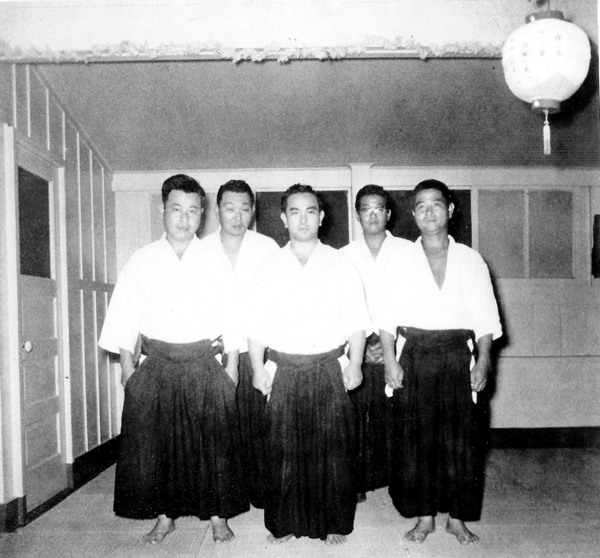

Takashi Nonaka, Yasu Iwasa, Koichi Tohei, Kazuo Takaki, Kiyoshi Nagata

1955 – Hilo, Hawaii at the teahouse in Liliokulani Park

(Photo courtesy of Dr. Mitsuo Adachi Sensei – orginal photo by Bernie Lau)

The oldest of eight children (three boys and four girls), Takashi Nonaka was born on the Big Island of Hawaii on May 8, 1925, he was the oldest of eight children.

His father, Satoru Nonaka, was bon in Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan. Since his parents and grandparents spoke only Japanese he learned to speak the language fluently, and was the translator for Morihei Ueshiba O-Sensei during the Founder’s seven day visit to Hilo. At that time he was a second degree black belt, and the head instructor of the Hilo Aiki Dojo. At the time of this writing he is an 8th dan in the Hawaii Ki Federation and still instructs at the Hilo Shin Shin Toitsu Aikido dojo. Founded in 1955 it is one of the oldest dojo outside of Japan.

Furyu: The Budo Journal, issue number 4

Furyu: The Budo Journal, issue number 4

The magazine”Furyu: The Budo Journal” was established on Oahu in 1994 by local Budo instructor Wayne Muramoto. In addition to modern seitei iaido and classical Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu iaido he also teaches Bitchu-den Takeuchi Ryu in Honolulu.

The following article on local Hawaii Aikido instructor Takashi Nonaka first appeared in issue number four of “Furyu: The Budo Journal” and is reprinted here with the permission of Wayne Muromoto. You may also be interested in “Aikido’s Harry Eto: The Wisdom of ‘Slow and Steady’“, which appeared in Furyu magazine issue number 1.

Nonaka (standing, right) and members of the

Sunday morning class of the Hilo Ki-Aikido Club.

Flow Like a River: Takashi Nonaka and the Hilo Ki-Aikido Club

(from “Furyu: The Budo Journal”, issue number 4, reprinted with the permission of Wayne Muramoto)

Takashi Nonaka was stymied. He didn’t understand most of what O-sensei, the founder of aikido, had said in his speech to the assembled audience, who waited with bated breath to hear Nonaka’s translation. After the usual welcome remarks, the white-bearded Ueshiba Morihei had launched into a rambling discourse concerning esoteric Shinto. “100,000,000 years ago, there were the elements of fire and water. . .” O-sensei said. It got even more perplexing after that.

Translating O-sensei’s “Good evening and thank you for inviting me to Hawaii,” was simple enough. But to Nonaka, who could speak and read Japanese, everything else was mysterious and strange. Taking a deep breath, Nonaka decided that the best strategy was to be honest. He admitted to the audience that he didn’t understand what O-sensei was saying.

“. . .And if I come of his age, I hope I become wise enough to understand what he said today,” Nonaka humbly concluded. The audience clapped loudly and Ueshiba, who didn’t understand a word of English, beamed happily.

Even when Nonaka was later called upon to translate before an audience with a Buddhist minister who spoke perfect Japanese, he felt that honesty was the best policy and admitted his ignorance of the esoteric concepts that O-sensei was talking about. Later at that banquet, he stepped up to the minister and apologized in Japanese. “I’m sorry but my Japanese was too poor. I couldn’t understand what O-sensei was saying.”

