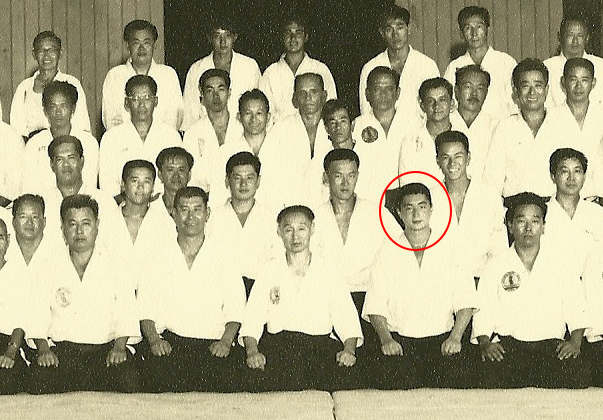

Yoshimitsu Yamada in Kauai Hawaii, 1966

What was Jigoro Kano thinking, anyway?

The other day I was reading an interview with Yoshimitsu Yamada on the Aikido Sansuikai website. This passage happened to catch my attention:

Well, the ranking system in aikido is another headache. I personally disagree with this system. A teaching certificate is okay, a black belt is okay. But after that, no numbers, no shodan, no nidan, etc. People know who is good and who is bad. The dan ranking system creates a competitive mind, because people judge others – “oh, he is sixth dan, but he is not good, this guy is much better…”

Yamada has made similar statements before, I know, but it’s always interesting when the person responsible for handing out rank to a large number of people in several countries states publicly that he is himself opposed to the ranking system.

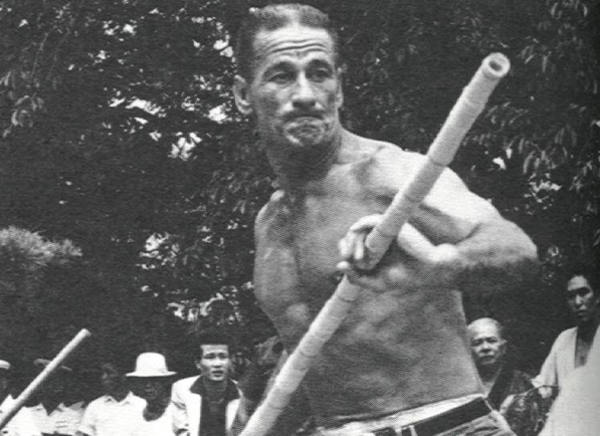

Donn Draeger – martial arts coordinator on the set of

the James Bond film You Only Live Twice (1967)

– the first non-Japanese to enter Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū

Tenshin Shōden Katori Shintō-ryū (天真正伝香取神道流) is the oldest organized martial tradition in Japan, dating from 1447.

You may ask how Katori Shintō-ryū is relevant to Yoshimitsu Yamada’s interview, and here it is – no ranks.

For over 400 years, there were no ranks or ranking systems, no black belts, in the traditional Japanese martial arts.

Somehow, these arts survived, and even prospered.

All that ended when Judo Founder Jigoro Kano adopted the Dan ranking system into Judo and promoted Shiro Saigo and Tsunejiro Tomita to Shodan in 1883. This ranking system would rise to great popularity in the pre-war era, eventually becoming adopted by virtually all of the modern (and many of the not-so-modern) Japanese martial arts.

Prior to that, for over 400 years, there were no ranks – no Black Belts in Japanese Budo.

Until the modern introduction of the ranking system in 1883 (and almost 60 years later than that for Aikido) people got by with a “Menkyo” certificate system that showed a persons qualification in the Ryu.

Morihei Ueshiba was a participant in such a system under Sokaku Takeda in Daito-ryu.

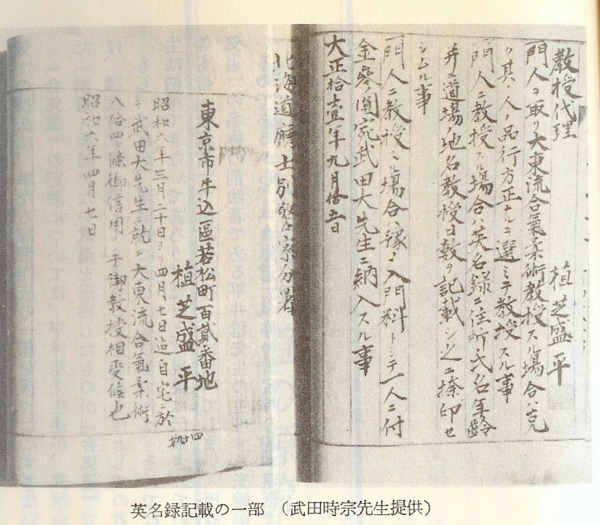

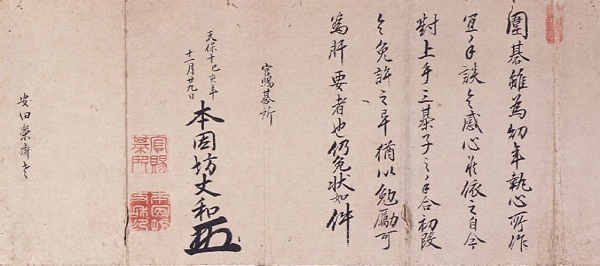

Sokaku Takeda’s Eimeiroku

Sokaku Takeda kept an “Eimeiroku” (英名録), in which each student’s study was recorded, along with a record of any licenses granted to that student.

