Ishida was the 5th Chief Justice of Japan,

the second chairman of the All Japan Kendo Federation

and 5th Soke of Yamaoka Tesshu’s Itto Shoden Muto-ryu

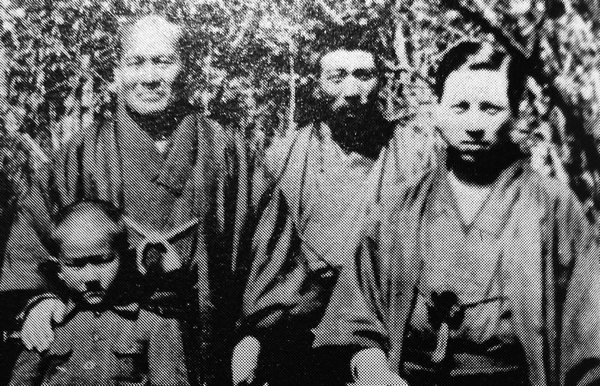

Ishida’s wife (front center) and daughter (back right)

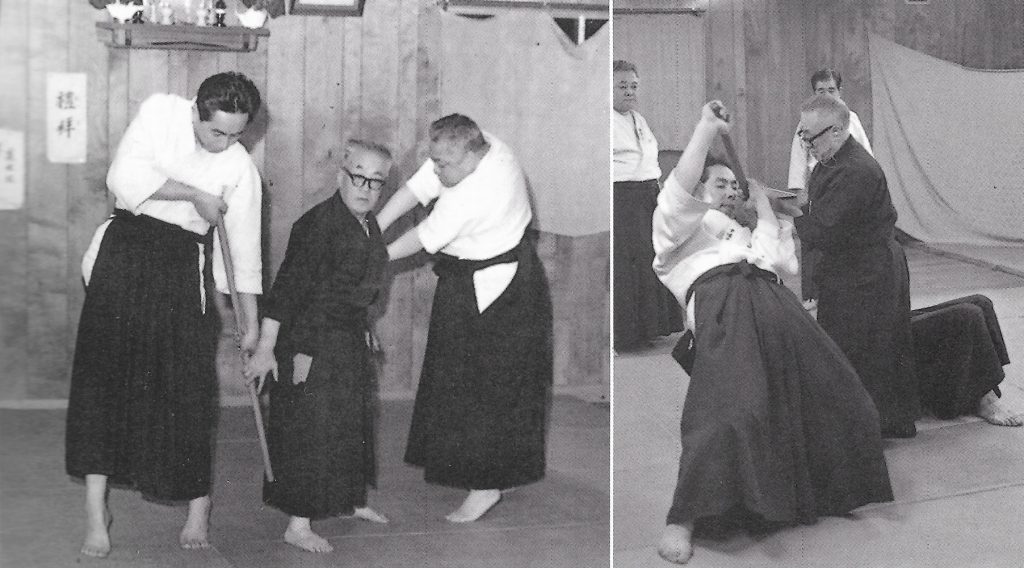

Seigo Okamoto, back left

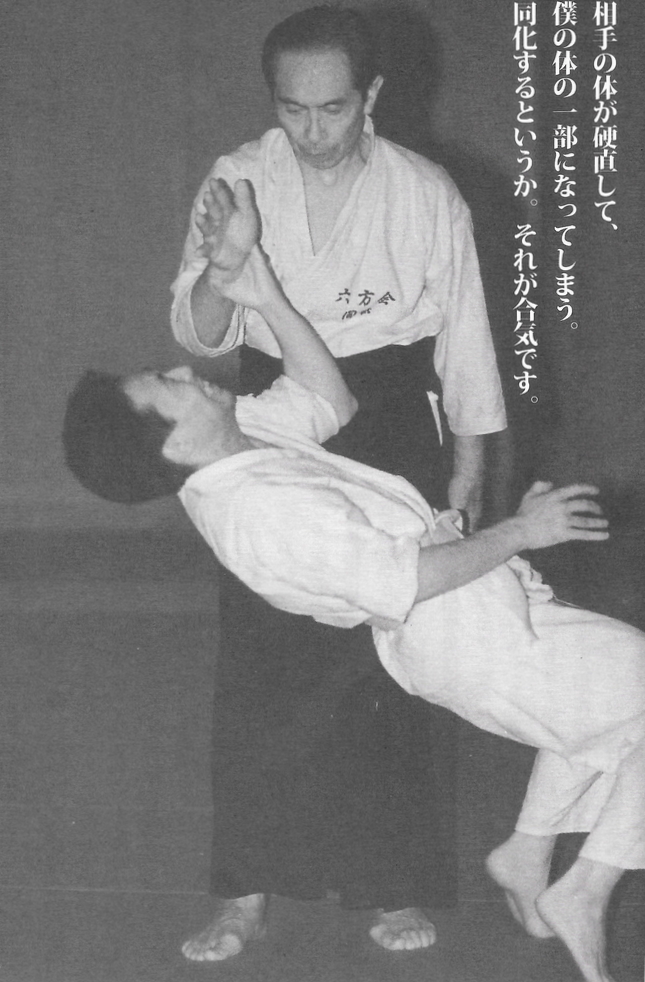

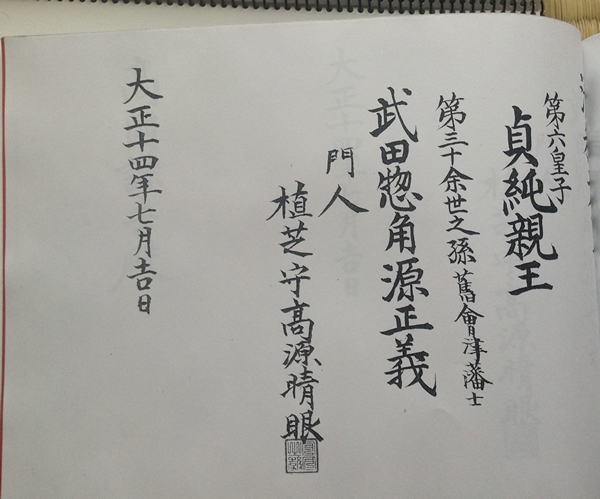

Born in 1894 in Kitami, Hokkaido, Kodo Horikawa began Daito Ryu Jujutsu training with Sokaku Takeda at around the same time as Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba. Sokaku focused on instructing Kodo in “Aiki” because of his size, and Kodo came to be known for techniques that were extremely subtle and soft. In 1930 Kodo received the certificate of “Acting Instructor” or Kyoju Dairi from Takeda (the same certification that Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba received from Takeda in 1922), and was later awarded a certificate of complete transmission in the art, the Menkyo Kaiden. In 1950 he established the Daito Ryu Aikijujutsu Kodo Kai in Hokkaido.

It seems that there are many differences among Daito-ryu techniques.

I have not often viewed the techniques of other schools. I have seen them only at the demonstration held by the Headmaster [Tokimune Takeda]. When I entered Horikawa Sensei’s dojo, there were some people from other schools who criticized his techniques when they saw them saying that he could not really execute a technique with such a small movement and that his students were very meek. However, I believe that there were no such stupid, critical men among the students, seniors and juniors alike of Kodo Sensei. We followed him because his techniques were real. However, there were many who could not continue their practice for long because they found the techniques too difficult.I have learned a lot since I came to Tokyo. In the Roppokai there are some students who have practiced another school’s art for more than 20 years or who are instructors of another art, but they all recognize my art and are gradually making progress mastering techniques which I think is great. I really feel that I must continue to practice all my life.

Interview with Seigo Okamoto Shihan (2) – Aikido Journal Editor Stanley Pranin

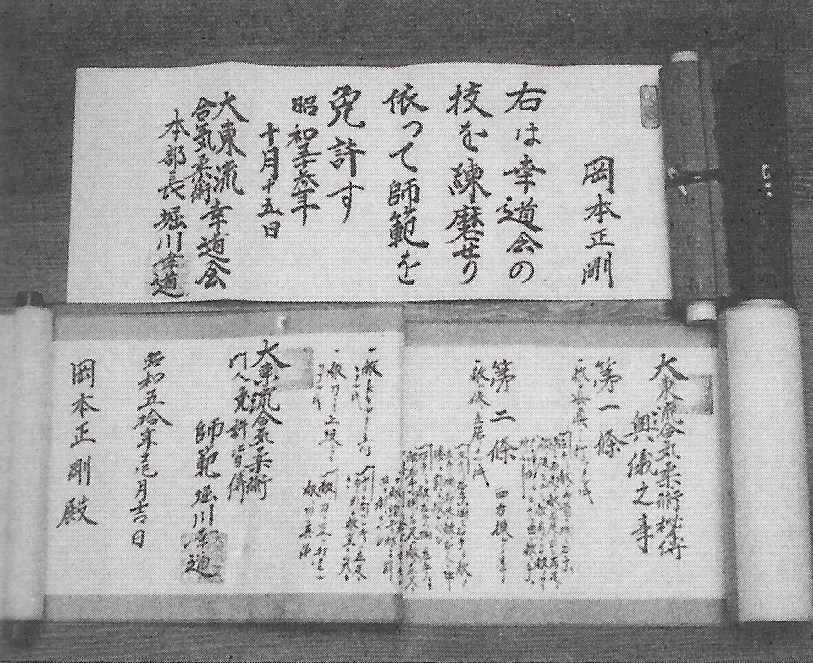

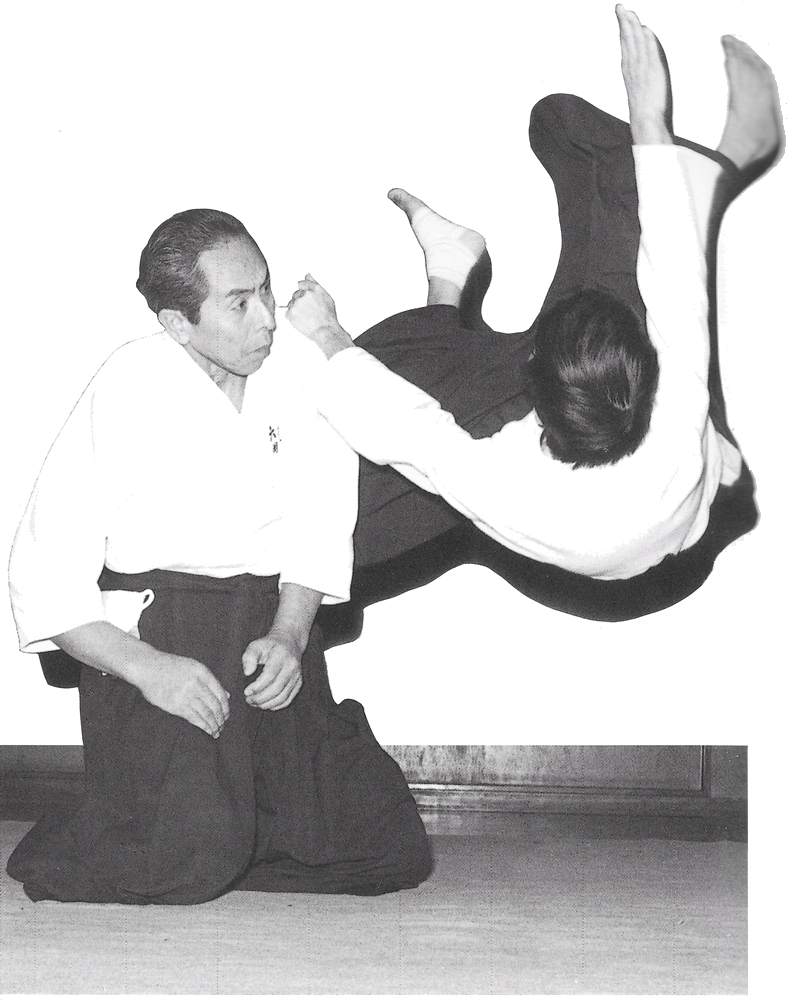

Daito-ryu Aiki Jujutsu Roppokai Founder Seigo Okamoto entered the dojo of Daito-ryu Aiki Jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa at the age of 38. In 1974 he received his 7th dan from Kodo Horikawa, and his Shihan license from Kodo Horikawa four years later in 1978.

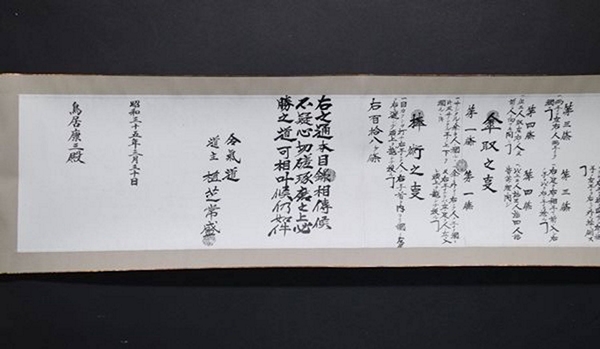

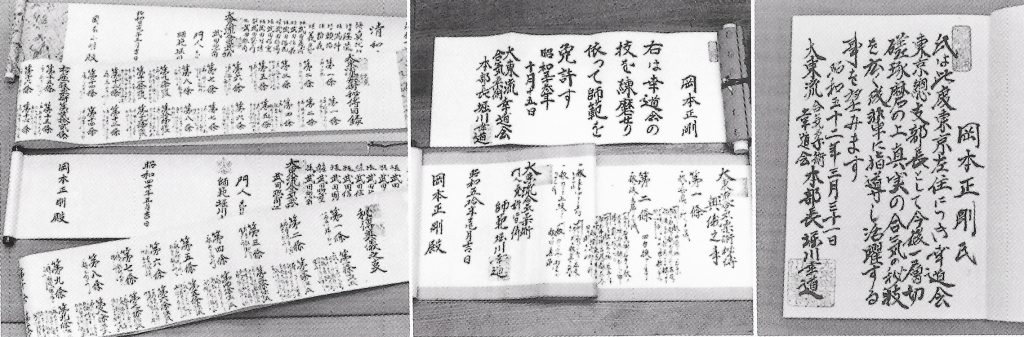

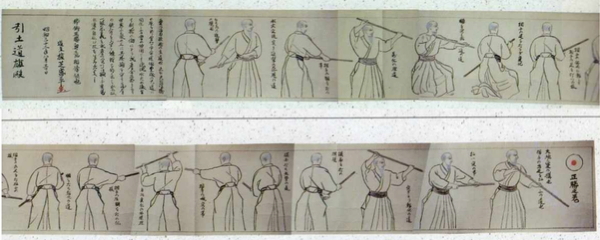

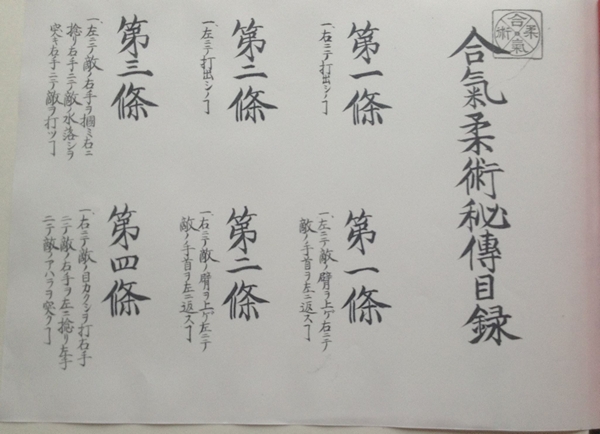

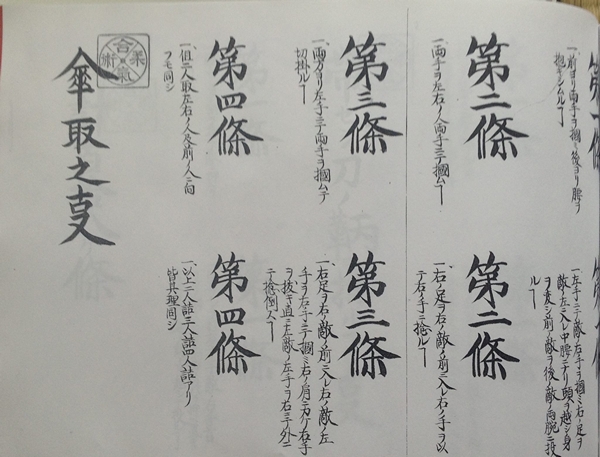

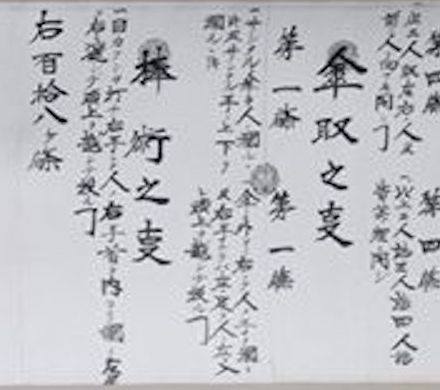

the third scroll in the Daito-ryu Aiki Jujutsu Kodokai

awarded by Daito-ryu Aiki Jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa

Are there are some Aikidoka who try to learn Daito-ryu techniques in order to improve their own Aikido?

Interview with Seigo Okamoto Shihan (2) – Aikido Journal Editor Stanley Pranin

Yes, that’s right. I do not refuse anyone who comes to me. We have an Aikido instructor at our Osaka branch dojo. I think that he is probably utilizing the techniques he learns from us in his Aikido techniques. As I mentioned, I refuse no one who comes to me, but I don’t stop anyone who leaves me either. This is my principle. However, those who come to me must conduct themselves in an appropriate manner. There are some people who come to me with an arrogant attitude as if to say I should be pleased because people like them have come to train while others come with an open attitude toward being taught. People come with many different attitudes. I accept anyone who comes in the latter manner.

This the second part of an English translation of an interview with Seigo Okamoto that appeared in Hiden Koryu Bujutsu vol 4, 1990, published by Gekkan Hiden (月刊秘伝 / “Secret Teachings Monthly”), a well known martial arts magazine in Japan. You may wish to read Part 1 before continuing with this section.

The Essence of Aiki: an Interview with Seigo Okamoto Soshi – Part 2

4 – The Roppokai Technical Method – Difficult to See

Q: Is it difficult to apply technique after one has been grasped strongly?

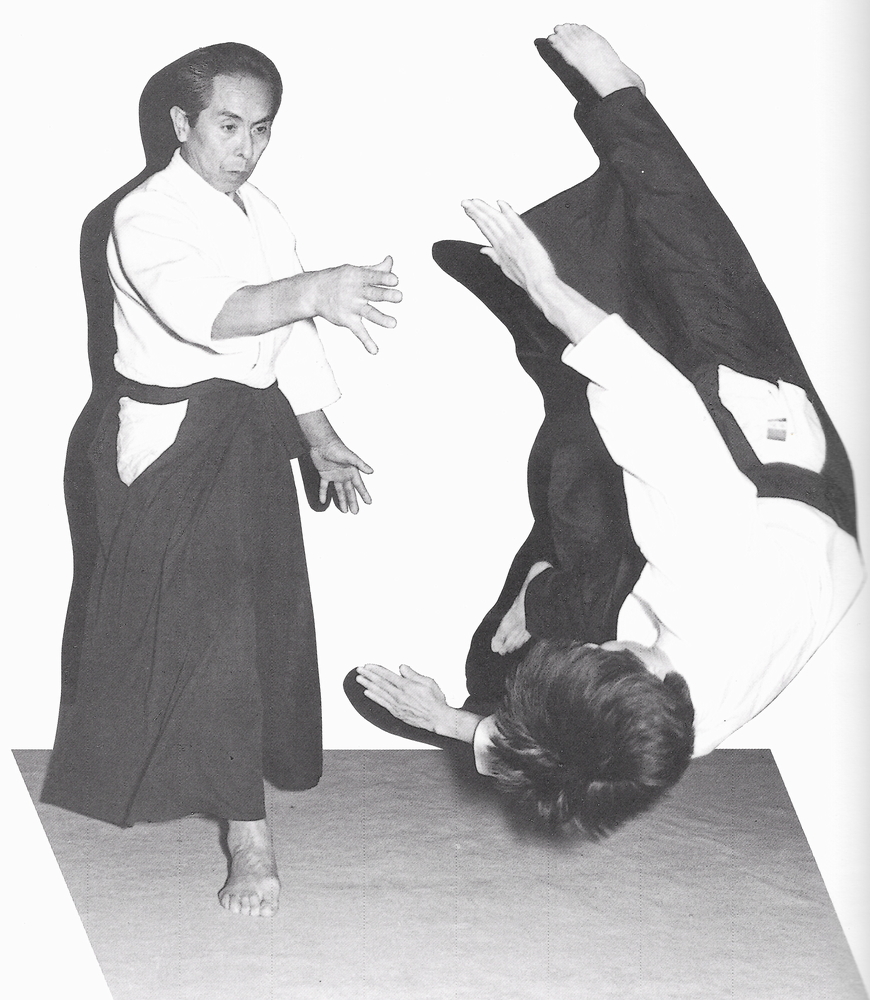

Okamoto: No, if one becomes skilled then it’s possible. But it’s difficult for people in their first three or four years after starting. There are also times when they are grasped strongly by multiple opponents. That’s not strength, it’s technique. With strength they won’t move.

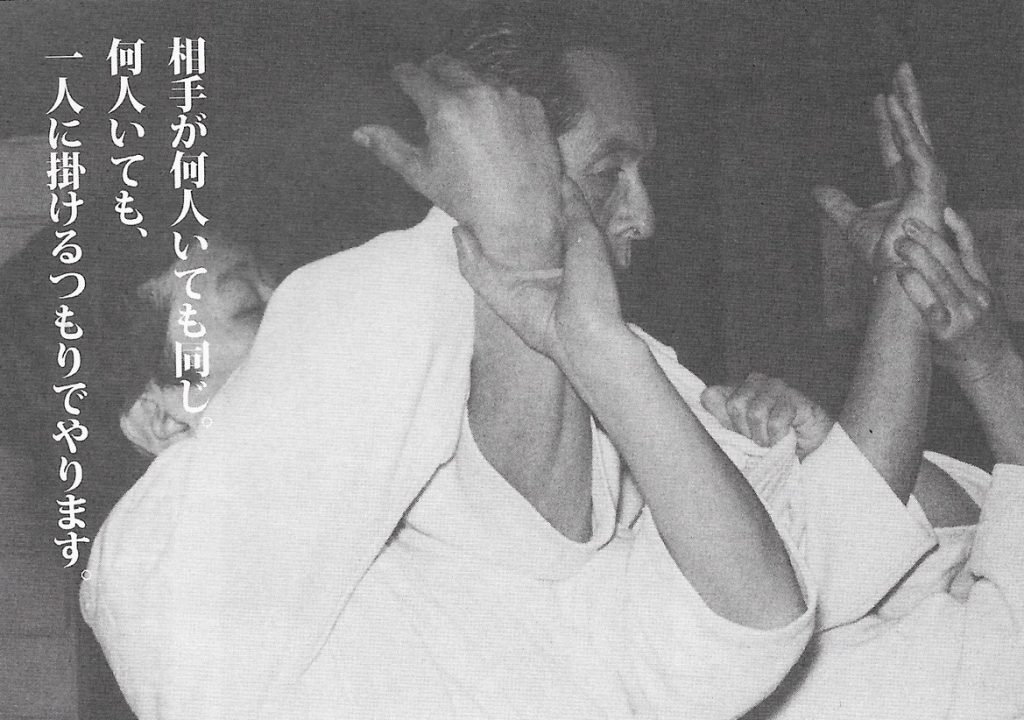

we do it with the intention of applying it to a single person.”

Q: When being grasped by multiple opponents how does it become possible to apply Aiki to the entire group at the same time?

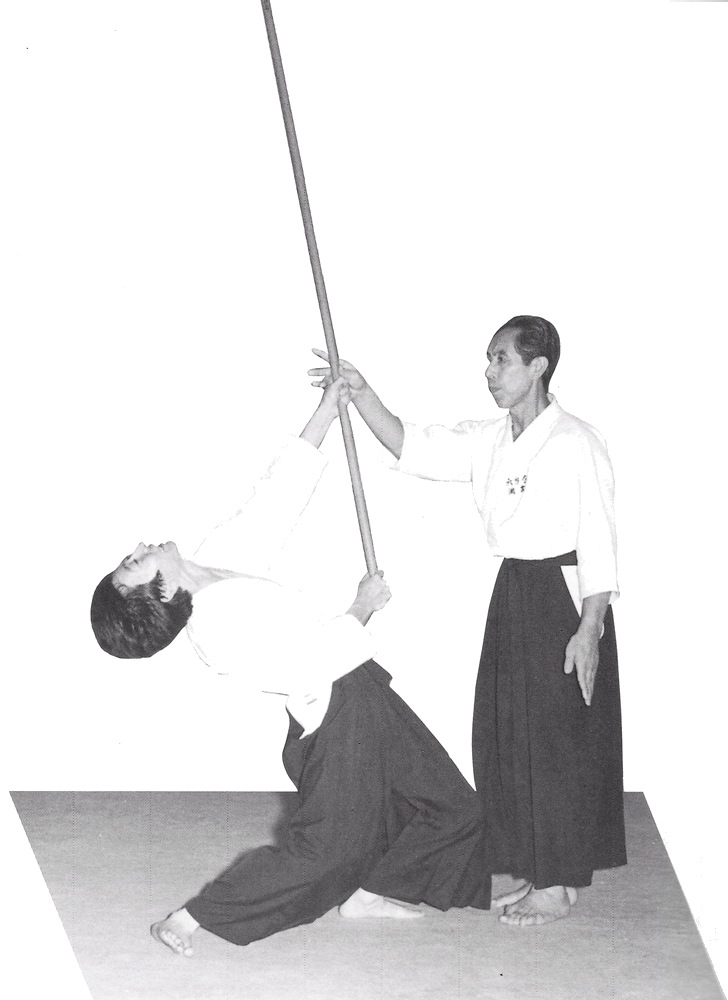

Okamoto: It’s the same. Even if there are five opponents one doesn’t think of them as five people, one does it as if intending to apply it to a single person. If Aiki enters momentarily at the moment at which one is grasped by all of them then they stiffen through their reflex action. When that happens one person is the same as five people – they come along here easily.

For example, five people form a line and the person in front grabs me while each of the people behind pushes on the shoulders of the person in front of them. There is a way to throw these five people. This also is not something for which strength is relied upon. When it is applied to the first person it passes through that person and the same movement is transmitted to the next person and is applied to the next person in the same way and then progressively to each of the people in turn. It’s like toppling dominoes.

Q: So by doing this you can apply it to any number of people?

Okamoto: In order to do that all of them must have their strength turned towards me. For that reason, before one applies it they push or pull a little bit. So I aim for the time at which all of the people have their strength turned towards me and then apply it with a bang! It’s for that same reason that Sokaku would make the opponent angry.

Q: So you build a pile of people in that instant?

Okamoto: Since Aiki has been applied to those that were thrown, while it is still being applied to the person on the bottom I drop the next person on top of them. If there were nothing being done to the person on the bottom then they would just run away before that. However, although they are frozen and in discomfort, it’s not a great amount of pain to be in that position. Once they are released they just laugh it off.

Q: It appears that the Roppokai doesn’t have the same kind of pinning techniques that other branches of Daito-ryu have, is that right?

Okamoto: That’s a common misunderstanding. Taking their arm and holding them down, pushing the opponent down and stepping on them, this is what most people think of as pinning, but here although we don’t hold them down very strongly the opponent is unable to move. Those are the kind of pinning techniques that we have.

