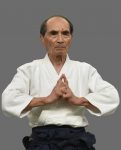

Hiroshi Tada Sensei in his twenties

Tatsuro Uchida interviews Hiroshi Tada Sensei

These three Budo “tips” came from Hiroshi Tada in a lecture that he gave in Italy in 2002:

1) An Aikidoka should be able to consistently cut down an opponent with the first blow. This it the true Budo aspect of Aikido. It is precisely because we are confident that we will always able to do this. This confidence gives us two things, our strength and the ability to choose a less deadly outcome, both of which we should have as a prerequisite to our training.

2) When you look at your opponent, he becomes the center of your Aikido, causing you to stop. When you practice, observe where your eyes tend to look. You should be the center of your movement, so when you move, you should see all around you. The question is how far can you see around you? half a meter? 1 meter? 3 meters? 5 meters? As far as your eyes can see, that is the sphere of your control. Once someone enters the sphere of your control, he is drawn to you as the center of that sphere. When O-Sensei would hold a session, one would notice that it was hard to see where he was looking, as if his eyesight was looking outside of the dojo.

3) A sword blade is useless if it is not moving. Once a blade starts moving, it should never stop moving or slow down too much. If an opponent can count the fingers on your hand (1,2,3,4,5) then it means you’re moving too slow. In the same way, once your tegatana starts moving, you should move in such a way that your opponent will never be able to count your fingers.

When I first met Hiroshi Tada at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo in 1982 he was quite a bit older than in the picture above, but his appearance was startlingly similar, and his gaze just as piercing as his tips for success above would suggest.

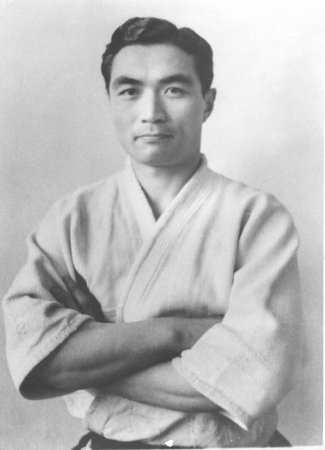

Hiroshi Tada at the 50th All Japan Aikido Demonstration in 2012

at age 82

Even at 82 his hair was almost the same shade of jet black, although the talk was that he never dyed his hair, kind of the Dick Clark of the Aikido world.

The following interview is a translation of an interview that appeared in “Eastern Body – Western Body” (Toyou no Shintai – Seiyou no Shintai / 東洋の身体・西洋の身体), a paper published in 1994 by the Kobe College Department of Intercultural Studies (神戸女学院大学総合文化学科).

Tatsuro Uchida

Hiroshi Tada is interviewed by his student Tatsuro Uchida, who is a professor at the Kobe College Department of Intercultural Studies and a somewhat controversial author, best known for “Nihon Henkyoron” (“Japan as a Peripheral Country” / 日本辺境論).

Before reading this interview, you may want to take a look at the interview with Hiroshi Tada that appeared in “Aikido Shihan Hiroshi Tada: The Day I Entered Ueshiba Dojo“, in which Tada describes his first meeting with Aikido Founder Morihei Ueshiba O-Sensei. Tada actually refers to that interview in this one.

The Budo Body: An Interview with Aikido Shihan Hiroshi Tada

(English translation by Christopher Li)

Interviewee: Hiroshi Tada (多田宏) born in Tokyo in Showa year 4 (1929). Graduated from the Waseda University School of Law in 1952. Aikido 9th Dan, Shihan of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo and the Gessouji Dojo, Founder of Associazione di Cultura Tradizionale Giapponese = Aikikai d’ Italia. Shihan of the Waseda University Aikido-kai (早稲田大学合気道会) and the Tokyo University Aikido Kirenkai (東京大学合気道気錬会), supervises Aikido Tada Juku (合気道多田塾).

Interviewer: Tatsuro Uchida (advisor to the Kobe College Aikido-kai / 神戸女学院合気道会, Aikido 5th Dan)

(at Aikido Tada Juku Gessouji Dojo / 合気道多田塾月窓寺道場, March 29th 1994)

Uchida: Thank you for taking time to speak to me today. Today I’d like to ask you in detail about your training (shugyo) experiences. Up until now we’ve only heard bits and pieces, but at this time if we could hear everything at once it would become a valuable resource not only for those related to Aikido, but for everybody in Budo.

There are several things that I would like to ask about today, one is concerning your training history in Budo, and another is to ask about the chance that you had to meet people with such unique supernatural bodies and spiritual abilities as Morihei Ueshiba (植芝盛平) and Tempu Nakamura (中村天風).

Tada: Did you read what I wrote about entering Ueshiba Dojo? (Note: the text that appeared in “Aikido Tankyu” was revised and distributed privately)

Uchida: Yes, I read it.

Tada: There are also a lot of things that I wrote for the Italian Aikikai… There was also something written by Kiichi Goto (former captain of the Waseda University Aikido-kai). (Note: “Profile of a Shihan” / 師範の横顔 ) (38) Aikido Shimbun number 208, May – Showa year 53 (1978))

Uchida: Yes, I read it. Today I would like to ask about some things that were not covered in those resources. I would like to begin with asking how your Budo Shugyo began in the first place.

Heki Danjō Masatsugu, Founder of Heki-ryu Kyudo (1443-1502)

-initiating Shigekata Yoshida into Kyudo (13th century)

Tada: When I was a child I went to do archery. We had a tradition in my family of a system of archery called Heki-Ryu Chikurin-ha Ban-ha (日置流竹林派蕃派), and my great-grandfather (Okiyoshi Tada / 多田興善) had passed it on to my father (Minoru Tada / 多田登). I learned that in the garden of our house in Jiyugaoka, with a makiwara as a partner.

Uchida: Sensei, were you born in Tokyo?

Tada: Yes, that’s right. I was born in the hospital of the Tokyo Imperial University in Hongou. I lived in Hongou Nishikata-machi until I was three years old. It was a place that my father had lived when he was a student and loved from that time. My father came from Kyoto University (Note: “Old Education System Third High School”, now Kyoto University) to Tokyo University.

Uchida: How old were you when you left Tsushima?

Tada: My grandfather (Tsunetaro Tada / 多田常太郎) was born in a compound in Izuhara, Tsushima. Later on he left the island and became a judge. Judges were transferred between districts every three years, so my father was born in Kii-tanabe. That is the same Tanabe where Morihei Ueshiba Sensei was born. Later on, my grandfather was transferred to Kyoto, with the Butokukai and many acquaintances, so my great-grandfather was very grateful to be in Kyoto. For that reason, my grandfather, who was devoted to his father, refused the three-year transfer four times, and stayed in Kyoto until my great-grandfather passed away.

Uchida: Your great-grandfather was the archer, wasn’t he?

Tada: We were originally samurai of the Tsushima-han. We followed the ancestors of the So clan feudal lords when they made a raid into Tsushima in 1245 and lived in Izuhara from that time, as chief retainers receiving 550 Koku (Note: 1 Koku is enough rice to feed one person for one year). By the way, there were some terrible incidents when we became entangled with elements loyal to the shogunate during the internal squabbles of the Kasshi Rebellion (Note: also called the Kinmon Rebellion and the Hamaguri Rebellion) as it was called in the Tsushima-han. Many perished in that incident, including my great-grandfather’s father, Tonoe Tada (多田外衛) and his 11 year old younger brother Sakujiro Tada (多田作次郎). My great-grandfather’s stout-hearted older sister Masu (満壽) took him and fled by boat so that the Tada lineage would be preserved. In the midst of winter on the Sea of Genkai they paid a sharp dealing fisherman of our domain and crossed by boat to the mainland. There they entrusted themselves to Motoni Nomura (野村望東尼) of Choshu. Masu had friendships with Shinsaku Takasugi (高杉晋作) and other loyalist patriots.