For example, the page on the right above shows the awarding of the Kyoju Dairi (Assistant Instructor) license to Morihei Ueshiba in 1922. The page on the left is from 1931 and records that Sokaku Takeda taught Morihei Ueshiba the 84 Goshin’yo No Te techniques for 20 days at Ueshiba’s home in Ushigome (now Wakamatsu-cho).

Goshin’yo no Te (護身用の手) was the highest level scroll awarded at the time that Morihei Ueshiba was training under Sokaku Takeda.

Most of Morihei Ueshiba’s pre-war students (Minoru Mochizuki, Rinjiro Shirata, Kenji Tomiki, for example, among others) also received some version of these scrolls.

Then – the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai (大日本武徳会) happened along.

The Dai Nippon Butoku Kai was organized under the authority of the Japanese Ministry of Education, and was tasked with standardizing and regulating the traditional Japanese martial arts.

The Dai Nippon Butoku Kai, for example, was responsible for the adoption of “Aikido” as the name for Morihei Ueshiba’s art.

Along with the name change came the standard Kyu-Dan ranking system established by Jigoro Kano, already in use by many other martial arts in Japan.

Both the name change and the Kyu-Dan ranking system were implemented by Morihei Ueshiba at the behest of the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai in the early 1940’s.

1) This means that many of Aikido teachers instructing today are actually older than the so-called “traditional” ranking system as it is used in Aikido.

2) It also means that the “traditional” Kyu-Dan ranking system actually has no connection to traditional Japanese Budo – that it is a modern convention.

For his part, Ueshiba himself seems to have had a fairly cavalier attitude towards the modern ranking system.

For example, here’s Yamada’s opinion on what O-Sensei thought about these things:

Besides, I don’t think that O-Sensei agreed with that ranking system. To him the number doesn’t matter. Once when I was giving him a massage he said to me “Mr Yamada, what rank are you?” I answered: “I’m shodan,” and he replied: “So today I’m giving you sandan.” [laughs] Nobody believed that. I knew his personality and I didn’t take it seriously. I just answered “Thank you very much.” That is what happened.

Yamada’s not alone with this anecdote, I’ve heard the same or similar anecdotes from a number of people.

Yasuo Kobayashi (right) at the old Aikikai Hombu Dojo

Another post-war student from the 1950’s, Yasuo Kobayashi, related some similar incidents that occurred around 1958:

About this time there were the following incidents. People came from the countryside suddenly demanding an Aikido 10th dan license. This was because in the old days, when O-Sensei was teaching in the local areas, he would notice someone who, for just a moment, seemed to understand, and he’d say, “Oh, this guy’s got it. I’ll give him a 10th dan.”” It seemed he would easily say things like, “You’re great! Let’s make you a 9th dan,”” to people who took him at his word, even though they may bave been only a 3rd or 4th dan. That was one face of O-Sensei. He’d just say something like, “You’re a 9th dan or 10th dan,”” When I was younger, O-Sensei told me, too, many times, that I was a 9th or 10th dan. The other uchideshi were also “promoted” to 9th or 10th dan many times.

Mitsugi Saotome, another contemporary of both Yamada and Kobayashi, related a similar story to me, in which he was spontaneously “promoted” to eighth dan by O-Sensei after having had a particular moment of insight (he didn’t actually get promoted to eighth dan until much later, long after O-Sensei had passed away).

Shusaku Honinbo’s (本因坊秀策) Shodan Certificate in Go, circa 1840

When Jigoro Kano instituted the Kyu-Dan system of ranks he adopted a system that had been in use in Japanese Go since the 1600’s, when it was introduced by Dosaku Honinbo (本因坊道策).

Jigoro Kano was an educator by trade, and was actually director of primary education for the Ministry of Education (文部省) for several years. He was also deeply committed to the modernization of Japan’s educational system, which was in the midst of a transition from the traditional system of Temple Education (Terakoya Kyoiku / 寺子屋教育) to the modern Gakusei (学制) system of education modeled on Western educational methods which was instituted starting in 1872.

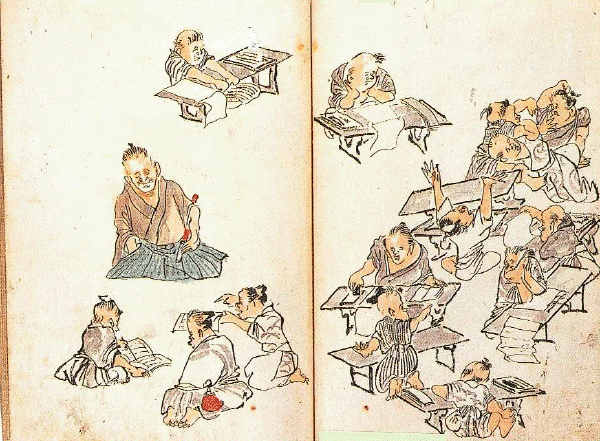

Temple Education in the Edo Period

Interestingly, Morihei Ueshiba, in something of a hang-over from the Edo Period, was sent to be educated at a Shingon Buddhist temple at the age of 7.

