Harry Eto, promoted to eighth degree black belt in 1998 at the age of 92, was one of Koichi Tohei’s first students in Hawaii. Here is a section of the article that appeared in the local Honolulu Advertiser newspaper when he passed away in 2001:

Harry Setsuo Eto, a barefoot Kaua’i plantation boy who literally helped build Honolulu and at middle age became a world-renowned martial arts teacher, will be remembered by family, friends, co-workers and students today at 6 p.m. Honpa Hongwanji services in Honolulu.

Harry Eto discovered martial arts at age 47 and became a world-renowned sensei.

Eto, born Aug. 9, 1906, to immigrant parents who found Hawai’i plantation life even harder than the life they left behind in Kumamoto prefecture, Japan, died June 26 in Kuakini Hospital after suffering a series of strokes. He was 94.

His life was a lesson, and Harry Eto was student and sensei alike.

“Physically I am nothing,” the 5-foot-3, 120-pound aikido teacher said in 1995. “I don’t have any strength.”

But he routinely swept the mats of the dojo at Central YMCA and across the United States with men twice his weight. His advice was: “If your opponent wants to hit you, say, ‘Thank you, please hit my head,’ then step out of the way and help him down.”

Furyu: The Budo Journal, Issue Number 1

Furyu: The Budo Journal, Issue Number 1

The late martial arts magazine “Furyu: The Budo Journal” was established in Honolulu Hawaii in 1994 by local Budo instructor Wayne Muramoto. In addition to modern seitei iaido and classical Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu iaido he is also an instructor Bitchu-den Takeuchi Ryu.

The following article on local Hawaii Aikido instructor Harry Eto first appeared in issue number one of “Furyu: The Budo Journal” and is reprinted here with the permission of Wayne Muromoto. You may also be interested in “Flow Like a River: Takashi Nonaka and the Hilo Ki-Aikido Club“, which appeared in Furyu magazine issue 4.

Aikido’s Harry Eto: The Wisdom of ‘Slow and Steady’

(from “Furyu: The Budo Journal”, issue number 1, reprinted with the permission of Wayne Muramoto)

“I don’t have any strength,” Harry Eto proclaims. And you have to believe him. Dripping wet, he barely weighs 120 pounds, stands a little under five feet three inches, and is well into 87 years of age. But when he steps on the mats to teach Shin Shin Toitsu aikido, energy flows out of him from somewhere, and suddenly the grandfatherly little man becomes a graceful, powerful aikido sensei.

He leads an uke partner at least twice as young and twice as heavy through a movement, throwing him halfway across the mat.

“. . . I rely on my ki; I’m relaxed. I go along with them. (In aikido) we learn how to get along together, with non-fighting mind,” Eto explains. And watching him move, you have to believe him. There’s something more to his aikido than sheer physical strength or technical mastery. There’s inspiration. And the skill that comes from forty years of study.

Harry Eto was born and raised on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, in Lihue. After attending Hanamaulu Elementary, the son of immigrant Japanese parents had to go to work in the sugar cane fields to help the family survive. He recalls running into the cane fields to hide and cry to himself because he couldn’t go on to further his education. Instead, he had to work for a dollar a day at the age of 14. At the age of 16, Eto became a carpenter’s apprentice, then at 17 he moved to Honolulu, on the island of Oahu, and attended night school in carpentry while he worked full-time as a carpenter’s assistant, eventually becoming a full-fledged carpenter.

Eto makes a point at the dojo located at the Honolulu Central YMCA, near the Ala Moana Center. Behind him is a portrait of Tohei sensei and a calligraphy of the character ki from aikido.

“I had no more time to fool around,” Eto says, letting out one of his frequent giggles.

Eto, night school diploma in hand, moved on, becoming an estimator, foreman, superintendent. His work helped support his wife, Lillian Kiyoka, and a family of four girls up in Alewa Heights, in Honolulu. At the age of 70, he retired from Pan Pacific Construction, Inc., but was asked to come back as a part-time safety officer. In that capacity, Eto worked up until last December, when he finally fully retired, after 73 years of working in the construction industry. He is presently devoting his energies to teaching aikido.

Training in aikido helped Eto to relax on the job, he claims. “It taught me to get along with the boys. We work together and I get production out of them. That’s human relationships, to get along. I talk to them about safety, keeping a cool head, not fighting.”

Eto is proud to say that since starting aikido, he didn’t encounter one fight he was involved in on rough and burly construction sites.

“People ask me, do I use my art? I say no. I used my art to separate fights (twice), not to fight. And the workers all respect you.”

Ki training also helped him solve problems at work. When you hit a snag, Eto says, “You can’t help it, so there’s no sense worrying. When I had a heart attack, I felt if I go, I go. If you worry, you can’t think. Forget worry, that’s the easiest way.”

The seventh-dan Eto has been training in aikido for forty years, being among the first students in America to study the new martial art when Tohei Koichi sojourned from Japan under the aegis of Ueshiba Morihei. Eto still remembers that eventful year of 1953.

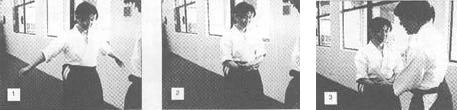

Eto Sensei tests Shannon Fujiwara’s “standing with mind and body coordination.” Student Roy Uyehara looks on.

