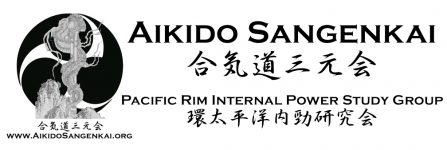

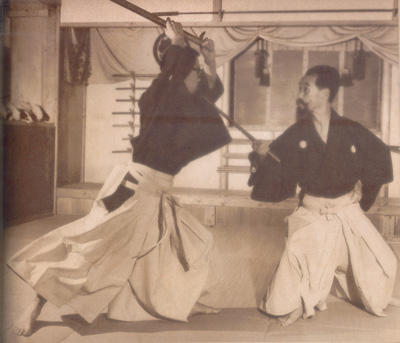

Director Akira Kurosawa observes Yoshio Sugino and Toshiro Mifune

on the set of “Yojimbo”, around 1961

Sometimes called “the Last Swordsman”, Yoshio Sugino (杉野嘉男 / 1904–1998) began his martial arts training in Kodokan Judo around 1918.

Becoming dissatisfied with Judo he began to train in traditional Yoshin Koryu jujutsu. Around the same time, in 1927, he also began to train in Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto-ryu with the four Katori Shinto-ryu shihan dispatched to the Kodokan at the request of Judo Founder Jigoro Kano.

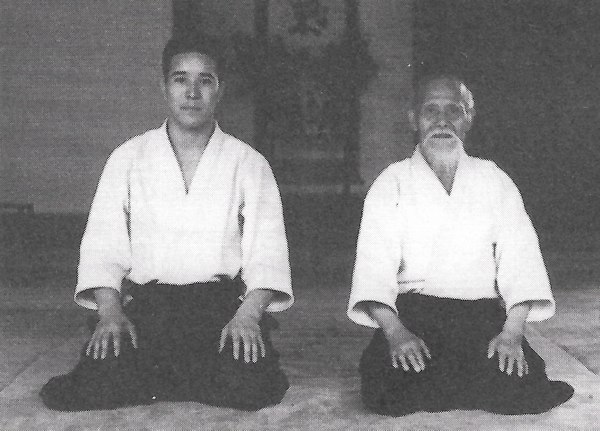

Around 1932 or 1933 he began training with Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba, and received a teaching license directly from the Founder in 1935. After the war his Aikido dojo in Kawasaki was the second official branch dojo of the Aikikai (Kuwamori Dojo was the first). Below he talks about his time with O-Sensei and with O-Sensei’s instructor Sokaku Takeda:

I didn’t consider aikido to be just an ordinary art…..Those practicing aikido today say that Ueshiba Sensei was really amazing but also wonder if what he did was actually true or not. They say such a thing because they have never seen his technique directly….I am lucky because I saw Ueshiba Sensei directly.

……………

Although Sokaku Takeda Sensei seemed to have the type of body which could be easily knocked over, his demonstration was extraordinary. He was capable of easily throwing 4th and 5th dan holders of the Kodokan.

– From “Interview with Yoshio Sugino” by Stanley Pranin

Sugino Sensei would later become well known for his work as a choreographer of fight scenes for many famous movies and plays, including Akira Kurosawa’s “The Seven Samurai” and “Yojimbo”.

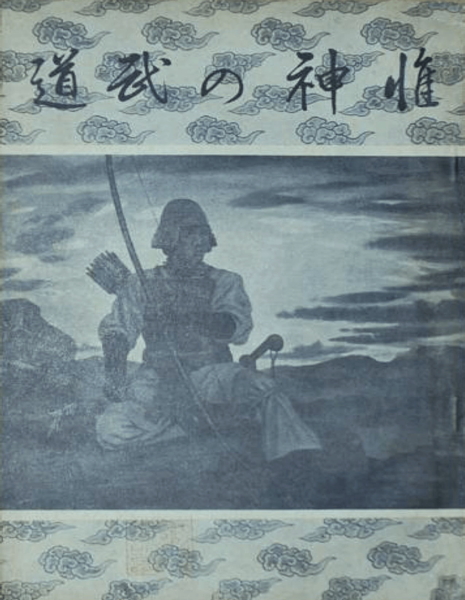

What follows is an interview with Yoshio Sugino (杉野嘉男) and his son Shigeo Sugino (杉野茂男) that originally appeared in Japanese in “Kengo Retsuden-shu” (Biographies of Kendo Masters) number 67 Futabasha Publishers Ltd. (剣豪列伝集 67号 双葉社 1961年), 1961. This is the same year that the movie “Yojimbo” was released.

