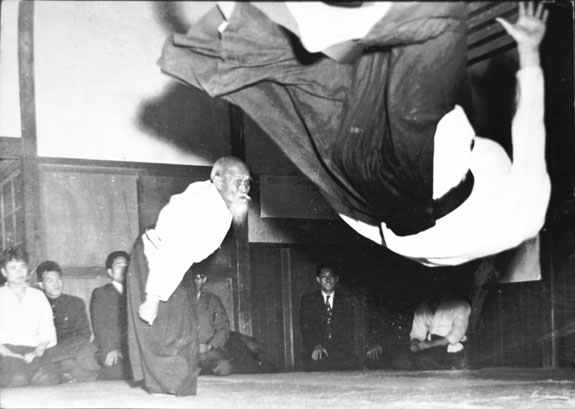

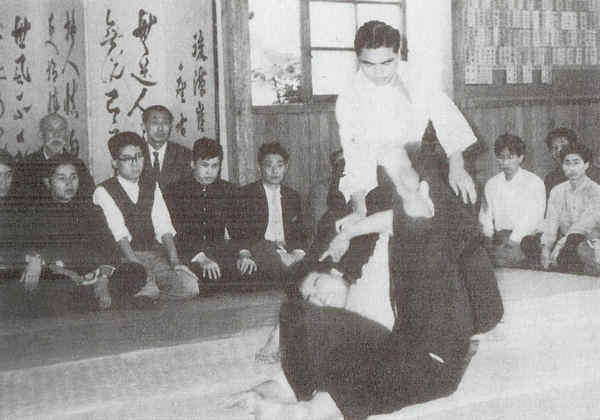

Hiroshi Tada, 6th Dan, being thrown by Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba O-Sensei (1958)

“Ueshiba Sensei of Aiki-jutsu is the greatest Budo master alive”

Hiroshi Tada was born in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan December 13th 1929. He began training at Aikikai Hombu Dojo on March 4th 1950. He was sent to Rome, Italy in October 1964 and established a dojo in 1966. He was Instrumental in the growth and development of Aikido in Italy.

Until he left for Europe in 1964 he also studied breathing exercises and yoga with Tempu Nakamura, who is well known for his influence on Shin-Shin Toitsu Aikido (心身統一合氣道) Founder Koichi Tohei.

He also studied with the Ichikukai (一九会), which was founded to continue the teachings of Tesshu Yamaoka by his student Tetsuju Ogura. The “1-9” Group was named to memorialize the day of the month (the 19th) on which Tesshu died, and is famous for its rigourous Misogi training.

Hiroshi Tada later developed his own system of breathing and meditation exercises called Ki no Renma (気の練磨 / Cultivation of Ki) as a supplement to Aikido Training.

The following article is a translation of the Japanese article that originally appeared in “Aikido Tankyu” (合氣道探求 / Aikido Quest), a magazine published by the Aikikai Hombu Dojo.

Aikido Tankyu Issue 4 / 合氣道探求第4号

The Day I Entered Ueshiba Dojo, by Hiroshi Tada

(English translation by Christopher Li)

The first time that I heard Ueshiba Morihei Sensei’s name I was in the third or fourth year of elementary school. I heard it from my father’s close friend Yano Ichiro (former president of Dai-Ichi Seimei) while sitting at the dinner table. Mr. Yano was highly ranked in Kendo, and was also the chairman of the All Japan Businessman’s Kendo Federation (全日本実業団剣道連盟) at one time.

“Ueshiba Sensei of Aiki-jutsu is the greatest Budo master alive. He is incomparable as a Budoka.”

Saying this, he went on to describe his impressions of the training he had received from Ueshiba Sensei.

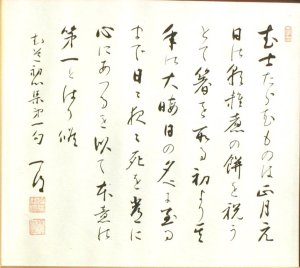

A passage from the “Budo Shoshinshu” written by Yano Ichiro

for the 30th anniversary of the All Japan Businessman’s Kendo Federation

In the past a Kyudo system called Heki-Ryu Chikurin-Ha Ban-Ha (日置流竹林派蕃派) had been handed down in our family, and my father had received extensive training from my great-grandfather from an early age. So he and Mr. Yano would often discuss Budo, and he had a great interest in this thing called Aiki-jutsu.

In my child’s heart I dreamed that one day I would be able to meet and learn from such an adept. Regretfully, with my father’s being called up for military service, the war, and the death of my mother, many events prevented this from coming to fruition.

In Showa year 25 (1950), five years after the end of the war, every inch of Tokyo was still covered with battle scars and burned out silhouettes.