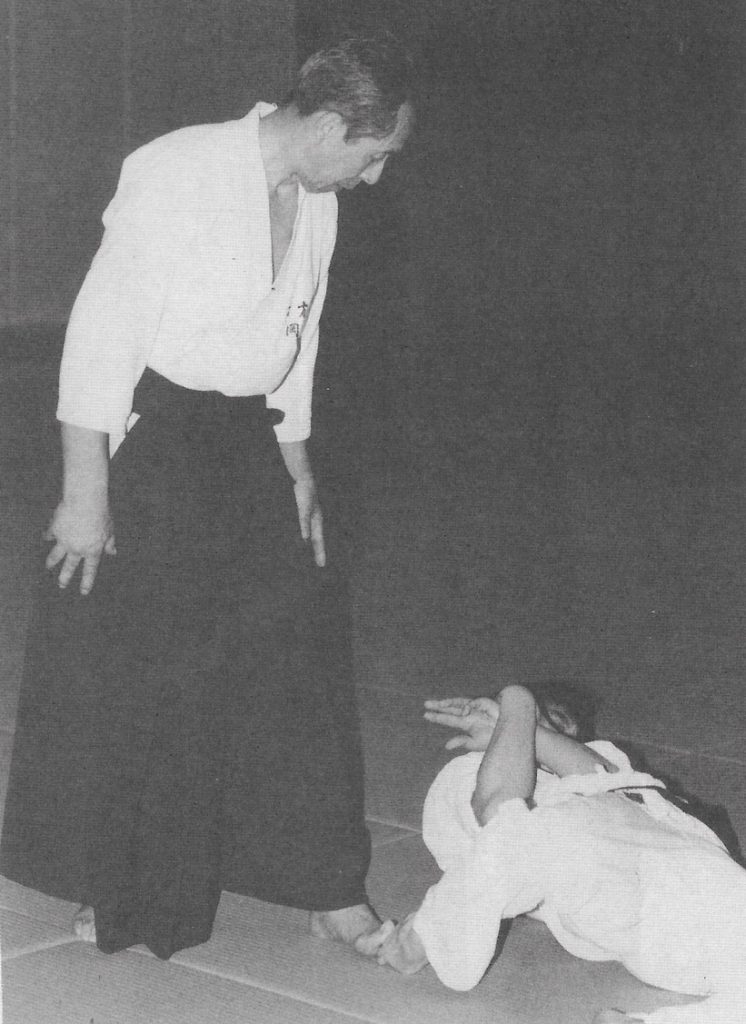

pinning Seigo Okamoto

We throw the opponent when we want to throw them, when we think to pin them then without throwing them we instantly drop them at our feet. Since Aiki has been applied to the opponent, even after they fall they remain stiff. Then if one just presses on them slightly with their foot they will already be unable to move. The technique is so small that you can’t understand it, can you?

Of course, there is jujutsu without Aiki for those people who are just beginning, pinning techniques where one takes the hand of the opponent as they come to strike and hold them down, but we don’t do that very often. That’s because if it’s too much like jujutsu then it becomes different from Aiki.

Q: Also, there are some who are of the opinion that there is no tai-sabaki in the Roppokai?

Okamoto: That’s also incorrect. It would be impossible to throw an opponent by just standing there without doing tai-sabaki. Even when one moves their hand, it’s not that their hand alone is moving. It is because the hand and the body are moving as one that the opponent is thrown. It’s just because the movement is small that it can’t be seen like normal tai-sabaki. Here everything is irimi (“entering”)! In any case, it’s that we move into the bosom of the opponent without stepping back.

Q: It must take quite a bit of training to master these techniques, doesn’t it?

Okamoto: That’s right. It takes a number of years, they can’t be learned that easily. I think that you can understand this by watching the training, but although they can appear the same there is a difference whether the opponent is thrown through the application of Aiki or through the use of strength. Because if the technique is immature it cannot be applied against resistance. For that reason, the truth is that one doesn’t just fall when they are thrown, one helps the other person to develop their technique while they are being thrown.

The more experienced the person is the more skillfully the technique can be applied. That is because they know the kokyu and the timing, and their responses to the techniques are more sensitive. And again, being sensitive to technique itself is a path to skill.

Q: So, as one becomes accustomed to it does it become possible to steal the opponent’s Kokyu and timing and reverse the technique?

Okamoto: Even in Sumo they say “shiju-hatte-ura-omote” (Note: 四十八手の裏表 – “the forty-eight techniques have a back and a front”, meaning that each of them can be countered), in the end techniques have an ura and an omote. During normal training we don’t do the ura. If we teach the ura from the beginning than everybody would just escape and there wouldn’t be any training. For that reason we only teach the omote in the beginning. There many ways to escape a grip, you see, so the number of techniques grows accordingly.