Yoshio Sugino (杉野嘉男)

Interview with Yoshio Sugino of Katori Shinto-ryu, 1961

A visit to the “Gyaku Nuki no Tachi” (“Reverse sword draw”)

Morikawa: You showed us a variety of Ken-jutsu. That list of techniques, starting with Gyaku Nuki no Tachi (逆抜きの太刀), Torii no Kamae (鳥居の構え), Ko-gasumi (小霞), O-gasumi (大霞), Shin no Kamae (心の構え) and others, are completely distinct from other schools, aren’t they? They eliminate the two steps of deflecting a sword coming to strike and then counter-attacking – you feint a reception and then the opponent is stabbed or cut directly in that same movement.

“In one startling early scene in Yojimbo, for example, Mifune’s samurai character provokes three local rogues into drawing their weapons, whereupon he explodes into action and cuts all three down, using movements so swift that the eye can barely follow. The technique Mifune used in this scene (called gyakunuki no tachi) is a particularly difficult one in which the blade is drawn with the right hand using a reverse grip, brought over the head, reversed and brought down again in another cutting motion. But Mifune carried it off with such explosive precision that even Sugino could not help but be impressed.”

– The Last Swordsman: The Yoshio Sugino Story, by Tsukasa Matsuzaki

Gyaku Nuki no Tachi / 逆抜きの太刀

Yoshio Sugino: That’s right. That is a specialty of Katori Shinto-ryu, one of the inner teachings. One feints a reception and the sword of the receiver cuts the attacking sword directly with that same movement. In actual combat the attacker is controlled that much faster, with that little waste.

Morikawa: Ken, yari, kodachi, bo, shuriken – you use many different things, are they all from Katori Shinto-ryu?

Shigeo Sugino: That’s right. In all Shinto-ryu there is only one foundation, that just changes depending upon the weapon being used.

Morikawa: Previously I met Shimizu Shihan (Translator’s Note: Takaji Shimizu, the 25th Soke of Shinto Muso-ryu) of the Tokyo Police Department. Shimizu Shihan did many different things, such as jo, kusari-gama (鎖鎌), and hojo-jutsu (捕縄術 – police techniques for tying with rope), but they all came from different schools.

Yoshio Sugino: That’s right, in the case of Mr. Shimizu. He has already been an acquaintance of mine for more than thirty years, and he has mastered each school. In my case the difference is just in Judo, Aikido and kusari-gama. Judo was with the Kodokan, and of course Aikido was with Ueshiba Shihan – when I was studying it was still called Daito-ryu Aiki-jutsu.

Morikawa: I was astonished that you could learn so many really different things at one time. If we studied for a lifetime it’s likely that we wouldn’t be able to do it. Does your family have a heritage of generations of Katori Shinto-ryu swordsmen?

Yoshio Sugino: No, sword is something that I just built in my generation. I have heard that there was a master of the sword some generations ago, but my family were farmers from Naruto-machi Sanbu-gun (武郡成東町) in Chiba Prefecture. We had a large estate and were given the right to a take a surname and bear a sword (苗字帯刀), so we took the name Sugino.

Torii no Kamae / 鳥居の構え

Iizasa Choisai Ienao (飯篠長威斎), Founder of Japanese Kendo

Morikawa: What kind of Shihan did they have in Katori Shinto-ryu?

Yoshio Sugino: They were all top class famous swordsmen. I was trained by four Shihan named Ichizo Shiina (椎名市蔵), Narimichi Tamai (玉井済道), Tanekichi Ito (伊藤種吉) and Sozaemon Kobuki (久保木惚左衛門) (Translator’s Note: these were the four Shihan dispatched to the Kodokan at the request of Jigoro Kano). I went to the dojo in Chiba myself or had them come to my home, I also learned Shinto-ryu bo-jutsu at the Kodokan. After I opened a Judo dojo in Kawasaki I had them come there and trained seriously. For generations the Soke took the name Iizasa Shuri-no-Suke, but at that time Shuri-no-Suke Kinjiro had passed away in his youth and there was no other Shihan. Now the son of Mr. Kinjiro has succeeded him, but he is still a youth in his twenties. However, in the end breeding will tell, so I believe that he will become a top class swordsman worthy of being called a master.

