Muko (Takeo) Nishikido

Muko (Takeo) Nishikido

Muko (Takeo) Nishikido (錦戸無光/武夫) was born in 1940 on Tinian in the Northern Mariana Islands near Saipan. After school in Kumamoto he moved to Osaka, where he began to train in Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu in 1959 and later established a dojo in Tokyo. In 1973 he met Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa in Kitami City in Hokkaido through the introduction of a friend. Upon feeling his Aiki for the first time he decided to discard his previous study of jujutsu and focus on Horikawa Sensei’s approach to Aiki.

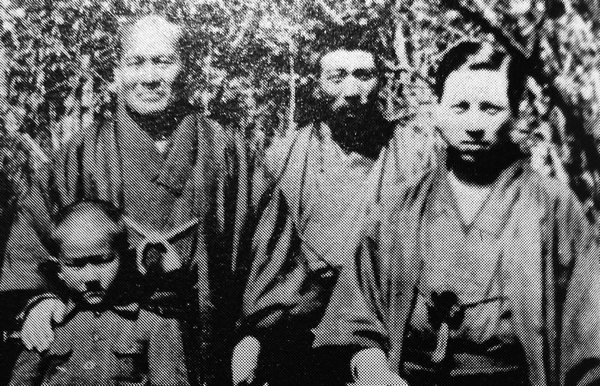

Muko Nishida with Mr. and Mrs. Horikawa in Hokkaido, 1973

Muko Nishida with Mr. and Mrs. Horikawa in Hokkaido, 1973

After commuting to Kitami for two years, he decided to relocate with his family to Hokkaido in order to further his training and received severe individual instruction in addition to the regular training at Horikawa Sensei’s dojo.

He later established his own organization to spread the teachings of Kodo Horikawa called Hikarido (The Way of Light / 光道).

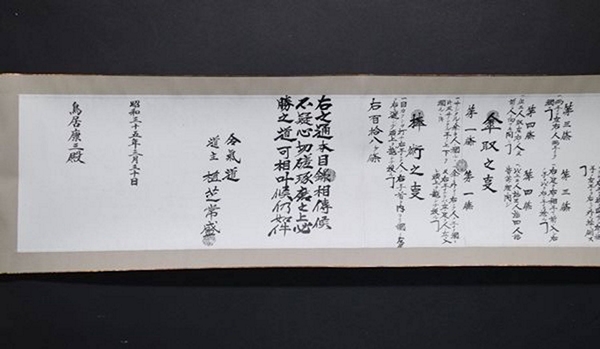

The following article contains excerpts from “The Height of Aiki” (合気の極み), written by Nishikido Sensei and published in Japanese in 2017 by BAB Japan publishing company (BABジャパン出版局), which also publishes the popular martial arts magazine Gekkan Hiden (月刊秘伝 / “Secret Teachings Monthly”).

Some of his emphasis on Ki, love and harmony in Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu may appear to be at odds with common perceptions of Daito-ryu, but it may be helpful to consider his statements in the context of similar statements from other prominent figures in the Daito-ryu world.

- Tokimune Takeda, the son of Morihei Ueshiba’s teacher Sokaku Takeda and the Soke of Daito-ryu Aiki Budo:

“The essential principles of Daito-ryu are Love and Harmony”

“The goal of spreading Daito-ryu is ‘Harmony and Love’, keeping this spirit is what preserves and realizes social justice. This was Sokaku Sensei’s dying wish”

“There is no first attack in Aiki-jujutsu. Endure as much as you should endure. Even when it becomes necessary, neutralize the opponent without causing injury through Aiki.”

- Yukiyoshi Sagawa, one of Sokaku Takeda’s senior students and one-time successor as Soke of the art:

“Aiki Budo is the Way of Human Development”

“Aiki is the fitting together of Ki.

Through this harmonious reconciliation all things under heaven and earth in the universe move peacefully without disturbance. This harmonization is Aiki.”

- Masao Hayashima (早島正雄), who trained with both Sokaku Takeda and Sokaku Takeda’s student Toshimi Matsuda (from the first page of his book – “Taoist Aiki-jutsu – the volume of Internal Power”):

“Aiki-jutsu is said to be the Budo of Harmony.”

- Katsuyuki Kondo, Menkyo Kaiden in Daito-ryu Aiki-budo from Tokimune Takeda and successor to the mainline of Daito-ryu, in an interview with Aikido Journal‘s Stanley Pranin:

What are the main differences between Daito-ryu and aikido?

I don’t think there is any difference. In Daito-ryu, too, practice begins and ends with courtesy (rei). And its final goal is the spirit of love and harmony.