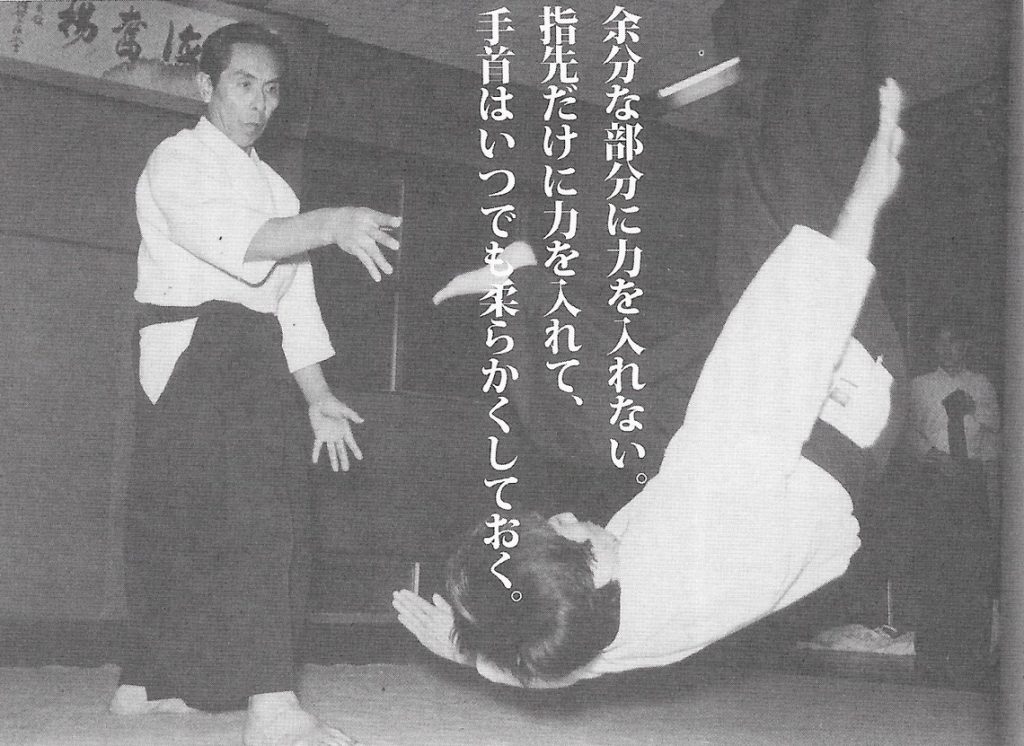

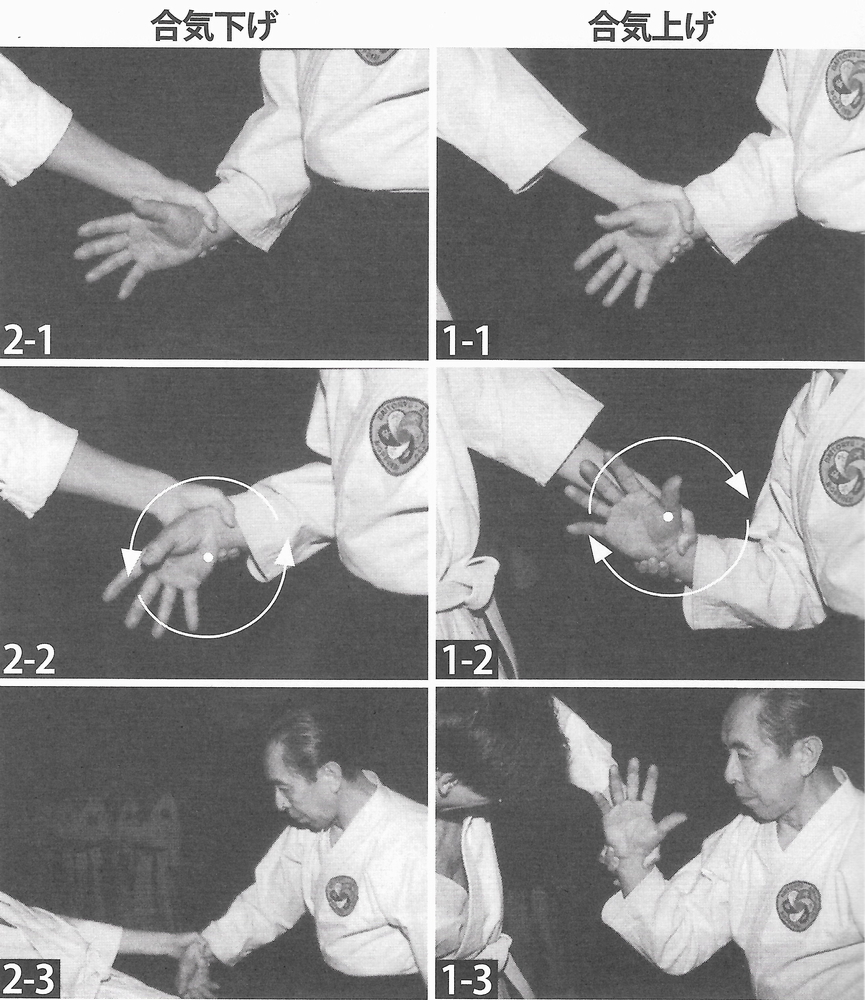

Putting strength only into the fingertips, one always keeps their wrist soft.”

Q: What is the most difficult point in the mastery of Aiki?

Okamoto: To release one’s strength, that is, to eliminate one’s own “tension” (力み) is difficult. Even those like me occasionally have tension! For that reason I always say that it’s okay to have any amount of strength, but it’s no good to be tense. That’s an enormously difficult task. When one feels some kind of momentary strain most people will become tense. Strength enters their shoulders… I think that it’s really a big deal if that can be eliminated. That really comes down to experience. When I say experience, that is to say, shugyo (Note: 修行 / “intensive training”, often with spiritual overtones).

For example, when one spreads their fingers they put strength only in the area around the fingernails, and they always keep their wrist soft. At first I couldn’t understand that, and when Shisho (Note: 師匠 / “Teacher” – Kodo Horikawa) told me to put strength in my fingertips strength would always enter to my wrist even when I tried to put strength only in my fingertips. At some point during my Shugyo I understood that, that is, I became able to do that. Even when I grasp something hard strongly my wrist can move freely. That’s what it is to avoid putting strength where it is unnecessary. It can be said that is one kind of skill.