Morikawa: Speaking of Iizasa Choisai, he is someone who left behind achievements great enough to call him the founder of Japanese Kendo, you must think that he was a great swordsman.

Yoshio Sugino: Of course, that’s so. Any historian would call him the founder of Japanese Kendo. Correctly he was Iizasa Iga-no-Kami Ienao (飯篠伊賀守家直), Choisai is the name that took after he secluded himself in the mountains and became a Buddhist monk. He was born in Shimo Katori-gun Iizasa Mura (下総香取郡飯篠 – currently Tako-machi in Chiba Prefecture). In the beginning he served the Ashikaga Shogun Yoshimasa, but his opinions were ignored so he resigned and went to Kanto. There he served the Chiba family, but after they declined he rejected the world, retreated to the mountains and set his sights on Buddhist training. While he was serving the Chiba family he built a small castle in Katori and became its lord. There were only around a hundred retainers, it was a very tiny lordship. At that time he divided all of his lands, assets and monies among the retainers and, penniless, left on his religious training. He was already past 60 years old. He prayed in Katori for one thousand days and one thousand nights, around three years, and then mastered the Way of the Sword.

Katori Jingu / 香取神宮

During this time he experienced a miracle in a dream, a divine message from the Kami “You must become a house for swordsmen, the Interim Reviver (中興の祖 / “Chuku-no-so”) of Japanese Kendo.”. His eyes opened to the secrets of the sword, he developed many students until he passed away in Chokyo year 2 (長享二年 / 1488) at the age of 102 years.

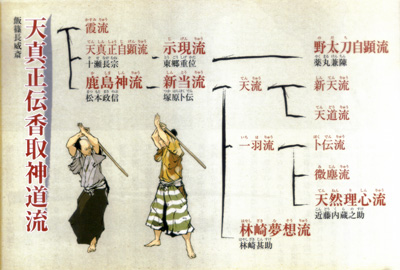

Among those students appeared many master swordsmen, such as Matsumoto Bizen-no-kami (松本備前守), Tsukahara Tosa-no-kami (塚原土佐守 – father of Tsukahara Bokuden), Kamiizumi Ise-no-kami (上泉伊勢守), Morooka Ippa (諸岡一羽斎), Iba Zesuiken (伊庭是水軒), and Itori Kyoun (井鳥巨雲). These each became top class pioneers, and that is why he became, literally, the Interim Reviver of Japanese Kendo.

He moved his residence to Baibokuzan Fudansho (梅木山不断所), on the grounds of Katori Jingu (香取神宮) and prayed earnestly for the divine protection of the great diety. Practicing sword day and night with the plum trees as opponents and shouting vigorously, he devoted himself single-mindedly to his training.

The correct name is Tenshin Shoden Shinto-ryu (天真正伝神道流). Because it began in Katori it is called Katori Shinto-ryu (香取神道流).

Morikawa: It is said that Choisai’s teacher was Kabuto Gyobu-no-sho (鹿伏兎刑部少輔), also there is a legend that his teacher was a Kappa (goblin) who lived in the ocean and was known as Tenshinsho (天真正). This is a kind of legend, but it goes to show just how strong Choisai was.

Shigeo Sugino: In any case, the schools that came from Shinto-ryu dominate most of the Kanto area, it was called the “one wing of Kanto” (関東一羽). In Kansai there was Chujo-ryu (中条流) and others that had formed separate schools.

Morikawa: Is that so? When looking at the line-up of students, Tsukahara Tosa-no-kami was succeeded by his child Bokuden, and from Bokuden-ryu Kamiizumi Ise-no-kami founded Shinkage-ryu (神影流). Matsumoto Bizen-no-kami Naokatsu founded Jikishinkage-ryu (直心影流), Morooka Ippa learned Shinto-ryu, and famous swordsmen like Iwama Oguma (岩間小熊), Tsuchiko Doronosuke (土子泥之助) and Negishi Tokaku (根岸兎角) came from among his students.