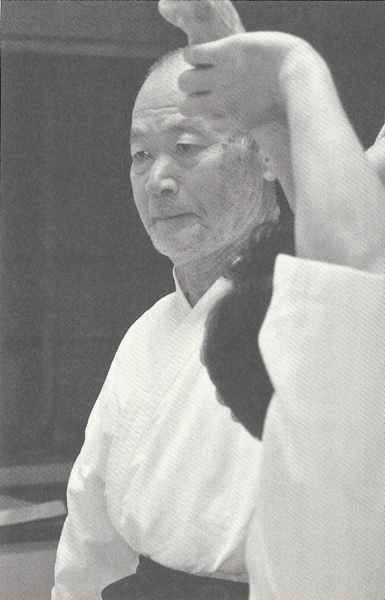

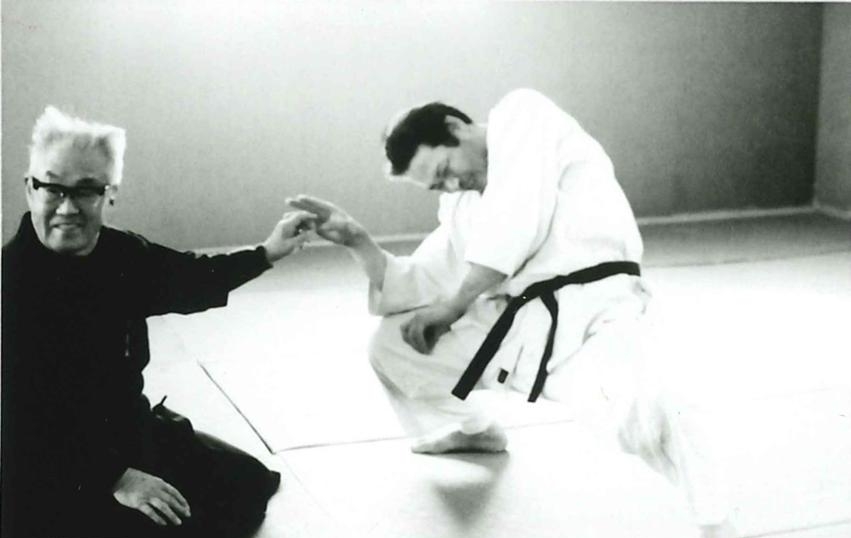

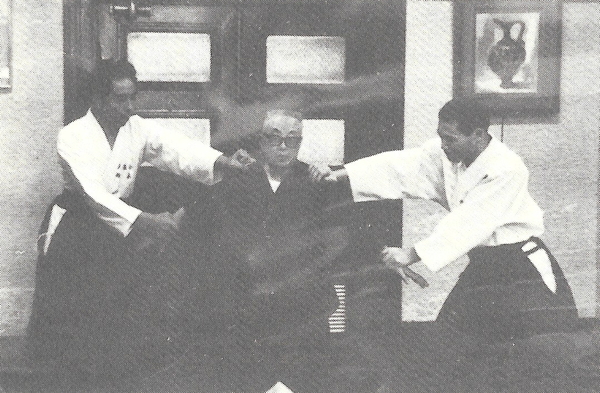

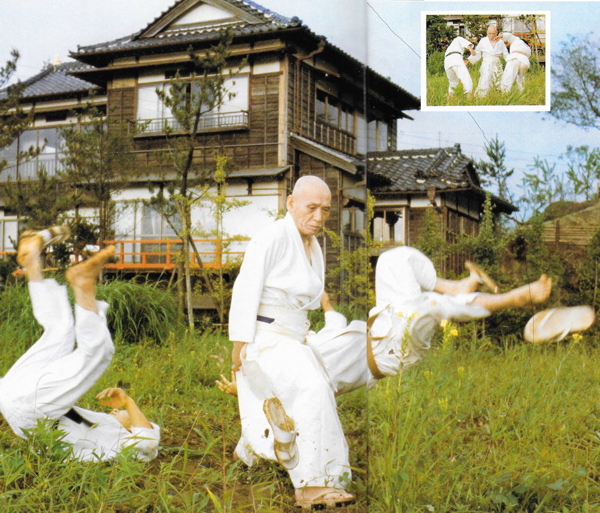

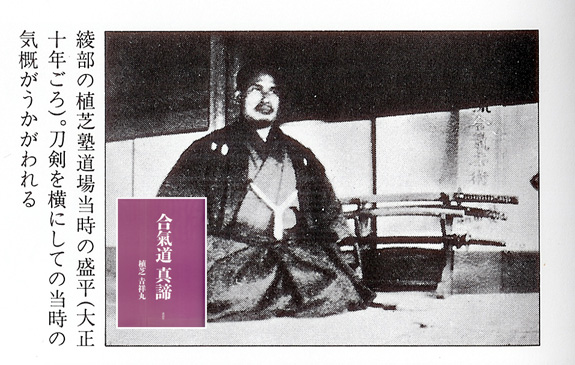

Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa

Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa

applying Aiki to Muko Nishikido

Ai no Bujutsu – Aiki and the Bujutsu of Love

– Muko (Takeo) Nishikido (translation by Christopher Li)

Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu is the bujutsu of “harmony” (和), as was stated by Kodo Horikawa, who established the Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Kodokai, in Showa year 25 (1950) in Kitami City, Hokkaido – “Neither cut nor be cut. Neither strike nor be struck. Neither kick nor be kicked.”. It is a bujutsu that handles the opponent without causing them harm.

In the case of the Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Hikari-do, the level of harmony is gradually enhanced as training progresses from the basic techniques in Shoden to Chuden and Okuden.

Harmony, that is, love.

Why is that? Because it prevents contention. When one uses “Aiki” even the very impulse to counter-attack ceases to arise.

Without harmony one cannot be led to love. The greater the harmony the deeper that love becomes. In Hikari-do we grasp this in our training through the techniques.

At first there is no real feeling when the techniques in Aiki-jujutsu are applied to you. That is because one cannot understand how or what is being done to you.

When Aiki was first applied to me I thought “What is this?”. The will to fight disappears. The desire to attack the opponent disappears.

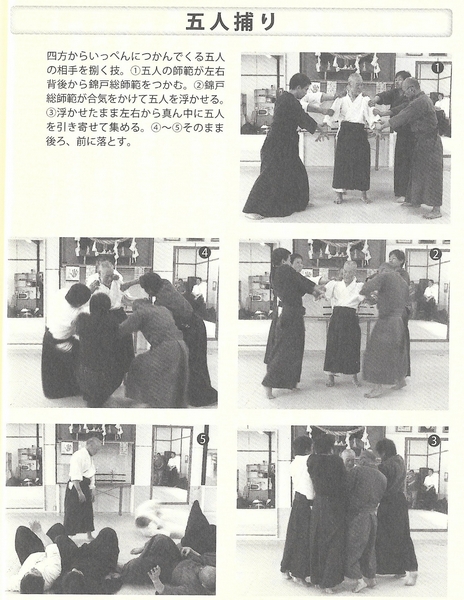

Aiki completely strips away the feeling of the opponent to fight and their strength. That can be stripped away not only for just a single person, but even when there two, three, four, five or six people.