Most Japanese of that time lived at the mercy of the waves of each day, while possessed of a foolhardy courage and an odd sense of the transience of life that would no longer surprise me. I, on the other hand, devoted my self to my daily Karate training in an attempt to extinguish the recurrent feeling that some part of my sprit was lacking. It was at that time that I recalled the talk of Ueshiba Morihei Sensei and Aiki that I had heard from my father and resolved to seek out more information.

One day after training, for some reason the conversation turned to Ueshiba Sensei and Aiki. Furthermore, according to an acquaintance of Mr. Takeda, who was captain of the Waseda University Karate Club, the Ueshiba Dojo was in Ushigome Wakamatsu-cho. This was quite nearby Waseda. I embraced my misty aspirations and enthusiastically made my way to Ueshiba Dojo to see Ueshiba Morihei Sensei, who was said to be an incomparable master.

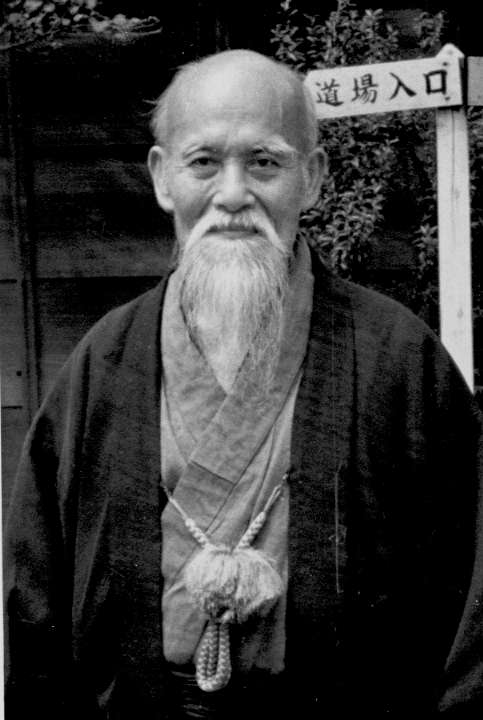

Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba O-Sensei, around 1955

in front of the entrance to the old Ueshiba dojo

Fortunately, the Ueshiba Dojo had been spared from war damage. When I entered the stone gate the dojo was on the left and directly ahead was a sliding glass door to a wide entrance. There was no one in the dojo, and when I asked at the entrance a young woman came out. It was the current Aikido Doshu Ueshiba Kisshomaru’s wife Sakuko. I don’t remember the details after I asked permission to enroll, but I think that I asked a lot of questions.

Even now I clearly remember the answer that Mrs. Ueshiba gave to my discourteous questions.

“When you see father you will understand what Aiki is.”

Then she explained that he was traveling, but would return to Tokyo in two or three days.

“I think that people will be coming for training soon”, she said, as she let me in to the dojo.

The dojo was 60 tatami mats in size (*one tatami mat is about 3′ x 6′), each with a Ryukyu-Omote (*a finely woven tatami cover), in spots the tatami was worn, an area of about 40 mats, and the rest were surrounded by gleaming black wooden planks. There were thick cross beams on the ceiling, at the front was a Kamiza about 12 inches high, 18 feet wide and 6 feet deep (高さ一尺、巾三間、奥行一間), and there was a large hanging scroll with a dragon’s face painted on it. To the side of the Kamiza was a bokuto rack with a few jo and wooden bayonets mixed in. On the right hand wall the name tags of the students were lined up, with a large clock in the middle. Under that was the student entrance.

After waiting for a short time, a brawny youth of some height wearing a blue Kendo-gi and a hakama and a small older man began training. The youth was a Kendo 5th Dan, the Waseda Kendo Club captain Kikuchi Tokio (now living in Otake and Kamaishi), and the other person was Kikuchi Ban, who had entered the dojo a little while before. As I watched them performing Katate-dori Tankan Kokyu I thought that this was different from any Budo that I had known before. That is, to assimilate the opponent’s power into the flow of your own power, to change your body to become one with your partner through rational movements, I felt that here was a different conception of Budo.

Ueshiba Morihei Sensei returned to Tokyo about four days after that. At that time, the official practice with Waka Sensei (now Ueshiba Kisshomaru Doshu) was for one hour from 6:30 in the morning. There were still only a few people, but everybody was passionate about training, and we would continue to train for as long as we were allowed.

That morning we had trained again past 10:00, and when we went out to the avenue at Nuke-Benten we saw two people who seemed to have just gotten off the departing Toden (*Metropolitan Electric Railway), one in Kimono and one wearing a student uniform. Kikuchi Tokio-san said, “O-Sensei had returned. Tada-kun, come here.”, and I ran foward. When Kikuchi-san had finished his greeting he introduced me, “Sensei, this is Tada-san who has just entered the dojo”.

I bowed, and when I lifted my head I saw that Sensei was staring at me intensely in my student uniform. Taking off his hat, he said, “I am Ueshiba”, and bowed courteously, astonishing me. There, seeing the great teacher that I had heard about for so long in front of me, I didn’t understand quite what – but seeing a dream that I had held in the depths of my heart for so long appear in front of me filled me with a wondrous emotion.