My great-grandfather was a master of archery, horsemanship, riflery and the sword. He became an officer in the cavalry of the imperial guards, but his health failed and he resigned, and by the time my grandfather became an adult he was a Shihan in archery and became the Shihan of the Kyudo Department of Kyoto University.

Great-grandfather did not transmit archery to my grandfather. They practiced, but it seems that my grandfather was not very good at letting go of unnecessary strength. Seeing that, great-grandfather immediately stopped teaching archery to my grandfather. I guess that the samurai of the past were like that. My father was quite strong, and my great-grandfather had high expectations and trained him well. He took him to the Butokukai many times, and it is said that from the time of elementary school to Kyoto High School and his graduation from Kyoto University they didn’t miss even one day of training.

I didn’t train that much in archery. Also, my father was called up for the military during the war so it wasn’t possible.

After I entered the university I began to train in Karate.

Uchida: Was style of Karate did you practice?

Tada: Shotokan.

Uchida: Shotokan? Then you must have know Shigeru Egami (江上茂) Sensei?

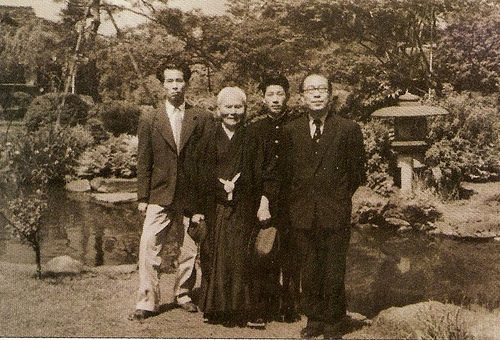

Shigeru Egami (left) with Shotokan Karate Founder Gichin Funakoshi (second from left)

Tada: Shigeru Egami-san was my senior (Sempai) at Waseda. Even if you call it Shotokan I think that it was a little different from today’s Shotokan. “Shoto” (松涛) was Gichin Funakoshi (船越義珍) Sensei’s pen name – Sensei never attached a name to the style of Karate that he practiced, but the students called it Shotokan-ryu. Later on, the Japan Karate Association (日本空手協会) was formed around those affiliated with graduates of the university.

Uchida: So, you also met Gichin Funakoshi Sensei?

Tada: Yes, I met him many times, and was privileged to receive instruction from him. Also, when Sensei came to the training at Waseda someone would escort him back to the streetcar station in the back of Okuma Kodo (Okuma Auditorium at Waseda University), and I would sometimes be selected for that role. Before getting on the streetcar we would get a snack at a small Taikoyaki (Note: also called “Imagawayaki“) place just excavated after the damage from the war. When he got on the streetcar after that he would turn right around, remove his hat, and say “Thank you very much, it’s okay now, please return home” politely and bow.

After that I entered Ueshiba Dojo and took Morihei Ueshiba Sensei as my teacher. I had often heard of Ueshiba Sensei from my father and his friends from the time that I was a child. As I said before, the events surrounding my entrance to Ueshiba Dojo are as I have written previously. I searched for Ueshiba Dojo for a long time, but I couldn’t find it. Then I made the acquaintance of a Mr. Takeda who was captain of the Waseda Karate Department at the time. There was also someone there who had a book by Ueshiba Sensei that had been illustrated by a Miss Kunigoshi (Note: Tada is referring to “Budo Renshu“). He knew a lot about the household of Ueshiba Sensei, and told me of number 102 Wakamatsu-cho.

Uchida: You didn’t even know where the dojo was?

Tada: That’s right, I didn’t know. No matter who I asked, nobody knew. Tokyo was a burned out field, after all.

Uchida: Was Morihei Ueshiba Sensei living in Iwama at that time?

Tada: He lived in Iwama, but he was busy traveling to Tokyo, then Kansai, then Tokyo, then Iwama again, in that manner.

Christopher Li – Honolulu, HI