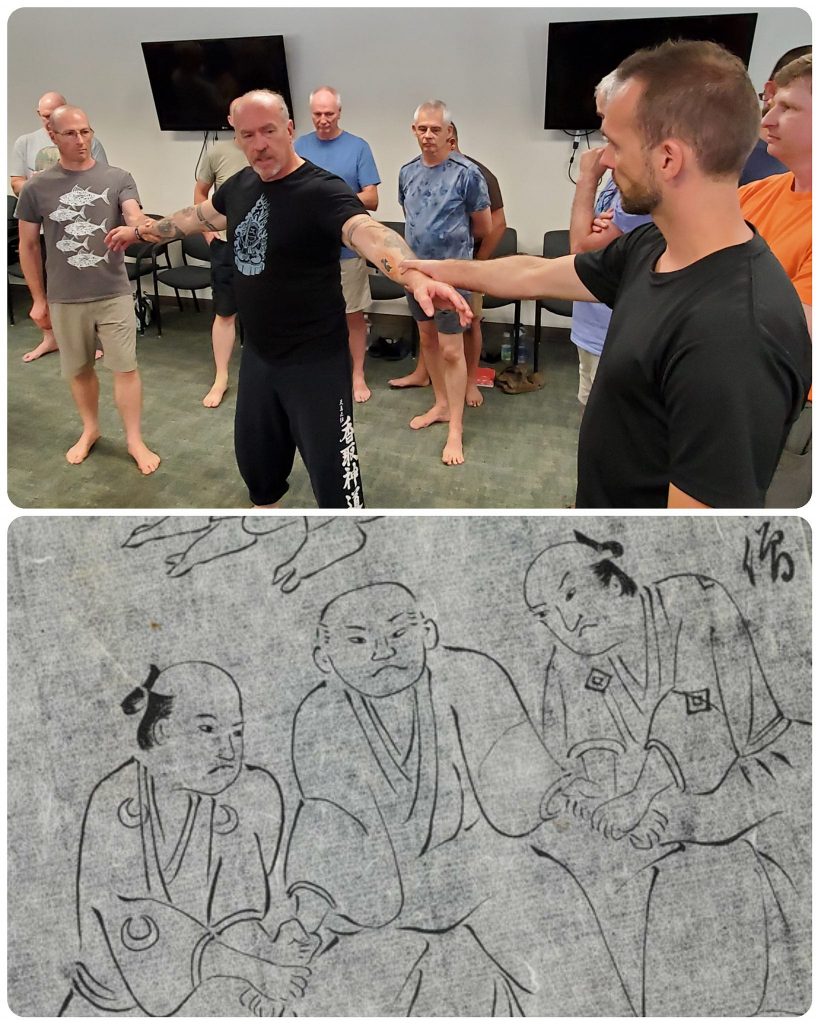

Seated Thousand-armed Kannon Bosatsu

Seated Thousand-armed Kannon Bosatsu

Fujiidera temple, Osaka – 8th century

One works to create a body that that can manage situations like that in an instant. One works to create a body like the Thousand Armed Kannon (千手観音), so to speak.

When one says “thousand”, in the past this meant a number without limit. This means that no matter where one is grabbed on their body they become able to use Aiki.

In a manner of speaking, it means that more harmony can be achieved by two people rather than one, three people rather than two, four people, five people, six people. It is the world of harmony. For that reason, contention disappears.

I think that this is real love. One person, two people, three people, four people, five people, six people – love becomes deeper and deeper.

Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu is the bujutsu of love.

And then, as one draws closer to real training in the inner workings of Aiki, even the smallest portion of the ego becomes unable to enter. One enters into a selfless world without ego.

This is what I have grasped to this point.

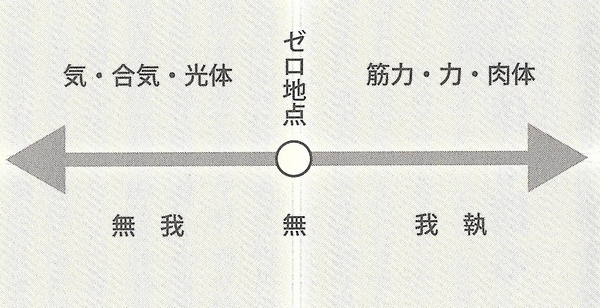

When expressing Aiki as a chart we get something like the diagram above.

On the right side is the world of power, the world physical strength. In terms of the spirit, it is the world of the ego. On the left side is the world of Ki, the world of Aiki. In terms of the spirit, it is the world of egolessness.

In the center is the zero point, in other words nothingness (“Mu” / 無). One who has become enlightened to nothingness comes to this point. “Ah, it’s nothingness” is one kind of enlightenment.

However, even if one becomes enlightened to a state of nothingness, one cannot do anything. Even a master potter will say “Nothing can be done from nothingness”. This is still the zero point. Just coming here one can still go to the right side of the world of strength, the world of the ego, or one can also go to the left side of the world of Ki, the world of Aiki.

The right side of the world of strength, the world of the ego, is comfortable. Strength and ego can be used immediately.

Conversely, the worlds of Ki and Aiki are severe. One cannot grasp the real thing if they compromise. If one thinks to grasp he real thing they must pass through this world of severity.

Even when one attains enlightenment through Zen training, they come to this point of nothingness, the zero point. But if you’re satisfied there then you’ll reach a dead end. There is a much deeper world. Wherever you go, however far you go, there is a world without limits.

The more that one uses Aiki the more that their Ki increases, their harmony increases, their spirit enters into the world without limits.

When those people who have inhabited the world of physical strength, the world of power, the world of the ego until this time train in Aiki-jujutsu they will draw closer to the zero point. That is, nothingness. The world of enlightenment. Return to the origin. From there begins the determination of whether one will either return to the world of physical strength, power, the world of the ego again, or depart for the world of Ki, the world of Aiki.

In Hikari-do there are many types of training done in order to return to the point of nothingness. That can be called the enlightenment of the physical body – once the body has gone that far then next one is able to enter the world of Ki, the world of Aiki.