In any case, among the schools started after the middle of the Ashikaga period it can be said that there were none that escaped the influence of the three founders Chujo, Iizasa and Matsumoto.

Katori Shinto-ryu’s Lineage

Sugino Ko-tengu

Morikawa: Watching your son’s skills with the sword previously, I see that his sharpness is in no way inferior to yours. You must have trained him hard from the time of his childhood. How old is he now?

Shigeo Sugino: I was born in Showa year 6 (1931). I picked up the sword from the time I was around four or five years old. I trained with my father.

It was certainly difficult and strict, ferocious training. I would be awakened every morning while it was still dark, and doused with water in the winter. Sword, bo, naginata, kodachi, jujutsu, iai, shuriken, kusari-gama, I received training in it all. For that reason, before I entered elementary school I swung my sword in front of Prince Nashimoto-no-miya, and after that gave a demonstration of Katori Shinto-ryu to the Governor of Nara Prefecture. When the Hitler Youth group came a Nazi film crew recorded my presentation of Shinto-ryu kata in detail and took it home with them. That was when I wasn’t even yet ten years old. The pictures in this Katori Shinto-ryu manual come from that time.

Morikawa: Is that so? It’s truly a beautiful, wonderful kata. The kata of Budo are truly beautiful, aren’t they?

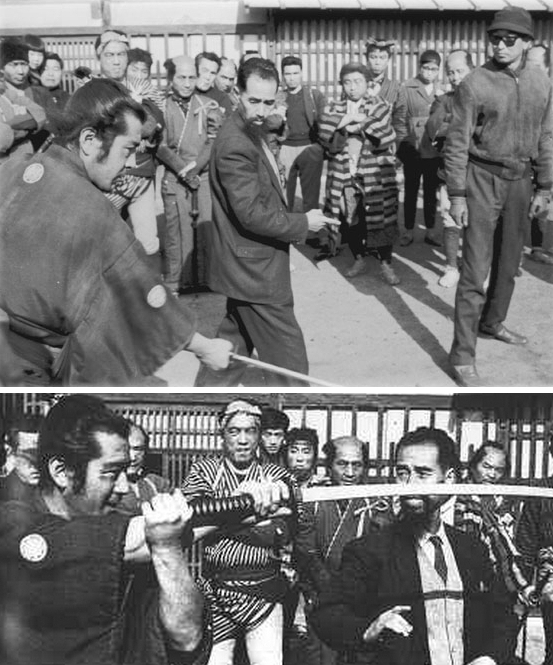

Part of a Kata in Katori-Shinto-ryu

Yoshio Sugino: Yes, they are. In ancient jujutsu they would say “Three years of randori, three months of kata”. It may be that a beginner who knows nothing will become strong after three months of randori. However, in the end that is no more than being the strongest of the beginners. Rather than that, they were saying that someone who does kata diligently for three months will be much stronger.

One can understand this if they consider the case of Go or Shogi, no matter how much a complete beginner can win at Go without studying tactics at all, a person who has researched a little bit of tactics will quickly become much stronger.

That’s how strong the tactics, or kata, of our predecessors are in absolute terms.

Etiquette (礼儀作法), flowers, tea, these were all the fruits of the study of the geniuses of the past, born from kata that seek the perfection of skill.

Life is all like that. If one doesn’t study this kata than nothing will develop. Even in baseball, tennis or golf I think that it is the same. In the end, the secret is to concentrate on one basic kata.

For that reason, those who disdain the kata of Budo, saying that they are old, that they have no meaning, are not qualified to discuss Budo. In that vein, art, sports, poetry, literature – all of these things require some qualifications to discuss them, don’t they?

Study the kata completely, and the move freely without being hindered by the kata. However, all of that is kata. This is perfection.

Morikawa: Perhaps this can be understood as Confucius’ “I follow all the desires of my heart without breaking any rule.”.

It may be that Confucius also arrived at that state of mind through intense life studies. In the end fencers must begin from Kata and pass through hard training in order to reach the perfection, beauty and flow of sword that is free of impediment.