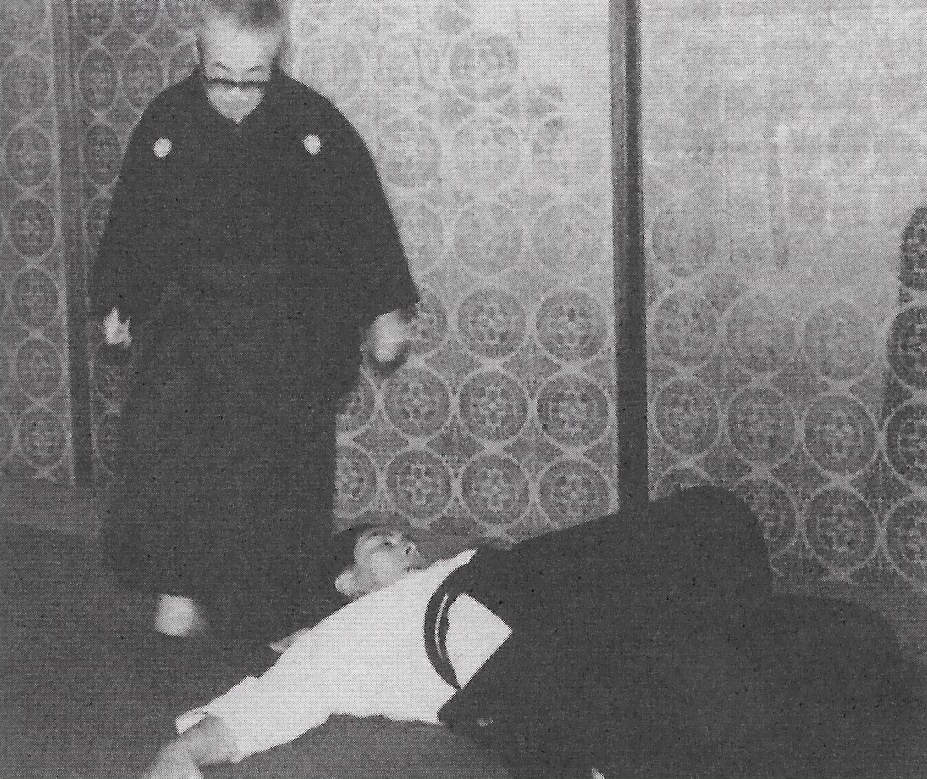

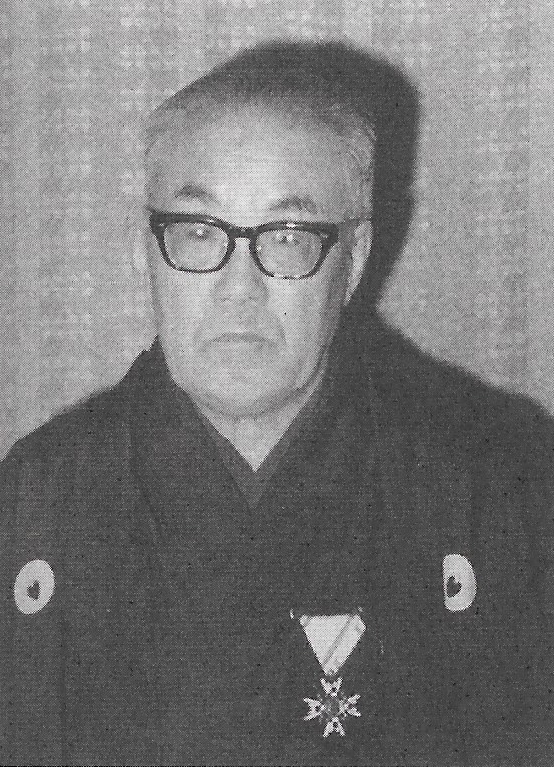

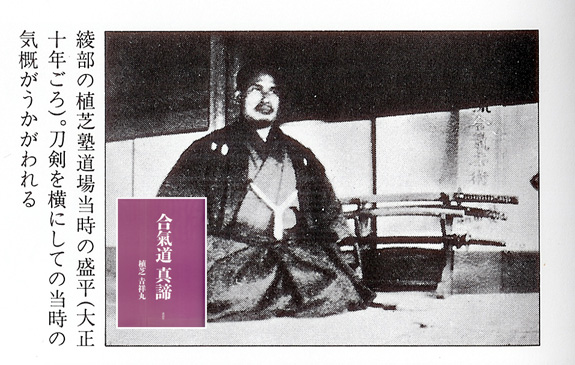

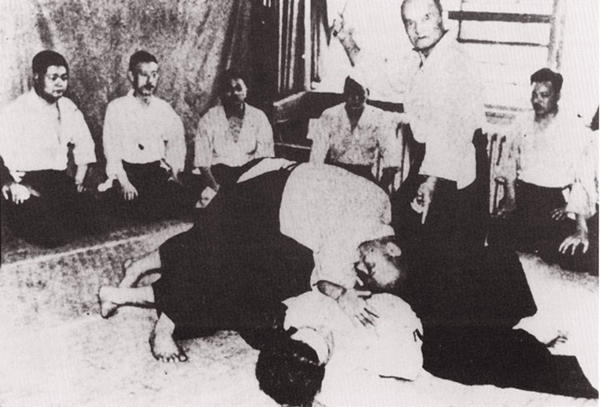

Daito-ryu Aiki Jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa

Q: Do you have a step by step teaching structure?

Okamoto: Daito-ryu techniques are written on the scrolls, and it is said that there are more than 2,880 of them. But that doesn’t mean that I’ve learned all of them. The three scrolls that I received from Shisho in addition to the Shihan Menkyo were Sho-den 118 techniques, Chu-den 30 techniques, and the Oku-den 36 techniques.

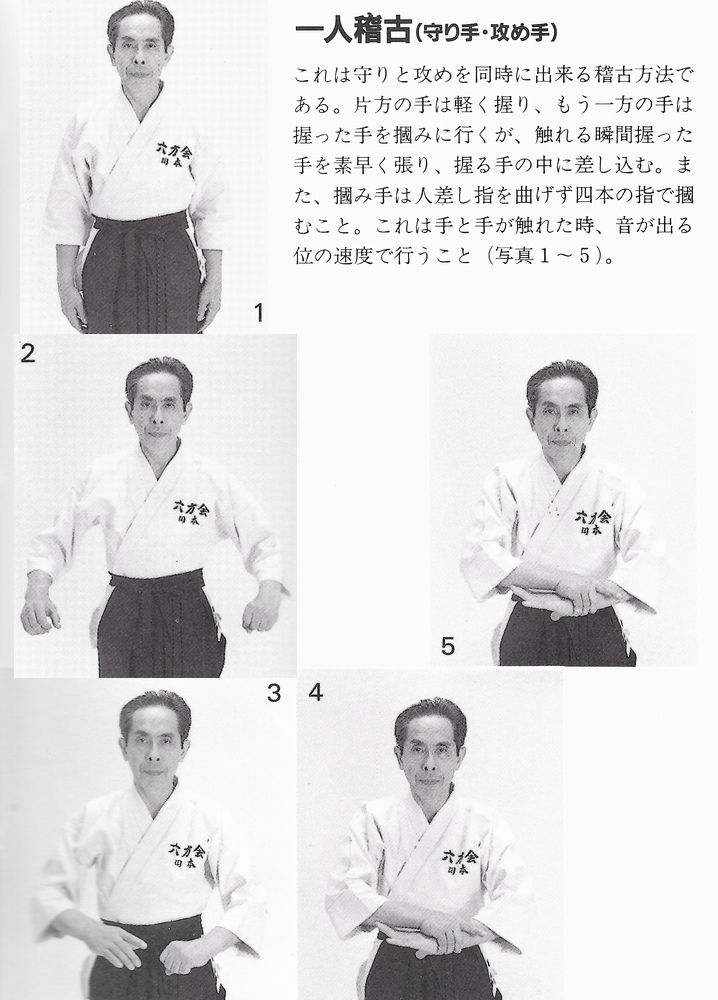

Q: What teaching doctrine do you follow during training at the Roppokai?

Okamoto: In one training session here we teach a mix of techniques from Sho-den to Oku-den. Experienced people and inexperienced people all train together, we don’t divide them. Someone who has just started won’t understand if something is a Sho-den technique or an Oku-den technique, and conversely, I think that it is better not to separate them out when considering them. While not knowing one practices from Sho-den to Oku-den, and that way seems to develop the body more quickly. Just doing the basics is boring, and people tend to tense up.

At the time that I started we would only train in the basics at first. But now people come from many different kinds of Budo. When this happens, even when the technique names or other small details are different and many of them have already mastered basic body movement. Making someone like that do only basics is just pathetic. Someone who has some high rank in another school. For that reason we normally do only one or two of the basics. When we do the basic techniques all together it takes two or three hours.

Q: What are the basic techniques of Daito–ryu?

Okamoto: These are basics that were created by Shisho in Hokkaido. In our case we have changed them a little, but basically speaking they are the same. If one looks at these basic techniques from the viewpoint of other Budo they appear to be high level techniques. That is to say, in the former Aizu Domain Daito-ryu was only taught to warriors of five hundred koku and up (Note: the stipend for a samurai, one koku was supposedly enough rice to feed one man for one year), and the people at that level were already training in other types of bujutsu. So they were a compilation of those things. For that reason, the basic techniques themselves are like hiden (“secret”) techniques, and by just practicing these enough one can become quite strong.

These techniques can be taken as an introduction to Daito-ryu Jujutsu when practiced without Aiki in the beginning, but when one practices them faithfully they all become Aiki techniques. Originally, they had to contain Aiki. Because Jujutsu that does not employ Aiki becomes techniques powered by strength, and when that happens it can become difficult if one is physically inferior the opponent.

Q: What happens when one moves beyond basic techniques?

Okamoto: Applied techniques (応用技). They could be called variations of the techniques that were learned at the beginning. The basic techniques that I was speaking of before, from there they grow and branch. Daito-ryu techniques contain innumerable variations. In total there are two thousand and some hundreds of techniques, but all of those can’t be recorded on three or four scrolls. Further, it’s impossible to practice while consulting the scrolls. The scrolls are something that are given to show that one has learned techniques to a certain degree through actual training, something like a certificate of completion. It’s not that one has completely mastered a technique on the scroll, or that we always practice techniques just as they appear on the scrolls. There is a “feeling” each time – when we go to practice a technique it come to us in a flash.