The minister laughed. “Me too!” he said.

The story gets even funnier. When O-sensei returned to Japan, he called all of his top-ranking deshi (students) together. They thought he would be in a good mood. After all, he had just returned from a very eventful trip to Hawaii, a successful trip that O-sensei made to United States soil. But what they got was a dressing-down.

“What’s the matter with all of you?” O-sensei stormed. “You never understand what jiji (the old man; an informal term O-sensei used for himself) is saying. But Nonaka-san in Hawaii understood everything clearly!”

Chastised, the students wondered who the heck was this Nonaka-san? Surely he must be a wise old intellectual, to understand O-sensei’s long, rambling discourses on esoteric Shinto concepts. Thus, when Nonaka visited Japan, O-sensei’s senior students made perplexing comments to him like, “I imagined you would have been older!”

Tohei sensei, Nonaka’s main teacher, knew what had happened and thought it was hilarious. Nonaka himself still laughs at this cross-cultural mixup, one of many humorous and memorable events in his long career in aikido.

Originally, the 70-year-old Nonaka was a kendo enthusiast growing up in Hakalau, just outside of Hilo town on the Big Island of Hawaii. At 16, he was among the last of the prewar shodan (first rank “black belt”). At that time, Nonaka recalls, “Kendo was stronger than judo. We used the old Hilo High School gym and took the (shodan) test in July (1941). So our names didn’t go to Japan and the (Japan) Kendo Renmei (organization).” Thus, when Pearl Harbor was bombed and war started, Nonaka wasn’t detained by the FBI, which had secured a list of all ranking budo experts in the Islands.

The first Japanese budo to be allowed to be openly practiced at the end of the war was judo, so Nonaka joined a judo club at Honomu to keep active in martial arts, but stopped when he got married and became involved with domestic life and his work.

Nonaka sensei first started aikido in 1955, two years after Tohei Koichi first came to Hawaii to proselytize the new art. Tohei sensei had returned to Hawaii to teach and give seminars and demonstrations. “I was impressed with what he had to say, “Nonaka recalls. “I signed up that same night.”

There followed years of training in aikido, way back when it was seeking to find its own niche in Japan and the West, to when Tohei decided to create his own organization, the Ki No Kenkyukai, to the present consolidation of the aikido world into various stable organizations.

Being a former judoka, Nonaka could take the falls, and so Tohei used him a lot as uke when he taught on the Big Island. It might have been somewhat of an honor, except that Nonaka was a rank beginner in aikido and didn’t know what was going to happen whenever Tohei gestured to grab him. Tohei-sensei would point to his lapel or sleeves, with one or two hands. Okay, Nonaka would figure out that meant grab him with one or two hands. So he did. And then he’d be flying through the air.

This was, after all, when aikido was still a mysterious art and no one in Hawaii knew much about its methods or its mysterious techniques. Nonaka considers himself fortunate, however, to have been with Tohei when the master was a vigorous 32-year-old, and to have opened his home to Tohei and O-sensei, because he was able to have long discussions through the years with them about the spiritual and philosophical meaning of aikido.

“I could see the change, the development of ki principal (under Tohei),” Nonaka recalls. “At first he was only teaching technique. But over the years, I could see the change. Tohei sensei saw that the way of training in Japan wasn’t sufficient. He had a hard time throwing 250-lb. (American) police officers. He went back (to Japan), started thinking about ki. . .

“Ueshiba sensei could do all the waza, he could do ki, but he was way above in the clouds. Ueshiba sensei was hard to understand,” Nonaka muses. When he told Tohei that he couldn’t grasp O-sensei’s philosophy, “Tohei sensei told me, instead of trying to listen, watch his movements.”

What turned the corner for Tohei, Nonaka feels, was meeting a modern-day Japanese mystic, Nakamura Tempu. Famous in Japanese esoteric circles, Tempu is all but unknown in the Western budo world, but his impact on Tohei and Ki No Kenkyukai is immeasurable.

Nakamura Tempu had studied yoga and other esoteric philosophies in India and established the Tempukai, an organization based on Hindu mysticism. The central point in his system was the development of breath (prana in Hindu), which led to the strengthening of ki. Tohei connected Tempu’s concepts and training system with the aikido he had learned from O-sensei and realized that there was a strong similarity between the two, and that teaching ki based on some of Tempu’s ideas was a way for people to understand what O-sensei was trying to teach.