Shigeo Sugino: That’s right. In sword as in life, if one is not serious then there will be no way that they can master the Gokui (“secret teachings”) that surpass life and death.

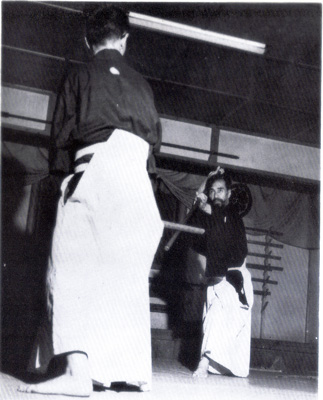

Katori Shinto-ryu Training

Yoshio Sugino: If we put it another way, tactics and Kata are the shortest route to reaching the Gokui. In order to learn and master this “mystic law” or “occult method” I had to go through very hard training in the past.

It is because Kendo is something psychological that those of the past who were called “Kensei” (“sword saints”), whether it was Tsukahara Bokuden, Isobata Banzo or Ito Ittosai, they all spent time alone in the mountains. Those swordsmen seeking to learn this all went to the mountains, first hauling water and gathering firewood. Serving their teacher earnestly they purified themselves and united their body and minds before becoming enlightened to the Okugi (“secrets”), inheriting them and passing them on to later generations as Kata.

Because there are profound depths inside each of these Kata they must not be neglected. They are absolutely something that should be cherished and passed on to future generations.

Next in importance is how one masters those Kata inside of oneself, in other words, how to digest them and make them your own.

Morikawa: In the end there is an individual personality within oneself, so one could say that the foundation is digested into one’s personality, or that one manifests their personality standing upon that foundation, couldn’t you?

Katori Shinto-ryu Kodachi (short sword)

Modern Budo is Sports

Morikawa: Speaking of the kind of Budo training upon which one stakes life and death, the spirit, mindset, and composition of the Budo of the past and the Budo of the present are completely different, aren’t they?

Yoshio Sugino: That is what I am trying to say! As far as I am concerned, Judo and Kendo are not Budo. They are sports. They have gone far away from the most important spirit of Budo.

Dan ranks, competitions, championship – the very existence of terms like these is ridiculous. They are clear proof that these are sports.

When one began to train in the past competitions were strictly prohibited, a violation meant that one would be expelled immediately. Further, the absolute secrecy of the methods extended even to brothers, fellow students. There was a Sempai/Kohai order among fellow students, the Sempai treating the Kohai with kindness, connected by humanity and justice (仁義), and by etiquette.

I wonder how it is today? One often sees XXX 7th Dan or 8th Dan written even on people’s business cards. Then, when they receive a higher Dan rank by recommendation – from that day they puff up their chests and put on a teacher’s face towards others. Things like that are not Budo.

Thinking of it from the fundamentals, in competition rules are defined in order to eliminate threats to one’s life. In Kendo one wears protective gear. Face, hands, torso, however much one strikes outside of the specified areas – in other words, in the areas with no protective gear, one can never score a point. For that reason one can fight freely, with complete freedom, safely and without feeling fear for one’s life. In Judo one wears a Judo-gi and engages in matches limited to a single form. One cannot hold a weapon. What is limited by rules is already a sport. In the end, because there is no danger to one’s life, any cowards can relax and throw each other at ease.

But the true nature of Budo is different. Keeping in mind crossing live sword against live sword, this is the foundation from which it was born, originally one’s life was in danger. For that reason, one was always confronting life and death. In that instant one leaps to grasp a mental state in which the mind is completely focused on one point. In religious terms one reaches a mental state of release from the bonds of birth and death (生死解脱), and one can swing the sword free of impediment. For that reason, competitions were not encouraged, or possible. If one did then there were no alternatives other than taking the other person’s life or dying oneself. At best, one would be crippled. Fights with live swords from this period, with the exception of cases with an extreme difference in skill, usually ended in a single breath. It was certainly nothing like what is seen in movies or on the stage. There is no doubt that it was simple, with very little movement.

Shigeo Sugino: That must be true. For example – even if one wears protective gear on their face and hands like Kendo, when they face off with a bokuto they will suddenly become unable to move. That is because they feel the danger to their life. Further, the final deciding fact in Shinto-ryu is kesagake (“diagonal cut from the shoulder”). Under the rules of Kendo one cannot score a point with kesagake. There are these kinds of absurdities. Everyone aims for the head, and in order to aim for the hachigane (“forehead protector”) they lift their heels. Doing this they will be unable to seat their hips at all, it is unusable in a real fight. In other words, when one imposes the limitations of rules they become captive to them. One becomes obsessed with scoring points, and the root of Budo technique is destroyed. Actually, rather than aiming at the hachigane, aiming for the face guard is far and away more effective.

Yoshio Sugino: As I said before, in Shinto-ryu one does not receive the other’s sword, the moment of receiving is left out and one just cuts directly. If one thinks of facing off in a real fight with live swords then perhaps they may understand. If one actually draws a live sword and thrusts it in front of the eyes the tip of the blade is very frightening. There one discovers how to get through this. In an actual fight there is no time to receive. One does not know how the opponent will change and come at you next. Therefore, we cut the opponent directly from a receiving posture. I taught it just like that in “Yojimbo”. If you observe the flash of the sword when Toshiro Mifune (三船敏郎) cuts Jerry Fujio (ジェリー藤尾) you will understand. I think that it is because he cut without receiving that it has the impact and flavor of an actual confrontation.

Training in Katori Shinto-ryu

Great Actors (名優) and Sword Saints (剣聖)

Morikawa: It came back to me with Yojimbo, but I heard that you have taught sword techniques for many movies and plays.

Yoshio Sugino: Yes, the first time was at the Zenshinza (Translator’s Note: 前進座 a Kabuki theater in Tokyo, built in 1935), when they were performing “”Bansuiin Chobee”” (幡随院長兵衛). Kanemon (翫右衛門) was playing Jurou Zaemon (十郎左衛門) in the scene when Chobee was stabbed and killed in the bath, and I taught them their stances. Next was in “Takadanobaba no Adauchi” (高田の馬場の仇討) at the Zenshinza, with Kanaemon playing Nakayama Yasubee (中山安兵衛). By the way, their sword techniques were exactly the same as those performed by Shodai Danjuro (初代団十郎) and Kikugoro (菊五郎), not even a little bit close to real sword. The Shodai Danjuro of that time felt that preserving the sense of the past was what he wanted, preserving the spirit of the first Danjuro. But if the spirit is not there, then no matter how much you watch all that is left is the old form. That was no good, so I taught them an actual Kata. Then their own style of fighting must have emerged. Not just sword Kata, their own individual spirit was infused wonderfully. As one would expect, I admired them as great actors. At that time I also taught the Naginata of Nagatsugawa Yuhan (中津川祐範) to Bando Choemon (坂東調右衛門). More recently, I taught the sword techniques for the cutting of Sakamoto Ryoma (坂本龍馬) at the Zenshinza.

Morikawa: Did you have a difficult time with the movies?

Yoshio Sugino: During the time of “The Seven Samurai” (七人の侍). At the time there were no fight scene choreographers, so the Director Kurosawa did it all by himself. I thought that was really difficult. Especially, Seiji Miyaguchi (宮口精二) was doing a period drama (時代劇) for the first time, and didn’t even know how to hold a bamboo sword, so he came to my dojo by himself. I taught him specially, and Miyaguchi-san’s sword technique ended up receiving the best reviews. In “The Last Princess” (隠し砦の三悪人), Susumu Fujita also came to visit me, and here you can see his enthusiasm.

Morikawa: Many of them were from the Kurosawa group, weren’t they?

Yoshio Sugino: Yes. Inagaki Sensei’s “Ganryujima” (巌流島), “Duel at Ichijoji Temple” (一乗寺決闘) and “Yagyu Secret Scrolls” (柳生武芸帳) were as well.

Morikawa: Thank you for taking time out of your busy schedule.

Published by: Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI

When I was 9 I saw seven samurai, I was truly inspired by the film to follow a life in the martial arts, practicing judo, karate and kenjutsu I will be forever indebted to the Tenshin shodan katori ryu.