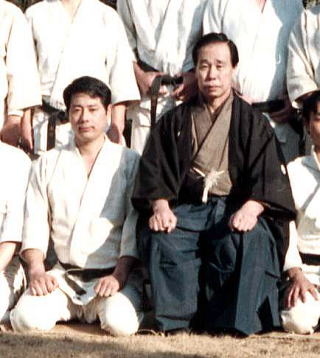

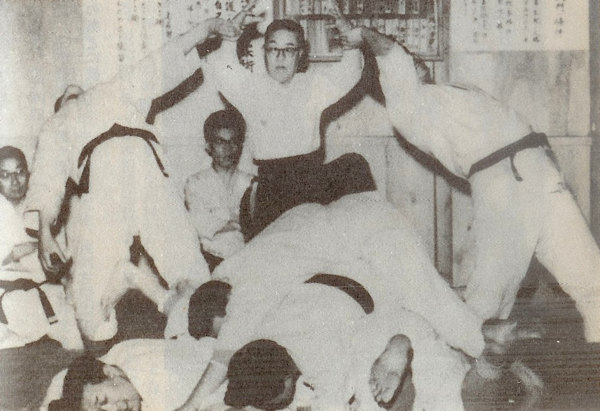

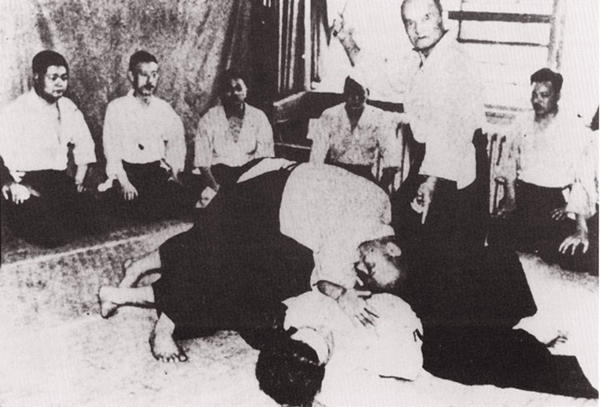

Demonstration at Police Headquarters in November 1973

Demonstration at Police Headquarters in November 1973

Seigo Okamoto – Kodo Horikawa – Muko Nishikido

Building the Ki Body

Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu first builds the “Ki Body” through training in the kihon (“basics”) and then enters into training in Aiki. When building the Ki Body physical strength (power) is not used. When the use of physical strength has ceased completely, there for the first time is the Ki Body.

There was a time during my third year of receiving instruction from Kodo Horikawa Sensei in Kitami, Hokkaido that I realized that my entire body was the Ki Body. “Ah, my entire body is the Ki Body”, I realized. When I truly stopped needing physical strength, that was my first glimpse of Ki.

In other words, I had made my way to the point of nothingness. However, I did not yet understand Aiki. If I had not been able to grasp Aiki it may be that I would have returned to the world of physical strength.

When one trains in Aiki they experience a liberation (moksha) from the physical body. In moksha there is a liberation of the physical body and a liberation of the spirit, Aiki is a liberation of the physical body. One understands – “Ah, this is the Ki Body!”. The body of physical strength becomes the Ki Body.

When compared with Horikawa Sensei’s sixty years of Aiki, my Aiki is still half of that at thirty years. Even if you just look at the shape of his body, Horikawa Sensei is twice as sharp as I am. I am still inexperienced.

That Horikawa Sensei – even past eighty years old he would say “Well, Sokaku Takeda Sensei was much greater. I’m just not there yet…”.

There are those kinds of steps in this world. It is the world of shugyo (“intense training”), so it can’t be helped. One has to build their body. Just one year, or two years of shugyo can’t hope to build the body and leap past sixty years of training.

Hoping to get even a little bit closer to Horikawa Sensei, I thought of my own method of training. I took a heavy wooden sword and swung it five or six thousand times every morning and night. I did that for five or six hours to seven or eight hours every day, and continued for about half a year.

Then, one day when I swung it ten-thousand times, the heavy wooden sword flew up away from me. I thought “Ah, it flew away!”.

So then I started swinging an iron bar several times heavier than the wooden sword. Likewise, I would swing it for a few hours in the morning and the evening about 2,500 times each, 5,000 times a day. And finally the iron bar became weightless and flew up out of my hands.

Normally I wouldn’t be able to swing it with my strength. Even with Ki I couldn’t swing it. I have swung an iron bar with Ki, but I couldn’t swing it more than a hundred times. My hands couldn’t hold it. Instead, I was better able to hold it when swinging with physical strength.

Then I thought “OK, I’ll swing it with Aiki!”. and I swung it with Aiki – two hundred, three hundred, five hundred, six hundred, one thousand, two thousand times I swung. That was the first time that I thought “Ahh, in the end one really has to train…”. If I hadn’t swung using Aiki I would probably have gone back to my original body of physical strength.

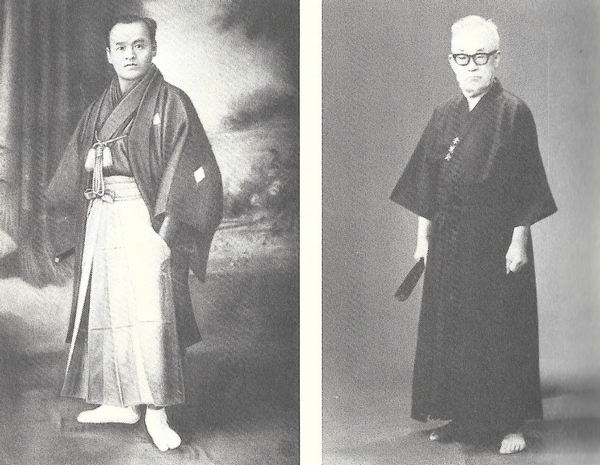

Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa

Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa

Basic Techniques and the Ki Body

Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu does not require even the smallest bit of strength.

That said, it’s not “relaxation” (脱力). I am not saying that relaxation is bad, but when one relaxes the become unable to forge themselves.

In Hikari-do we train from the first steps of basic techniques to training to build a truly physically resilient physique. What I am teaching is training methods for the building of the Ki Body.