Further, when we say applied, there are those who assimilate the techniques they have learned well and those who assimilate them poorly. Because of that depending upon the person there are those for whom the techniques can grow and branch later than others. For those reasons, even if one talks about a secret transmission, from the very beginning we are teaching the secrets. Whether one can absorb those as Hiden (“secret transmission”) or they can absorb them as part of the Honden (“main transmission”), whether or not a person will grow will depend upon that.

These days, and this was even so to some degree in the past, all schools practice group instruction. But if you said that because of that everybody progresses at the same pace, that wouldn’t be the case. Out of fifty people perhaps one or two will remain to the end of the transmission. These kind of things happen, don’t they?

There isn’t anybody who teaches carelessly, you know! Everybody wants to transmit their techniques faithfully and repeats themselves until they sweat when they teach. For that reason, all schools teach secrets, but I think that it may be that the difference between Hiden and just ending up as recreation will depend upon how they are taken in by the student.

Q: So how should one train in order to progress?

Okamoto: Practicing humbly and seriously is the best. Going forward humbly as normal without resistance and learn from the feeling at the moment of being touched. In Sumo there is also the moment of the tachiai (Note: 立ち会い – the initial charge at the start of a bout). The opponent springs forward into the engagement. In technique one must also grasp the feeling at the moment that they engage.

Talking about Horikawa Sensei

Q: Next, I’d like to ask if you have any recollections of Kodo Horikawa Sensei?

Okamoto: Horikawa Sensei was an educator, so there aren’t any things like tales of fighting. He was a gentle person, and for his efforts in service towards education in remote areas he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure 5th Class, Gold and Silver Rays (勲五瑞宝章) in Showa year 46 (1971).

Q: How were Horikawa Sensei’s techniques, did they feel sharp?

Okamoto: In Shisho’s case, I don’t know about sharpness. It’s really that a level where one can can feel something such as sharpness is no good. It’s not like when one is thrown with strength, it’s like you touch something and then you’re thrown with a soft feeling. That’s what’s called “Yawara” (Note: 柔 – “ju”, one of the classical terms for jujutsu arts, meaning soft or flexible). It’s a feeling like one is being wrapped in silk wadding and one is carried away. His forearms were really thick! Down to his wrists they were the same thickness, but when we grabbed them they were very soft. They were like a woman’s forearms, they didn’t feel defined. And that’s what it was like when he did things to us. It almost felt as if we were being deceived.

Q: If you were to sort the techniques that you learned from Horikawa Sensei simply, about how many would there be?

Okamoto: About thirty or forty techniques. That’s because if one can can absorb and apply them then they multiply without limit. Well, Aiki itself is only one thing, so one changes that one thing in order to adapt to the requirements of the moment.

Even if one says that there are some 2,880 techniques in Daito-ryu, one can’t really use all of them in reality. Because one must topple them with a single technique. It’s just that if one masters some number of techniques then however one is attacked they will be capable of responding – it must be that this grew to be those some thousands of techniques. It’s not that it’s a good thing the more techniques one has.

It was just before I came to Tokyo, around Showa year 49 (1974), that Soshi told me this – “When one gets to your level, your training up until now gives birth to various techniques. So try and do your best!”. At that time it was already more than ten years after I started.

Scroll entitled “Bojutsu Masakatsu Agatsu” given to Michio Hikitsuchi

by Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba

Q: So does that mean that understanding Aiki itself and becoming able to apply technique strongly takes ten years?

Okamoto: That’s right. That’s not limited to Aiki, doesn’t understanding anything take ten years? But just because I have been doing this for twenty some years, don’t think that I can do things one-hundred percent! I still have to train hard (Shugyo) from now. There are many different kinds of people in the world, and there are always those that are better. It is when one is at the seventh or eighth station (Note: as in climbing Mt. Fuji) that the road above is most difficult, I think. Soshi said this also – “Training is for life. I may seem to be absent minded during the day, but I’m always thinking about techniques!” (Note: 一生修行, “isshou shugyo” “training is for life”).

Published by: Christopher Li – Honolulu, Hawaii

![Ueshiba-ha Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu [Spanish Version]](https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/wp-content/media/morihei-ueshiba-ayabe-1922.jpg)

Certificado Kyoju Dairi Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu expedido a Morihei Ueshiba

Certificado Kyoju Dairi Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu expedido a Morihei Ueshiba Kisshomaru Ueshiba con su padre Ueshiba Juku en Ayabe, 1925

Kisshomaru Ueshiba con su padre Ueshiba Juku en Ayabe, 1925

Aikido Shimbun, número 2 – mayo de 1959

Aikido Shimbun, número 2 – mayo de 1959 “Aikido Nymon”, de Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1975

“Aikido Nymon”, de Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1975 “Aikido Shintei” de Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1986

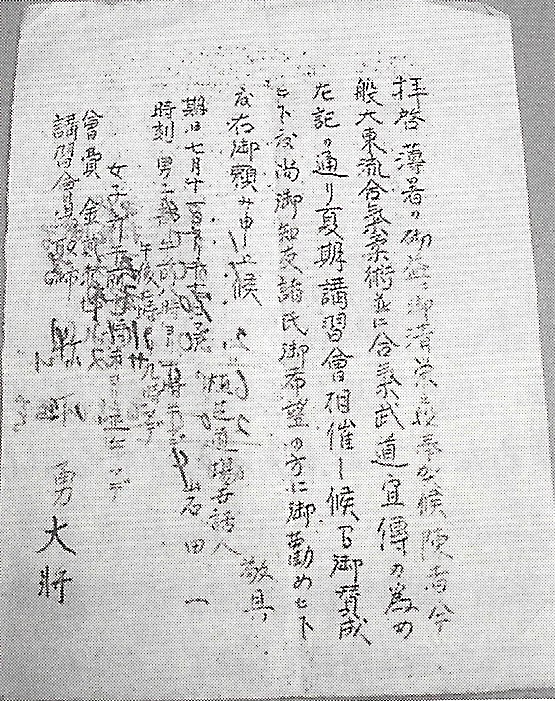

“Aikido Shintei” de Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1986 Invitación para clases de verano con Morihei Ueshiba

Invitación para clases de verano con Morihei Ueshiba Sokaku Takeda en el Asahi Shimbun Dojo en Osaka – 1936

Sokaku Takeda en el Asahi Shimbun Dojo en Osaka – 1936 “Aiki-jujutsu Hiden Mokuroku”, 1925

“Aiki-jujutsu Hiden Mokuroku”, 1925

Hiden Mokuroku expide a Minoru Mochizuki en 1932

Hiden Mokuroku expide a Minoru Mochizuki en 1932 Aikido Hiden Mokuroku

Aikido Hiden Mokuroku Aikido Hiden Mokuroku – detalle

Aikido Hiden Mokuroku – detalle