“Friends told me of a kind of martial art where you don’t have to use strength. (Tohei sensei) was throwing all the judo boys down.”

Curious, the 47-year-old Eto went to see what it was all about. He watched a demonstration at Kawananakoa Intermediate School. He had previously only “fooled around” at boxing, and had no other real martial arts training.

“When I saw the demonstration, I thought it was kind of peculiar. . . But at the time, I didn’t want to learn how to throw (anybody). I wanted to learn for my health because I was underweight, with a weak body. I thought I could regain my health.”

Eto, who weighed only 105 pounds at the time, was one of the oldest students-and the slowest, according to him. “There were all the young boys and judo instructors. Then I had to learn how to take a fall. I had a hard time in the beginning. So I struggled then because I didn’t come to learn martial arts. . . Tohei sensei used to scold me, ‘Ey, how come you’re too slow?’”

But Eto kept at it, attaining his black belt ranking after three years.

“Most of my age group quit. I’m practically the only one left over. . . Instead of quitting, I kept on going. I enjoy it because I felt all these years of good health.”

Actually, Eto had some major health problems, but he feels that he managed to live through them because of his aikido training.

In 1961, Eto had a heart attack instigated, he thinks, by a bad diet of lots of fatty and salty food. He ended up in the hospital for nine months. Tohei sensei wrote to Eto, asking him to continue his breathing exercises and ki meditations.

Just before he was released, doctors found a tiny spot in Eto’s lungs which they suspected to be tuberculosis. He had to stay in Leahi Hospital for observation and treatment.

While at Leahi, Eto heard of a group of aikido masters visiting from Japan. He arranged to have them give a demonstration to the healthier patients at the sanitarium. Unbeknownst to the doctors and nurses, Eto had also planned a surprise. At the end of the demonstration, he came out dressed in hospital issue clothes and performed tanto-tori (taking away a knife) techniques with the aikido group.

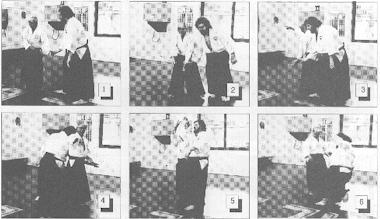

Tekubi kosa: Linda Sasaki practices an exercise called “tekubi kosa.” She swings her arms out and then across each other, palms up, all the while maintaining her “one point.” Another instructor tests her concentration in Photo 3.

“The nurses had their mouths open, they didn’t know what to do!” Eto laughs at the memory.

After his treatment, Eto continued his training. In 1991, Eto had major bypass surgery at the Queen’s Medical Center. He can show a long scar down the center of his chest and along his left leg, where they took out some blood vessels on the inside of his leg to replace some leading to his heart. He credits the skill of his doctors and the teachings of Shin Shin Toitsu Aikido.

“Thanks to ki training, I stayed in the hospital only four days. I was the oldest of five patients who had the operation (at the same time), but the first one to go home.”

Eto sees a lot of benefits from aikido after looking at it from his decades of experience.

“Aikido is not only aikido. Shin Shin Toitsu (the style of aikido taught by Tohei sensei) is mind and body. I don’t have any strength, so I rely on my ki, relaxed. I’ll go along with them. We learn how to get along together, with non-fighting mind.”

The concepts of Shin Shin Toitsu, Eto says, are encapsulated in four principles:

- Keep one point.

- Relax completely.

- Keep weight underside.

- Extend ki.

“You have to follow the principles or we’re lost. But we must practice what we preach, otherwise it wouldn’t work. . . For me to teach class is easy. . . I cannot use strength. (But) with our training, I don’t have to struggle.”

For Eto, the proof is in the pudding. Still barely tipping the scales at 120 pounds, he gives up years of youth, weight, strength and height to his students.

He manages to sweep the mats with them by trying to maintain the four principals within his own spirit first.

“If I cannot clean my own house, I cannot teach you how to clean up your house. The mind and body have to become one. They cannot be separate. When your partner is coming, you go along in the same direction. I become one and we go together. I just lead him, we don’t throw.”

Eto sensei demonstrates a technique called “katate tori tenkan kokyunage” with black belt Bob Wilders. When Wilders grabs his left wrist (1), Eto turns and leads Wilders around his “one point,” then he shifts direction and seemingly without effort throws him.

Eto serves as chief instructor with the Aloha Ki Society, which has branches in Kaneohe, Kailua, Noelani, Waipahu, Wahiawa, Lanakila and the Central YMCA on Oahu. He teaches twice a week, at the Central YMCA and on the weekdays at the different dojo. The organization has close to 200 students enrolled, including men, women and children. Eto believes he is the oldest active member of Tohei’s Ki Society.

“Thanks to my ki training, I’m able to enjoy my life in good health. At 87 I’m still continuing,” Eto reflects. “The body becomes weak, but mentally I’m getting stronger, thanks to ki training.” But then he pauses and credits his happiness in martial arts to another vital component.

“Without them (the students) I’m nowhere. We work together, friendly. So if I get mad with my students, I cannot teach. Without them I’m nothing because I got nobody to teach.

“I’m not going to give up practice. When I stop, I’m dead already. If I can’t teach, that means I’m a vegetable, I cannot do anything. As long as I have my mind clear I’m alright, because the mind controls the body.”

Copyright ©Tengu Press and Wayne Muromoto. All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply