el PI no te convertirá en un luchador, pero ¿podrías transmitirlo al resto de la comunidad de PI? Parece haber una desconexión, donde, por un lado, el PI es promocionada por algunos como un ejercicio de salud / bienestar y, por otro lado, se ve a personas con uniformes de artes marciales mirando con incredulidad a su maestro de PI mientras manipula el equilibrio de alguien o los tira o lo que sea, y estos estudiantes juran que su instructor es “demasiado mortal para el fin (para luchar en un cuadrilátero)” o cualquier otro cliché que desee usar.

¿Hay una intersección en algún punto entre IP y la lucha? Si es así, ¿por qué no hay un mejor historial de las personas que luchan con IP? Si no es así, ¿cree que la comunidad estaría mejor atendida al desconectarse de la idea de que la habilidad de lucha es un objetivo / secuela de estos ejercicios? Además (y sé que he planteado muchas preguntas aquí), ¿cómo podría usted, como profesional del Poder Interno, convencer a alguien que solo ha realizado un entrenamiento interno de que tal vez NO son un luchador tan temible como pueden creerse?

CL: Mucha gente llamaría a Mifune una persona IP, no estoy seguro de que lo fuese. En cualquier caso, sí, es difícil de ver, esa es una gran parte de por qué el tener manos directas (nota : poner las manos directamente si te un profesor de PI) suele ser más confiable. También es un factor entre muchos. Entonces, dos personas que golpean pueden estar usando diferentes métodos de organización del cuerpo con poca distinción visual. Pero resolverlo todo puede volverse complejo.

Los términos parecen ser complejos debido a la falta de un marco de referencia común, como ya mencioné anteriormente, y porque la gente está tratando de describir cosas que están sucediendo dentro del cuerpo. He visto algunas descripciones biomecánicas del golf desde las estructuras internas del cuerpo, que son igualmente opacos para mi. Como con cualquier otra cosa, una vez que tenga algo de experiencia con eso, las cosas se vuelven más fáciles.

Sí, se puede describir mucho de lo que está sucediendo en términos biomecánicos (y lo hacemos), pero parte de la dificultad es que conocer la biomecánica exacta no ayuda mucho en la ejecución. Para esas cosas, las imágenes y la visualización, los enfoques basados en la intención funcionan mejor. Ese es el método clásico, y en realidad la visualización y las imágenes es algo que actualmente se usan comúnmente entre los atletas profesionales. Si le pido que mueva las orejas, que es una tarea puramente física, es poco probable que describir la biomecánica exacta involucrada realmente lo ayude a moverlas. Pero la visualización y las imágenes a menudo pueden ayudar a acceder a aquellas acciones donde la descripción intelectual se encuentra con dificultades.

Chris Davis en Martial Body en realidad tiene una buena colección de material claro y explicaciones.

En relación a la comunidad de PI: en realidad no hay solo una. Hay muchas personas que hacen muchas cosas, algunas de ellas cuestionables, sin un acuerdo general de quién está en la comunidad. Se parece mucho al mundo del Aikido.

En relación con los luchadores, si hablamos de luchadores deportivos modernos, no creo que la propiedad intelectual tenga un retorno de la inversión lo suficientemente rápido, en general. Mike Tyson pasó de cero a oro olímpico en tres o cuatro años, reorganizar el uso de su cuerpo lleva demasiado tiempo para competir con eso. Incluso si inviertes el tiempo es como dije, un factor entre muchos en la lucha. ¿Correr largas distancias te hace un mejor luchador? Probablemente, pero eso no significa que los corredores de larga distancia sean luchadores. Cuando se habla de Poder Interno como algo independiente, es solo eso: un tipo de acondicionamiento y uso del cuerpo. Si estás hablando de eso como un sistema marcial táctico u otro, también tienes muchos otros factores en juego.

NP: Tyson nunca llegó a los Juegos Olímpicos, pero creo que entiendo lo que quieres decir. No le voy a entretener mucho más tiempo, así que para concluir: ¿qué cree que las personas fuera del entorno del PoderInterno fundamentalmente malinterpretan? ¿Qué crees que las personas dentro de PI entienden fundamentalmente al respecto? Si tuviera que hacer ese “discurso de ascensor” para tratar de convencer a los escépticos de IP de que lo que está haciendo tiene un valor más allá de un entrenamiento de acondicionamiento básico, ¿qué les diría?

CL: Como dije antes, es un método de acondicionamiento y práctica. Esa práctica puede ser muy útil en aplicaciones marciales, pero eso es lo mejor con experiencia, y eso es básicamente lo que le digo a la gente. Sobre todo, es interesante, mucho más interesante que tu entrenamiento físico convencional básico, al menos para mí.

Las personas que no pertenecen al PI pueden tender a pensar que todo esto es charlatanería, pero no lo es, es completamente físico y lógico (tiene que serlo realmente). Gente de adentro: bueno, estas cosas no son monolíticas, pero tal vez sea cierto que sobreestiman cuánto peso les dan esas habilidades en una pelea cuando pueden carecer de otras habilidades o experiencias.

NP: Ser interesante (y algo a lo que volverías constantemente) es generalmente lo que hace que la gente entrene más que cualquier otra cosa. Gracias por tomarte el tiempo de hablar conmigo.

Published by: Christopher Li – Honolulu, Hawaii

Morito Suganuma (菅沼守人) Sensei

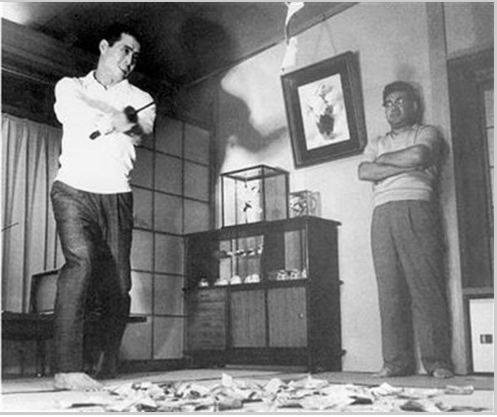

Morito Suganuma (菅沼守人) Sensei Coach Hiroshi Arakawa watches Sadaharu Oh practice cutting – 1964

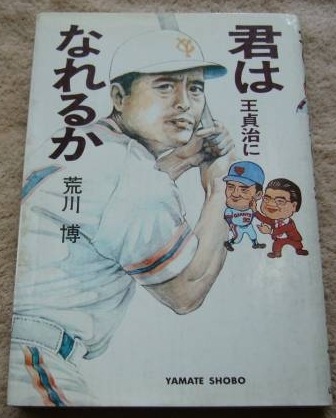

Coach Hiroshi Arakawa watches Sadaharu Oh practice cutting – 1964 “Can you become Sadaharu Oh?” (君は王貞治になれるか)

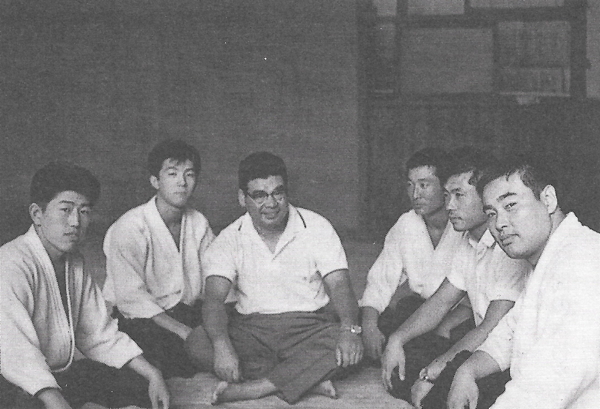

“Can you become Sadaharu Oh?” (君は王貞治になれるか) Morito Suganuma and Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba wait for a train

Morito Suganuma and Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba wait for a train Aikido’s youth power – from right:

Aikido’s youth power – from right:  Calligraphy by Shinryu Umeda

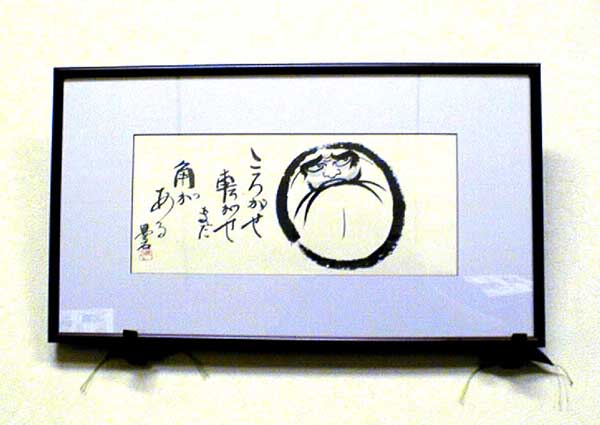

Calligraphy by Shinryu Umeda Daruma and calligraphy by Morito Suganuma

Daruma and calligraphy by Morito Suganuma

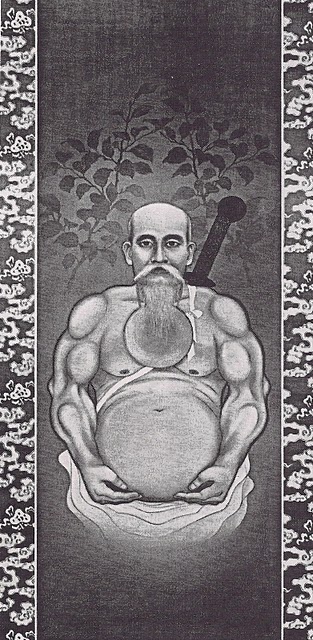

Eiji Tamura’s drawing of Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba

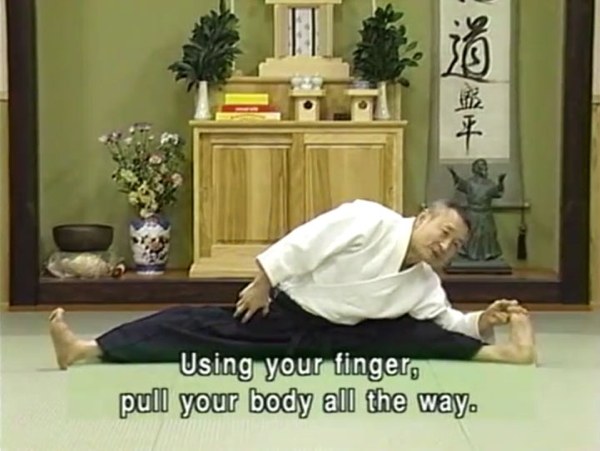

Eiji Tamura’s drawing of Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba Morito Suganuma demonstrating warm-up exercises

Morito Suganuma demonstrating warm-up exercises A Hombu Dojo Bonenkai (Year-end Party). From right to left:

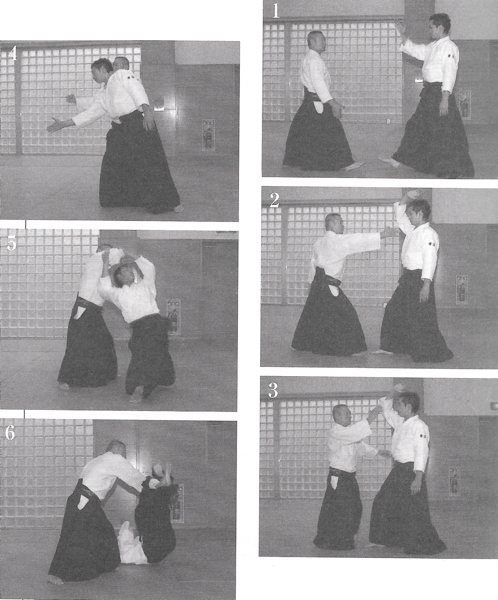

A Hombu Dojo Bonenkai (Year-end Party). From right to left: Suganuma Sensei demonstrates Atemi in Irimi-nage

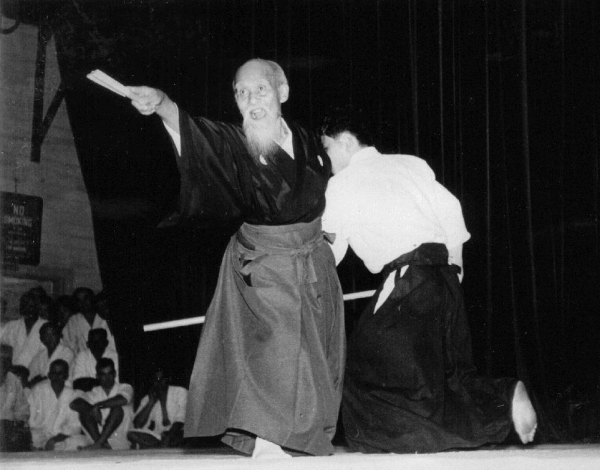

Suganuma Sensei demonstrates Atemi in Irimi-nage Demonstrating with a folding fan

Demonstrating with a folding fan