I grasped this training method after meeting Horikawa Sensei. If I teach it to someone for one year their body will suddenly change. It will naturally become a physically resilient Ki Body. We have that methodology. In other bujutsu they train by learning techniques, not Ki. For that reason, they are unable to develop the Ki Body.

In order to build the physical body, one would normally lift barbells, or other things, but if you can grasp Aiki then things like that can be done simply. Muscular strength is unnecessary. Conversely, if one uses even a little bit of physical strength then they will be unable to use Aiki.

One must get a firm grasp on the basic techniques. This is important.

If one cannot grasp the basic techniques properly then they will not achieve the Ki Body. They will become unable to attain the real thing. They will develop into a body that is simply composed of techniques.

As long as one grasps the basic techniques they will quickly progress to the next level.

One dayI asked Horikawa Sensei, “Sensei, how many years will it take to get to Aiki?”. When I did that he said, “If you grasp the basics firmly, then two or three years will be enough”.

That’s because if one grasps the basics then they will naturally form the Ki Body. There are not that many people who think to purposely grasp the basics. Those who grasp the basics firmly progress quickly.

But everybody, especially those who have come to learn bujutsu, inevitably tries to throw the opponent or apply a technique and their feelings get drawn in that direction. When that happens those that could see become blind.

Among my students were some who said, “Nishikido can’t use Ki”. But there were also those that, when they finally came to training in the Hiden Ogi techniques, said “Ahh, so there is Ki, there is Aiki!”. Also, there were those who, even when shown “This is Ki. This is Aiki.”, would think “That’s just another technique”.

Training in Ki cannot progress well without a clear spirit of nothingness and concentration. That progress can be made is because that person’s spirit is in a state of clarity.

The state of nothingness is not “indifference” (無関心), it is to be able to see clearly that which is not visible. The “Ki” which was invisible to that point becomes visible. One comes to see it with their spirit. They come to see it clearly.

When one become capable of that one becomes capable of seeing Ki all of the time. To grasp this one time is simple, if one cannot grasp it then of course it is difficult. Those with idle thoughts have a difficult time grasping this.

Even if I teach “If you do this than you will see!”, there are those who are impatient and think “It’s not this, it’s not that”.

The basic techniques are the same, if you do that then you will not be able to see it. It’s quick if you focus on what I am teaching, but people can’t seem to focus.

The Resilient Aiki Body

It is written “Aiki”, but it is read “Ki wo gassuru”. That is what Kodo Horikawa Sensei said. (*See the more detailed explanation towards the end of this article).

In order to use Aiki, the body must become the Ki Body. The entire body becomes the Ki Body, and is used through the unification of Ki.

To become the Ki Body means not to use physical strength. When one does correct basic training in Aiki they will naturally become the Ki Body.

If one does not use physical strength then their strength will degenerate. When physical strength degenerates the muscles also become weaker. It’s difficult to maintain physical strength. In order to triple one’s physical strength they must really participate in a large amount of physical training. But in order to develop the Ki Body it’s acceptable to throw away that physical strength. Normally, in order to achieve the Ki Body, a normal person would take twenty to thirty years at the earliest. When one uses this with unified Ki, the Ki fills the body. As one further unifies and uses this Ki they become more and more filled with Ki. That is even further unified and utilized.

This is Aiki training. This is Aiki conditioning. For that reason, there is no end to Aiki conditioning. And thus, it builds a resilient Ki Body.

When one becomes able to use Aiki the Ki Body becomes even further developed. Even when training in the basic techniques of Aiki the Ki Body becomes further developed.

There is no other bujutsu like this. From basic techniques to a training method that build the Aiki Ki Body.

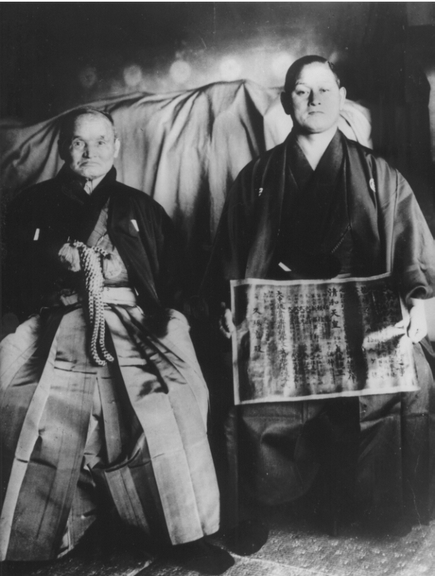

The Aiki bodies of Sokaku Takeda and Kodo Horikawa

The Aiki bodies of Sokaku Takeda and Kodo Horikawa

Once one becomes capable of using Aiki, then one becomes able to build the Aiki Body with Aiki. Not the Ki Body, creating the Aiki Body.

Horikawa Sensei’s techniques were incredible, but his body was also incredible. His body was filled full with Ki. Not a soft, fluffy Ki. He was filled full with a sharp, intense Ki.

Since Sensei was a school teacher, he had never done any kind of physical labor. I always wondered “How did he develop such an incredible body?”. He didn’t have the shape of a Ki Body, his body was in the form of an Aiki Body.

Sokaku Takeda and Takuma Hisa

Receiving Menkyo Kaiden in Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu, 1939

Sokaku Takeda’s body was also firm and sharp. There are pictures of them together, but when compared to Sokaku Takeda’s body Takuma Hisa still looks something like a child.

I think that Takeda Sensei must have handled Takuma Hisa Sensei like a child. Horikawa Sensei’s body was incredible, but Takeda Sensei’s was far and above even that.

Development of the Tendons and Ligaments

All schools of bujutsu build a resilient body through severe training. It is through that that one can become capable of using techniques such that are called “divine techniques”.

Aiki as well was born at the end of the struggles of our ancestors devoting their entire body and souls to their training.

There are several hundred schools of bujutsu in Japan, but the name “Aiki-jujutsu” exists only in Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu.

No matter how weak one’s body is, if they truly understand Aiki and train correctly then they will develop a resilient Aiki Body.

In Daito-ryu one first develops the Ki Body through training in basic techniques, and then begins to use Aiki. When using Ki the tendons and ligaments of the body don’t work very much. However, when one begins to use Aiki after developing the Ki Body the tendons and ligaments begin to work.