“What Tohei was trying to teach was the principal of ki. Ki is like a radio beam, you can direct it,” Nonaka says. “Therefore, Tohei sensei’s teachings is the waza from Ueshiba O-sensei and the mind part form Tempu. He put it together.”

In properly executing aikido movements, you should be creating the ki no nagare, the “flow of ki,” which Tohei explained to Nonaka was “Like a river, the flow of water. So there is no sharp angle in the river. It makes a nice curve. So we train not to cut the ki.”

Nonaka leads a class in aikiken practice

at the Waiakea Rec Center in Hilo, Hawaii.

Nonaka, who was a manager at an agricultural soil and plant tissue analysis control lab at C. Brewer, retired in 1986. Nonaka and his wife, Toyomi, have two children. Their daughter, Anne Gorden, lives and works in West Covina, Los Angeles, and his son Eric (a fifth dan) lives on Oahu, where he is the instructor of the Mililani Hongwanji Ki-Aikido club. Nonaka is proud of Eric’s aikido accomplishments.

Just before graduating from college in 1976, Eric was accepted as one of Tohei’s uchi deshi (live-in student) for six months, and received his sandan ranking directly from Tohei. Being an American and the biggest of Tohei’s uchi deshi, Eric was dragged all over the place to help with demonstrations, since it was impressive to see the strapping, 200-lb. young Eric being bounced around by Tohei only with the power of ki. “He (Tohei) took him as otomo (second) because he looked impressive. So Eric learned a lot from watching his demonstrations.”

Presently, Nonaka is a seventh dan with the Ki No Kenkyukai and serves as chief instructor for the Big Island, with Roy Yonemori as the head of the Hilo Ki-Aikido Club. The club meets at the Waiakea Recreation Center in Hilo town, with instructor classes on Sunday mornings and regular and children’s classes almost every day of the week.

Nonaka has visited Australia, New Zealand and Singapore to give seminars in ki and aikido. In doing so, he realized that his bilingual abilities were a plus in his aikido training and teaching, even though he fought against his parents as a child when they insisted he study Japanese. “Now I appreciate the fact that my father was strict in having me learn Japanese.”

Not only could Nonaka understand the deeper philosophical and technical side of aikido by understanding his Japanese teachers, but he could also impart that knowledge to English-speaking aikidoka. That, he found, was one factor that was appreciated by his hosts Down Under in Australia, New Zealand and Singapore.

“When Japanese instructors teach, they teach a lot of waza (because of the language barrier). But Tohei spent time explaining the philosophy and processes to me.”

What Nonaka values most from his decades of aikido training is also the fact that “What we learn is applicable and should be applied to daily life. To me that’s more challenging than polishing my waza to throw somebody. At may age, I’m not interested so much in the throwing part.”

What he learned in a nutshell was, “To learn to relax your subconscious mind and have positive thinking (attitude). . . It’s a people-to-people relationship. I could apply that philosophy to management. I managed a lab for 35 years and never had a need to fire anybody. We had expensive equipment. I always assigned the proper person to the proper assignment.”

In addition, Nonaka was elated that his cardiologist recommended his patients to take up ki training to learn how to relax. And after speaking to mental health officials, a psychiatrist began to send some of his patients to his classes. Basically, Nonaka says, “A lot of them (patients) needed to change their negative thinking. The difference between negative (thinking) and positive is paper thin. But when you train together, the whole atmosphere is positive, so you cannot have a negative attitude, so slowly you change the negative attitude to positive.”

After listing some other examples of how ki and aikido helped various individuals, Nonaka concludes, “I’m happy to be able to help the community. I’m not interested in teaching 50 young kids to throw somebody.”

Nonaka’s training, however, was sorely tested two years ago, when he had knee surgery on both his knees at the same time due to severe arthritis. He had a successful total knee cartilage replacement, although he was warned not to jump, twist or over-bend. That has precluded him from doing a lot of aikido in seiza, but not much else. Nonaka continues to busy himself with a full teaching schedule.

On reflection, Nonaka says that in spite of his aikido training, he felt depressed after the surgery. Then he went to the therapy room at Queen’s Hospital on Oahu and saw people a lot worse off than he was. “Compared to them, I’m pretty good,” Nonaka realized. “Right there, by changing my thinking, I changed to positive. If the doctor wanted me to do an exercise fifty times, I did a hundred. So the therapist said I was 1 1/2 months ahead of normal progress!”