Sensei was only as tall as my chest. He had a face filled with deep crags, high cheekbones and a large nose. I thought that his large clear eyes had a slightly odd color. His long white beard fell over the lapels on his chest. We took Sensei’s Otomo, Kamizono-san from the Waseda Science and Engineering Department, from the avenue down to where the small road turned and saw him off.

The next day, Ueshiba Morihei Sensei’s training began with prayers to the Kami. None of those who have received Sensei’s teachings can forget the resonance of those Shinto prayers echoing through the dojo. When I envision Sensei as I saw him from behind at that time, I feel clearly that Sensei’s divine techniques were born through communion with the Kami.

Sensei came to the center of the dojo while rolling up the sleeves of his keiko-gi, and stretched out his hand to one of the students lined up in front of him. That person stood up and stepped forward as if pulled by a magnetic force, and as I saw him grasp hold of both of Sensei’s arms he was already being thrown. Sensei threw the students one after the other and then stretched out his hand to me as well. I stood up and stepped forward, but even as I thought to grasp both of Sensei’s hands with all of my strength I was already falling down. While all of this was happening Sensei was completely silent. Sensei’s training often began in this manner. When I first entered the dojo I thought that it was mysterious, that even with all the different kinds of training, that my sempai could understand even though Sensei did not say a word. However, over time I came to realize that those who could not understand what Sensei was doing without being told would not be accepted as students.

Sensei’s training brought a peculiar atmosphere to the dojo. It felt just as if the entire dojo would begin to breathe with Sensei’s breathing.

When I first received instruction, I felt “Ueshiba Sensei is an extremely advanced instructor”. It may seem a kind of awkward or impudent way of expressing my feelings toward Sensei, but here is what I mean.

At that time, the rumors of Ueshiba Sensei that were going around between the students at Waseda University were stories of something that was completely different from other modern Budo, that used actual fighting techniques from ancient jujutsu, of a bujutsu-ka of mysterious abilities whom modern sensibilities could not grasp – a great master from the ancient times of Japan who had appeared in this world.

However, when I actually met Ueshiba Sensei, in one sense he was much more modern than any other budo-ka or athlete that I had met up until that time.The stable rhythm of Sensei’s movement and its complexity and power left a strong impression, but more than anything else, even in the midst of movements that could instantly fell an opponent in an actual fight, was the warm atmosphere that enveloped the spirits of all those in the dojo. Perhaps I felt that, if human beings progressed, they would become like this Sensei.

Hiroshi Tada demonstrating at Ueshiba Dojo in early 1955

Kenji Tomiki seated in back in front of the folding screen

Hari Sunao seated in the right front on the right side

…………..And now, after 40 years, Aikido has spread to countries all over the world and gained in popularity year after year. I myself, twenty-some years ago, in the year of the Tokyo Olympics, went to Europe to spend several years disseminating and teaching Aikido, and have returned to train every year since then. When I look at Japan from the outside, I truly understand that it is the teachings of Ueshiba Morihei Sensei that have pointed out the Way of Aikido that has such power to tangibly express the traditional culture of Japan.

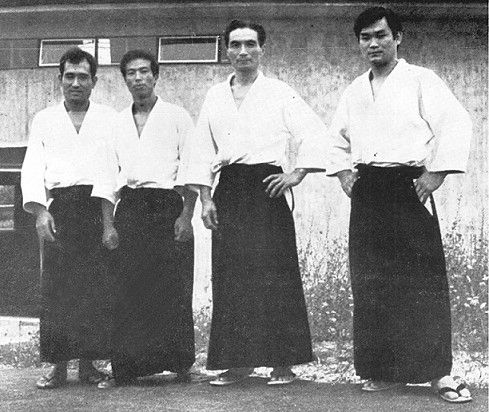

From left to right Masatomi Ikeda, Katsuaki Asai, Hiroshi Tada and Kazuo Chiba in May 1972

The practical expression of eastern philosophy that is so difficult to research in the competitive Budo that is now wide spread – the methods of training Ki/Mind/Body and the scientific training of technique in martial arts, combined as one indivisible training method, is a treasure of Aikido. It is because of this that Aikido can share a part in human research, and will grow ever further as we turn to the 21st century. I believe that we must pay careful attention to this point, and continue to increase and intensify our training.

(Hombu Shihan, Associazione di Cultura Tradizionale Giapponese = Founder of the Italian Aikikai – Head Instructor)

Published in “Aikido Tankyu” Number 4 – July 10th, Heisei year 4 (1992)

Afterword….

It is clear from the above that there was a steep learning curve involved in becoming a student of Morihei Ueshiba!

This was also mentioned in Stan Pranin’s interview with Hiroshi Tada on the Aikido Journal website – highly recommended for more information about this major figure of post-war Aikido.

Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI

Leave a Reply