So…why didn’t Jigoro Kano keep the traditional Menkyo system?

1) Depending upon the particular Ryu, the Menkyo system consists of any where from two to eight or so certificates, with years (sometimes many years) between certifications.

This is well suited for adults, who have long attention spans and are committed for a training span measured in years, but not so much so for children.

2) Under the traditional Menkyo systems there is no system of visibly recognizing a person’s achievements in the art – the “gold star” of the colored belt system that has been adopted into modern ranking.

Again, well suited for adults, who are (or should be) more interested in learning an art than advertising their prowess around their waist, but not so much for children.

Especially not so much for children in a modern educational system, which is built upon a structure of grades, ranks and gold stars.

And that was really the focus and goal of Jigoro Kano – to bring Judo into the modern educational system as a complementary form of physical education.

Even the “black belt”, introduced three years after the Kyu-Dan system itself, may possibly have been adopted by Kano from a school system in which advanced swimming students were divided from beginning students by black ribbons worn around their waists.

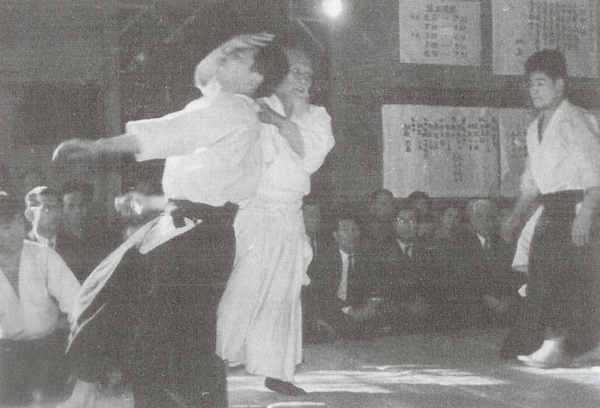

Moshe Feldenkrais demonstrates Judo with Mikonosuke Kawaishi in Paris, 1938

The system of colored junior belts (for example, white → yellow → green → blue → brown → black) wasn’t invented in Japan at all – it was introduced in Europe in 1935 by Mikonosuke Kawaishi, who was instrumental in spreading Judo to there and then later brought back to Japan. The color scheme made it easier for the students to re-dye the same belts.

Again, it was a system that was introduced for…children, and it worked well…for children.

(Note: Demetrio Cereijo notes that the colored belts may actually have been introduced in the London Budokwai by Gunji Koizumi around 1927 and later popularized by Kawaishi)

For adults and as adults, I think that most of us have some experience with the negative aspects of the ranking system. Some of us have a lot of experience with those negative aspects.

The question then becomes – what do we, as adults, get from such a system, and is it worth the price we pay?

If your answers are similar to mine, then the question may become – why don’t we just get rid of it, as Yamada himself suggested?

Of course, most organizations encourage the existence of a ranking system.

In organizational terms it makes sense – Aikido is no longer a single source art, it’s available pretty much anywhere, and if you don’t like one group then you can join another with relatively little trauma.

There’s really only one point of control these days that an organization, dojo or instructor has over their students, and that is the dispensing of rank.

Controlling who gets rank and when is the one and only control mechanism over their students outside of the will of the students themselves.

Someday it may be people will wake up to the fact that this entire mechanism is imaginary – it only works when those in the system permit themselves to buy into the premises made by the system itself.

Also making sense in organizational terms are the financial aspects.

Most large organizations (and even many small ones) survive in some large part off of the testing and promotion fees proffered by their members, which can run into the thousands of dollars for some promotions.

When Jigoro Kano introduced the modern Kyu-Dan system he also opened the door to a potentially difficult to ignore income stream for both martial arts schools and martial arts organizations.

Which brings us right back to the first question – what do we get from such a system, and is it worth the price we pay?

Personally speaking – twice I’ve made the decision to step out of the ranking system, and twice I ended up getting drawn back in, so I don’t really have any good answers.

Both times that I ended up getting drawn back in it was for the same reason – the sad fact of the matter is that most people in conventional Aikido treat you differently according to your rank. This despite the fact that most people also talk about how rank doesn’t really matter.

Because I have some particular rank people may ask my opinion about Aikido – but the guy standing next to me with a third kyu just gets ignored.

Never mind that the third kyu can kick my butt all day long – what could anyone possibly learn from a white belt?

Published by: Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI

![Aikido, qué no sabemos y por qué no lo sabemos ... [Spanish Version] 武産合気](https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/wp-content/media/takemusu-aiki-hideo-takahashi.jpg)

Leave a Reply