There was a time when Horikawa Sensei was admitted to the hospital after he cut his Achilles tendon two-thirds of the way through. At that time one of the doctors in the hospital said in wonder “This person’s Achilles tendon is three times as thick as a normal person’s!”.

Horikawa Sensei’s toes and fingers were also incredible.

Even normally when nothing was happening they were all stretched out wide. Just the same as I when I am stretch my finger and toes out wide to their tips.

The tendons in Horikawa Sensei’s Achilles tendon and his toes and fingers were the result of sixty years of Aiki conditioning. In other words, the tendons and ligaments throughout Horikawa Sensei’s entire body were strongly developed.

When the tendons and ligaments throughout one’s entire body are worked through Aiki training (conditioning) the tendons and ligaments start to develop and one can build the resilient Aiki Body.

Muscles, when one takes even a short break from muscular training, soon become weak. When one becomes of an advanced age their deterioration becomes visible. However, once tendons and ligaments are developed they do not deteriorate. Even when one reaches an advanced age that resilient body is preserved, and one can remain with a youthful appearance indefinitely.

Horikawa Sensei told me “Even if you’re sick in bed for a week or ten days, it’s no hindrance to using Aiki”. Even if you’re sick in bed for a week or ten days, the conditioned body does not deteriorate.

Gassuru Aiki

This happened one day in the third year of receiving instruction from Horikawa Sensei, the first year of receiving individual instruction in Kitami.

I asked Horikawa Sensei loudly “Sensei, Is Aiki kokyu-ho (a breathing method)?”. Horikawa Sensei was very hard of hearing.

Sensei said “What? Kokyu-ho? Hahaha…” – he just laughed and that was the end of it.

Then, after a few days had passed I was having tea at Sensei’s house after morning practice and an Aikido demonstration was being broadcast.

After the demonstration was over Sensei said this – “They call it Aikido, but they aren’t using the slightest bit of Aiki!”. As one would expect, at that time I asked “Sensei, what is Aiki?”.

When I did that Sensei stopped for a moment, took a deep breath, and said “Aiki is…”. I held my breath and watched Sensei’s face. And then this is what he said next.

Sensei told me “Aiki is written Aiki, but the meaning is Ki wo gassuru, it is read Ki wo gassuru.”.

“Sensei! Aiki is Ki wo gassuru?”, I said without thinking. Sensei said, nodding, “Yes, that’s right.”. I said “Thank you!” from the bottom of my heart.

Until that time I had read a number of books about Aikido, but most of them wrote about Aiki as something like “Ki wo awaseru”.

Translator’s Note: Horikawa Sensei appears to be distinguishing between “awaseru” (合わせる) and “gassuru” (合する). “Awaseru” is commonly used in modern Aikido in the meaning of “matching” or “harmonizing” with the opponent. “Gassuru” in this context is used in the sense of “unification” within the body, without relation to the opponent.

Morihei Ueshiba also used this reading of the kanji for “Ai”, both in his 1933 technical manual Aikijujutsu Densho and his 1954 technical manual Aikido Maki-no-Ichi, but slightly more explicitly, as when he used the term “Inyo-gacchi” (陰陽合致) – “the unification of Yin and Yang”.

He later (1963, from a speech at a demonstration at the Hibiya Kokkaido) stressed that this process occurs within one’s own body when he stated that “In Aikido Izanagi no Mikoto Izanami no Mikoto enter and move through this old man’s body” (「合気道は、イザナギの尊 イザナミの尊が爺の体内に入り行っているのだ」) – Izanagi and Izanami standing in for Yin and Yang.

He also presented this in his use of the phrase “Ten-chi-jin Aiki”, the classical Chinese model that “unifies the forces” (“Aiki”) of “heaven and earth” (“Yin and Yang”) in man (‘jin”).

“Aikido is the way and the principle of harmonizing Heaven, Earth and Man

(Morihei Ueshiba – from “Takemusu Aiki”, edited by Hideo Takahashi).

This also lends some elucidation to one of the core principles of Daito-ryu – Aiki-inyo-ho, the “Aiki Yin-Yang Method”, or in this light, a “method for unifying the forces of Yin and Yang”, the classical Chinese union of opposites also cited by Morihei Ueshiba above.

One last point – Nishikido Sensei titled his book 合気の極み, “The Height of Aiki”. But the character used for “height”, 極み, is also the character used for “polarity” in Taiji – 太極 – “supreme polarity”, the union of the opposing forces of Yin and Yang. In the classical Chinese model, Wuji – “nothingness” (無極) becomes Taiji (太極), the manifestation of Yin and Yang. This process was also described by Morihei Ueshiba in terms of the Kototama.

For that reason, when I heard Horikawa Sensei’s explanation I thought “As i suspected, it’s different.”. When I understood that it was “Ki wo gassuru” it became clear to me.

At that time I had already understood the basics of Aiki. I had already realized the concept of the Ki Body. For that reason, I was able to understand “Ah, so that’s what it is!”.

If I hadn’t heard those words from Horikawa Sensei, It may be that I would not have been able to grasp Aiki. I was extremely thankful for that single sentence. Even now I can’t forget the joy that I felt at that time. “Sensei, arigatou gozaimasu!” – I thanked Sensei from the bottom of my heart.

And so, that was how I was able to grasp the principle of Aiki.

There was also another event. One day I was watching Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba’s demonstration at Horikawa Sensei’s home. I watched, thinking “Ah, incredible!”.

I was able to see clearly how Ueshiba Sensei was moving. “Ah, I can see how Ueshiba Sensei is moving!”, I felt.

Previously, I had not felt that way. I just thought “Ueshiba is incredible. Aikido is incredible.”.

But I was able to see it. I saw clearly what Ueshiba Sensei was doing and how he was doing it.

It must be that when one arrives at that level, things that they hadn’t been able to see before become visible, don’t they?