Nonaka uses this exercise to develop unity of mind, body and ki. He places his bokken lightly atop that of Jim Fordham. Then he concentrates and pushes down the firmly (but not rigidly) held bokken of his partner by an exhalation of breath, sinking of hips, and ki focus, all in one instant.

Nonaka analyzes the process of a throw and says, “Before you throw somebody or perform a waza, you should:

- relax and extend your ki

- respect your opponent’s power

- find out which way his ki is going

- put yourself in your opponent’s position (or frame of mind);

- and then execute with confidence.

“You can do that in daily life, dealing with people,” Nonaka says. “When people argue louder and louder, they don’t want to hear the other person’s voice. . . But try to respect what people can do. Then what direction is his mind going? What is he really talking about? Then try to see his direction, his position, step by step. Put yourself in the person’s position, try to understand his point of view. Then lead him. Therefore he doesn’t mind listening to you.”

Nonaka feels that this advice is so persuasive because it has universal appeal. “That philosophy is the same as the late Dale Carnegie’s in his book How to Win Friends and Influence People. I read that book three to four times! The more I read it, the more I think it’s the same philosophy that Tohei is trying to pass on to us.”

And although he claims to not understanding the gist of O-sensei’s talks, Nonaka was privy to a private lesson and some individual conversations with the elder Ueshiba that opened his eyes to the spiritual aspect of aikido. Between Tohei’s clear concepts and Ueshiba’s cryptic sayings, Nonaka realized that aikido went beyond mere physical throwing and pinning people.

Once, O-sensei visited Nonaka’s home in 1960 and wandered through the orchid garden. It reminded him of his former home in Hokkaido, he said, and then, reflective, he told Nonaka, “Life is like a flowing river. Human beings are in the river. Some are going with the current. Some people swim nicely and others are struggling. He (Ueshiba) would like to help the struggling people, but won’t jump into to river. He stays on the river bank and throws in ropes and runs up and down the river (to see if there’s a waterfall up ahead). If he’s in the water with them, he might get caught and can’t see the waterfall. At that time, I didn’t understand it,” Nonaka says. Gradually, however, he feels he is beginning to comprehend O-sensei’s symbolisms.

At another time, in 1968 in Tokyo, Nonaka, his son, and his wife had a private audience with O-sensei, and he took that opportunity to ask some pointed questions about aikido.

Why is there no shiai (contests) in aikido?

O-sensei said, “If there’s shiai, there’s always a loser. He’s not happy, so he’ll get back at you later. So instead of beating a person, winning over yourself (your ego) is harder. So you do keiko shugyo (austere training).”

Nonaka also asked, “In Doshu’s book (on aikido), he says something about enjoying practice, doing keiko with joy. . .”

O-sensei nodded in agreement. “When you learn something enjoyably, you grasp more instead of when suffering. If you intend to help a student, take uke (the one being thrown). . . Uke wa sensei da (the uke is the teacher). Give students a chance to relax, then you move.”

That lesson reminds Nonaka of a saying of Tohei’s:

There are three ways to win over someone:

- by brute force, but the person will never forget that and will get back at you.

- by intelligence. You trick him. Say you dig a hole so that when he attacks, he falls into the hole. But he still won’t forget and you can’t trick him twice.

- by winning the person over by showing him respect. . . But you must show respect first and earn respect from the other side. That’s true victory, and it must come from the heart.

That magnanimous spirit is what Tohei calls intoku, which is akin to the Buddhist and Christian ideal of unconditional love or compassion.

“So marriage is not 50/50. It’s 100%-100%. You give 100% and your wife gives 100%, and so two sides are totaling 200%. I’ve got to keep reminding myself of that! I have to practice what I preach!” Nonaka admits sheepishly.

Still, although retired and favoring his knees, it doesn’t look like Nonaka is going to let up on training. “When I go to a new dojo, I thank the people because I’m sharing my experiences, but I’m also learning how to put it across. So those folks are my teachers. If I can be of help, that’s the best way I can return Tohei sensei’s favors. What I learned from him, I can pass on to others.”

Copyright ©Tengu Press and Wayne Muromoto. All rights reserved.

Remembering Nonaka’s Sensei’s visit to Australia some years back…good times!