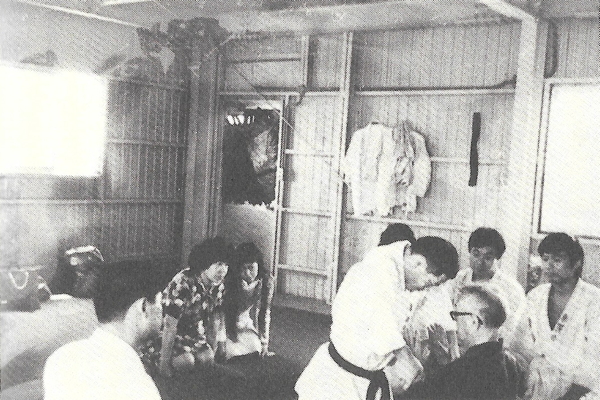

Hokkaido, 1974 – Aiki-age with Kodo Horikawa

Hokkaido, 1974 – Aiki-age with Kodo Horikawa

Published by: Christopher Li – Honolulu, Hawaii

Muko Nishida with Mr. and Mrs. Horikawa in Hokkaido, 1973

Muko Nishida with Mr. and Mrs. Horikawa in Hokkaido, 1973 Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa

Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa Seated Thousand-armed Kannon Bosatsu

Seated Thousand-armed Kannon Bosatsu

Demonstration at Police Headquarters in November 1973

Demonstration at Police Headquarters in November 1973 Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa

Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu Kodokai Founder Kodo Horikawa The Aiki bodies of Sokaku Takeda and Kodo Horikawa

The Aiki bodies of Sokaku Takeda and Kodo Horikawa

Hokkaido, 1974 – Aiki-age with Kodo Horikawa

Hokkaido, 1974 – Aiki-age with Kodo Horikawa![Ueshiba-ha Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu [Spanish Version]](https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/wp-content/media/morihei-ueshiba-ayabe-1922.jpg)

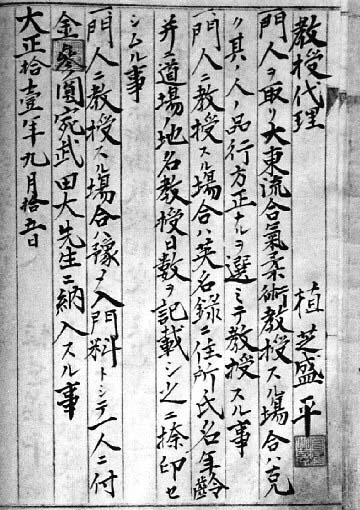

Certificado Kyoju Dairi Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu expedido a Morihei Ueshiba

Certificado Kyoju Dairi Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu expedido a Morihei Ueshiba Kisshomaru Ueshiba con su padre Ueshiba Juku en Ayabe, 1925

Kisshomaru Ueshiba con su padre Ueshiba Juku en Ayabe, 1925

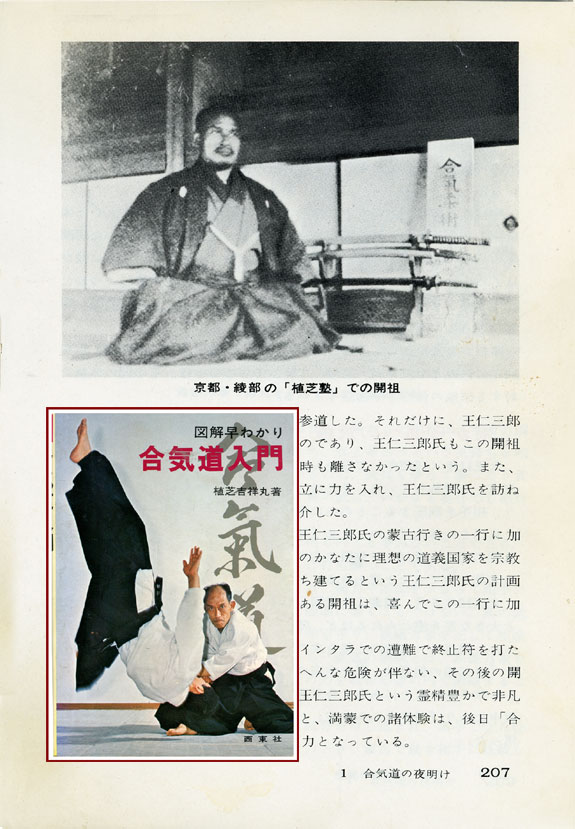

Aikido Shimbun, número 2 – mayo de 1959

Aikido Shimbun, número 2 – mayo de 1959 “Aikido Nymon”, de Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1975

“Aikido Nymon”, de Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1975 “Aikido Shintei” de Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1986

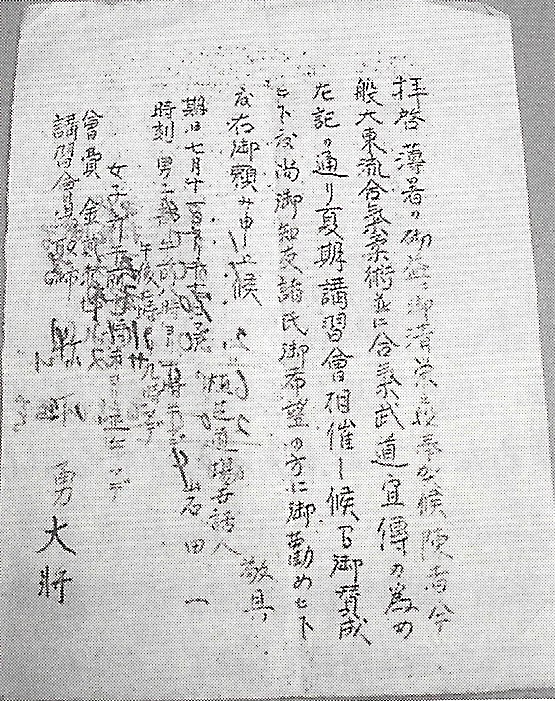

“Aikido Shintei” de Kisshomaru Ueshiba – 1986 Invitación para clases de verano con Morihei Ueshiba

Invitación para clases de verano con Morihei Ueshiba Sokaku Takeda en el Asahi Shimbun Dojo en Osaka – 1936

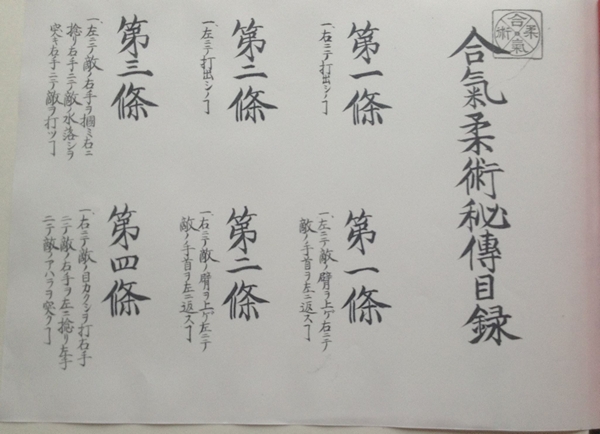

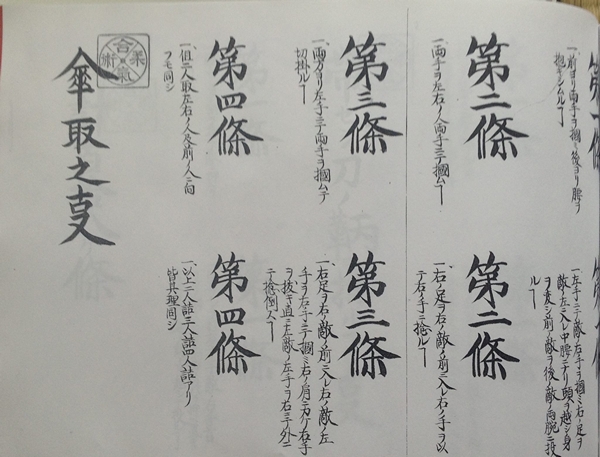

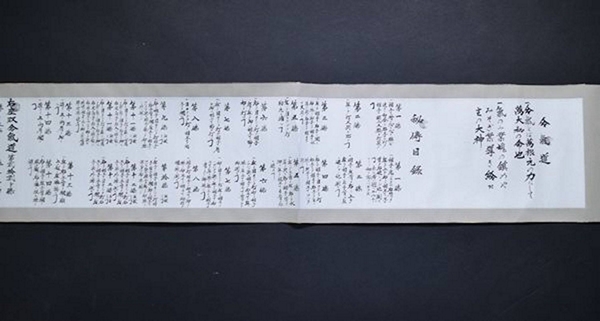

Sokaku Takeda en el Asahi Shimbun Dojo en Osaka – 1936 “Aiki-jujutsu Hiden Mokuroku”, 1925

“Aiki-jujutsu Hiden Mokuroku”, 1925

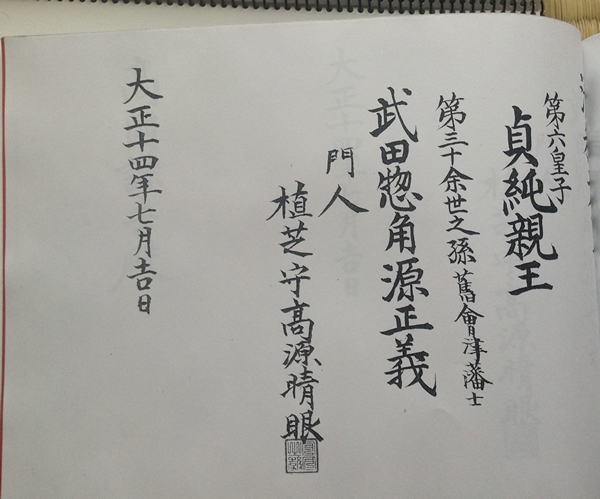

Hiden Mokuroku expide a Minoru Mochizuki en 1932

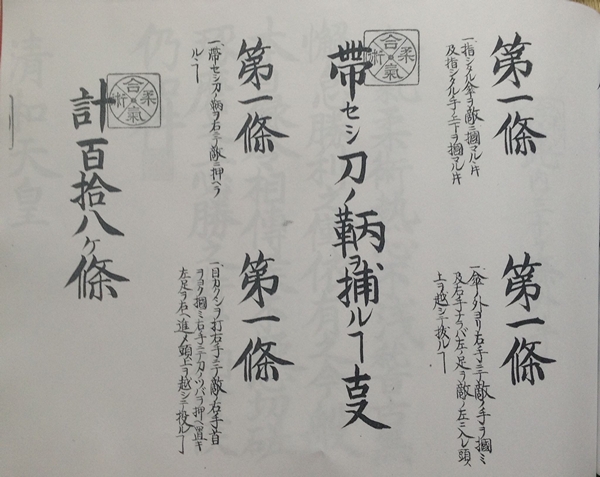

Hiden Mokuroku expide a Minoru Mochizuki en 1932 Aikido Hiden Mokuroku

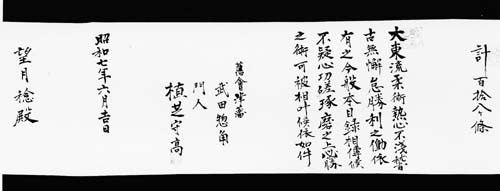

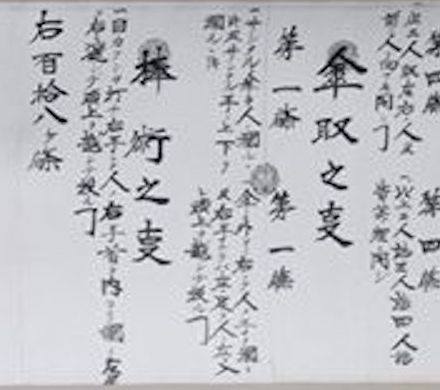

Aikido Hiden Mokuroku Aikido Hiden Mokuroku – detalle

Aikido Hiden Mokuroku – detalle